Colorado is a state dominated by the Continental Divide. It is also the state where the Divide has been severely altered. Most of its water, provided by snowmelt, spills into the western side of the Divide, while most of the population is on the eastern side. This imbalance has led to water diversion projects that move water from one side of the Divide to the other, that date back more than a century, and include some of the largest tunneling projects in the country. Some of the biggest mines in the nation have re-contoured the Divide directly. Road and rail tunnels undermine the Divide as well. In many ways Colorado is where the Continental Divide ceases to exist.

Entering the top of Colorado from Wyoming—moving from one rectangular state to another—the Continental Divide stays above 10,000 feet, and passes through mountaintops exceeding 12,000 feet, until dropping to 9,426 feet at Rabbit Ears Pass. The pass has the northernmost east/west highway in the state, US Highway 40. To the west is Steamboat Springs, and to the east is Rocky Mountain National Park.

The pass has the northernmost east/west highway in the state, US Highway 40. To the west is Steamboat Springs, and to the east is Rocky Mountain National Park.

Rabbit Ears Pass gets its name from a nearby rock formation, named Rabbit Ears Peak by early trappers.

As with rabbit’s ears, there are two Rabbit Ears Passes. A mile north of the current highway pass is an earlier road, improved in 1919, with a monument noting its passage over the Divide, at 9,680 feet.

After a mile down its eastern slope, the pavement ends where the road is barricaded with a dirt mound, as it is now closed to traffic.

A few miles east of Rabbit Ears Pass, Highway 40 meets Highway 14, where the road crosses the Continental Divide again. The pass is called Muddy Pass, but it is unmarked.

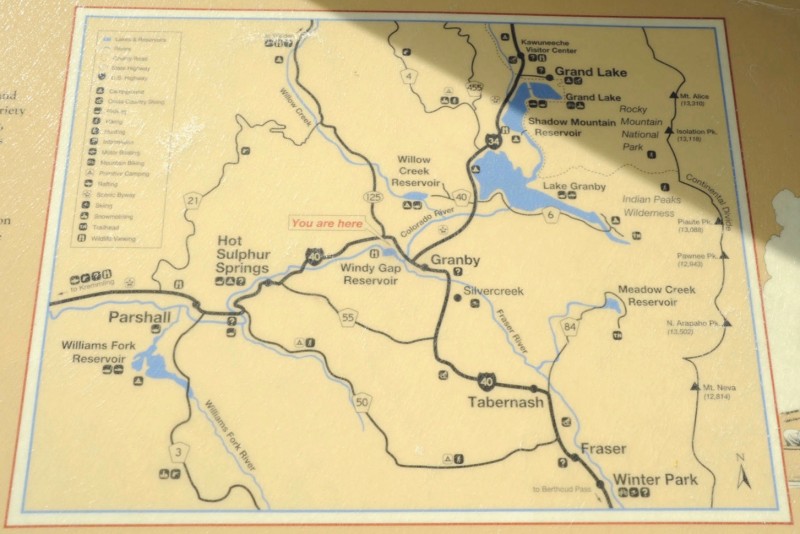

Willow Creek Pass is a pass in the Continental Divide, on US Highway 125, west of Rocky Mountain National Park, connecting the towns of Walden and Granby. It is one of 15 paved highways or roads that pass over the Continental Divide in Colorado.

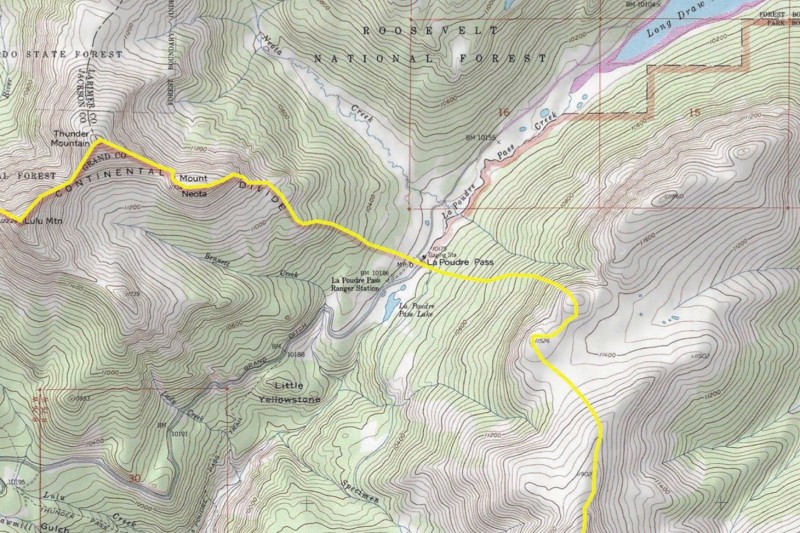

La Poudre Pass is a remote area at the northwest corner of Rocky Mountain National Park, at the dead end of a ten-mile long dirt road from Highway 14.

From the end of the road you can walk in to the park, and there are no rangers here to charge admission.

Though it is unmarked, you pass over the Continental Divide in less than a mile, and arrive at a view looking southwest, over the headwaters of the Colorado River.

There is a small pond there that could be considered the ultimate source of the great river, that drains much of the west slope of the Rockies, and the southwestern USA.

Hikers can observe the pond from a road that runs along the edge of a canal known as the Grand Ditch. A 14-mile long conduit collects water from the western slope, that would otherwise flow into the Colorado River, and moves it to the eastern slope, through the ditch.

The diverted water crosses the divide at La Poudre Pass, then flows into the Long Draw Reservoir. From there it is meted out in a measured fashion, under the dam, into Cache La Poudre Creek, for use on the plains of the eastern slope, around Fort Collins, Thornton, and Greeley.

The Grand Ditch has existed in some form since 1890, but didn’t reach its full length until the 1930s, when the Long Draw Reservoir was constructed. It is owned by the Water Supply and Storage Company of Fort Collins, which had to pay the Park Service $9 million for damages to the environment when the channel collapsed in 2003.

About 20,000 acre-feet of water flows through the ditch annually, an amount estimated as 20-40% of the runoff from its source, the Never Summer Mountains, which the ditch partially wraps around.

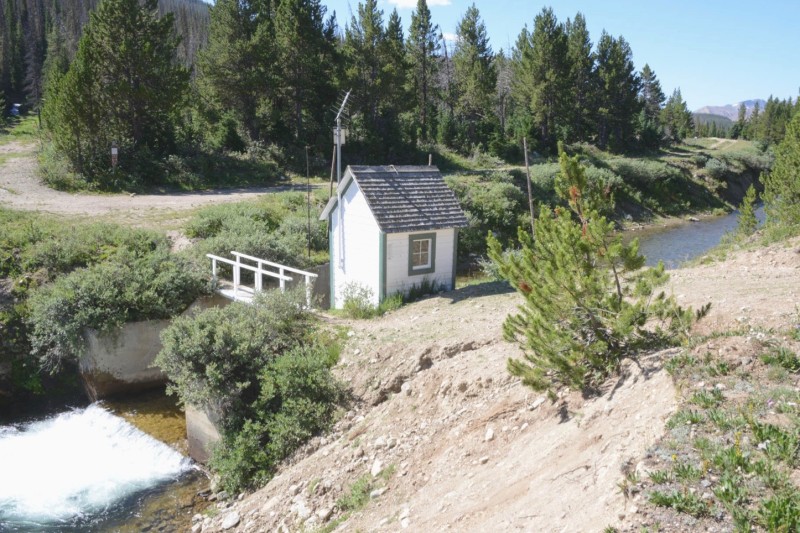

The flow is measured at a gauging station, equipped with telemetry.

According to the USGS, the official federal mapping agency, the Continental Divide crosses the channel just a few feet upstream from the gauging station.

But given the engineering of the hydrologic divide here, their maps may need to be adjusted.

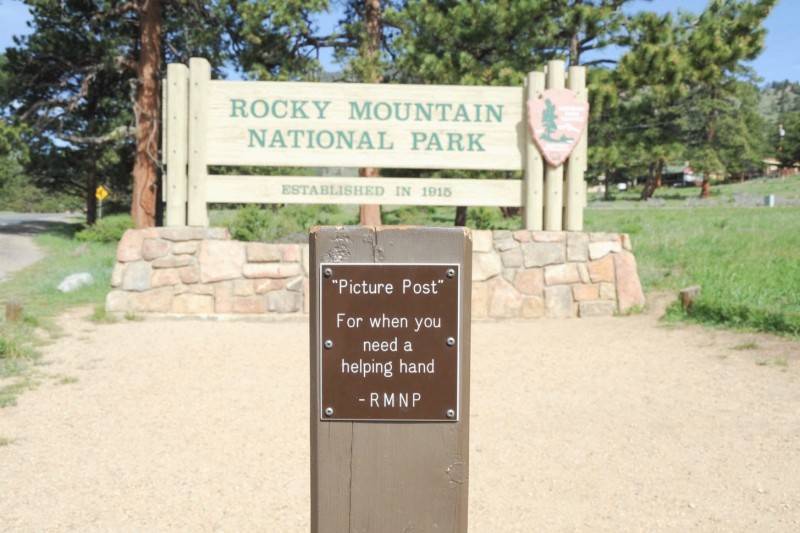

Milner Pass, inside Rocky Mountain National Park, is the next pass south, down the Divide from La Poudre Pass, and though it is just four miles away, it would take hours to drive from one to the other.

Milner is along US Highway 34, known as the Trail Ridge Road, which is the highest paved through-road in the nation.

The Trail Ridge Road reaches a peak of 12,183 feet, a few miles east of Milner Pass.

The road was constructed from 1926 to 1932, and is closed for the winter when it is covered in drifts up to 35 feet deep.

There is a visitor center along the road between the pass and the high point.

The visitor center is at an elevation of 11,796 feet.

The highest paved road in the country, incidentally, dead-ends at a parking lot at the summit of Mount Evans, at 14,130 feet (60 miles south of here, and five miles east of the Continental Divide).

Highway 34 is not the only impressive engineering feat inside Rocky Mountain National Park.

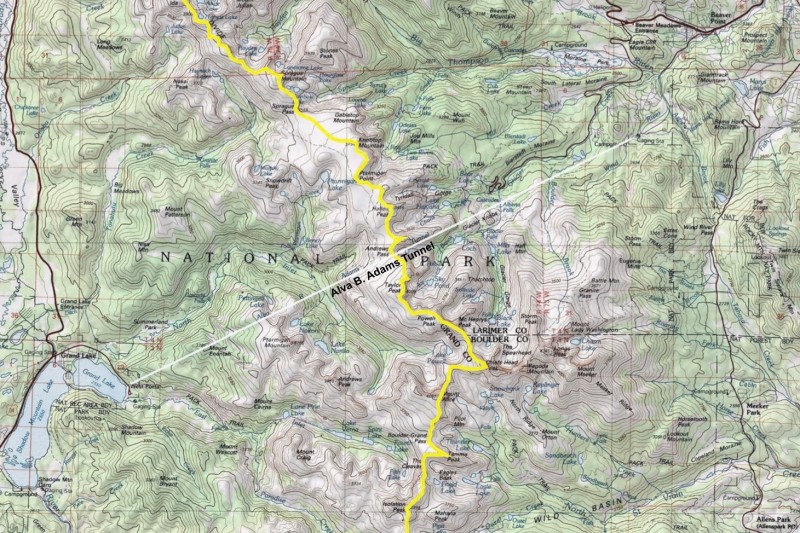

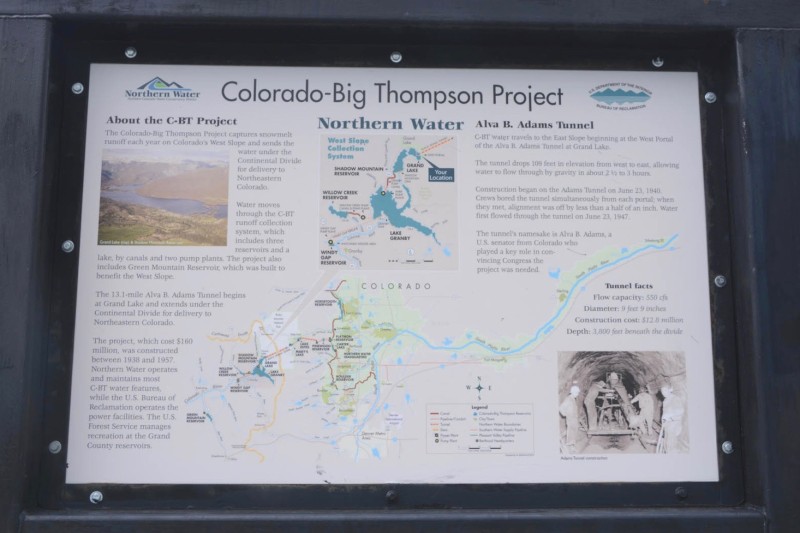

A 13-mile long ten-foot wide water tunnel runs under the park, from one end to the other, crossing 3,700 feet under the Continental Divide near Andrews Pass.

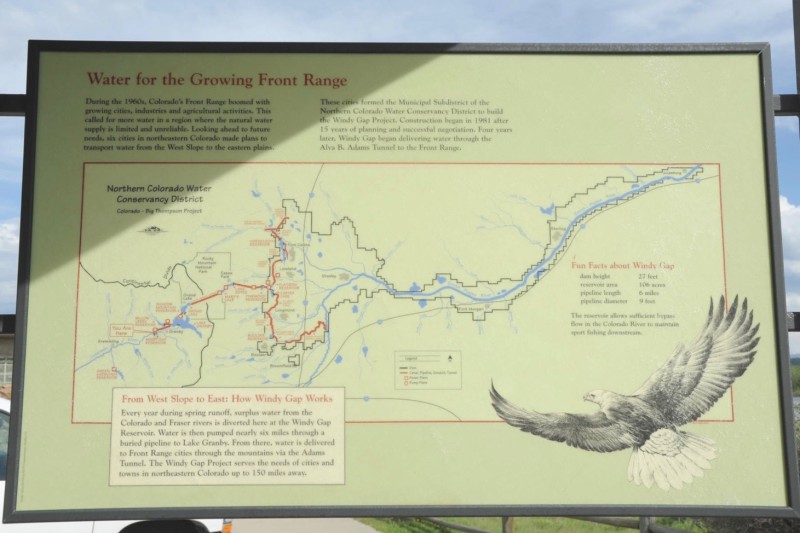

The tunnel is the fulcrum of a network of trans-basin, trans-Divide reservoirs and pipelines known as the Colorado-Big Thompson project, built by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and completed in 1947, at a cost of $160 million.

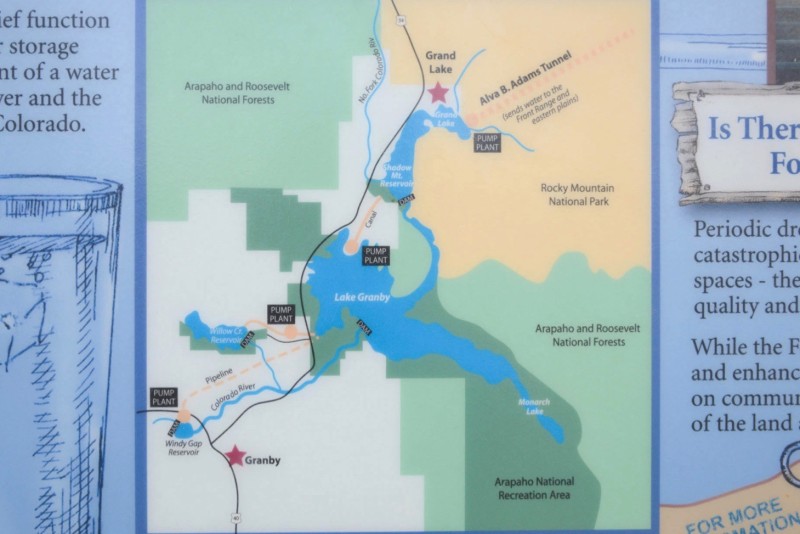

The system involves a number of reservoirs, pipelines, and pumping stations on the western slope, to collect water that would otherwise flow into the Colorado River, and away to places like California.

The Willow Creek Reservoir and the Windy Gap Reservoir deliver captured water to Lake Granby, the largest of the reservoirs in the system, via pipelines and canals.

The Farr pumping station lifts water out of Lake Granby up a hundred feet more in elevation to the next level of reservoirs.

That water then enters the Shadow Mountain Reservoir, via the Green Ridge Gates.

The water flows through a channel between the Shadow Mountain Reservoir and Grand Lake, which is highly developed as a recreational lake.

At the other end of Grand Lake the water is siphoned out of the lake at the western portal of the Alva B. Adams Tunnel, where it flows under the Park, and over the Divide.

Meanwhile, the Colorado River itself flows through the same system of reservoirs, but in the opposite direction. It enters the Shadow Mountain Reservoir as a somewhat wild stream, emerging from its headwaters at La Poudre Pass, 20 miles north.

At the Shadow Mountain Reservoir, its waters become part of a captured hydraulic infrastructure, and a fully controlled resource. It leaves the reservoir in a measured way, out of the Shadow Mountain Dam, and flows into Lake Granby.

The water leaves Lake Granby, also in measured amounts, through a tunnel at the base of the Granby Dam.

It flows for another eight miles to the Windy Gap Reservoir.

Where a pumping station can move water back upslope to Granby Lake, if needed.

The remaining water heads out through the Windy Gap Dam, and onward, downstream, as the Colorado River again. The river meets the engineered embankment of Interstate 70 in about 75 miles, then follows the Interstate to Grand Junction, and into Utah, where it is backed up again as Lake Powell.

Back upstream, at Grand Lake, the collected Colorado River water enters the Adams Tunnel through an underwater tube, under a red buoy.

From there it runs as a straight line for 13.1 miles under Rocky Mountain National Park, to the east portal, which is 109 feet lower in elevation from the west portal, allowing the water to flow by gravity. It gets from one end to the other in around two hours.

The tunnel emerges at the east portal, after crossing 3,700 feet under the Continental Divide, at a small reservoir. When the tunnel opened in 1947, it was the longest irrigation water tunnel in the nation. Today the annual 220,000 acre-feet of water it delivers is consumed by a variety of end users, mostly urban.

As at the western portal, there is a small power station on top of the east portal, where a bit of electricity is generated by the flow.

The water enters a pipeline at the other end of the reservoir, and heads to a string of downstream reservoirs, including Lake Estes, a reservoir in Estes Park, made by damming the Big Thompson River. From there the Colorado River water, now joined with the eastern slope’s Big Thomson River water, flows off to other reservoirs that store water to be used by the booming population in cities north of Denver.

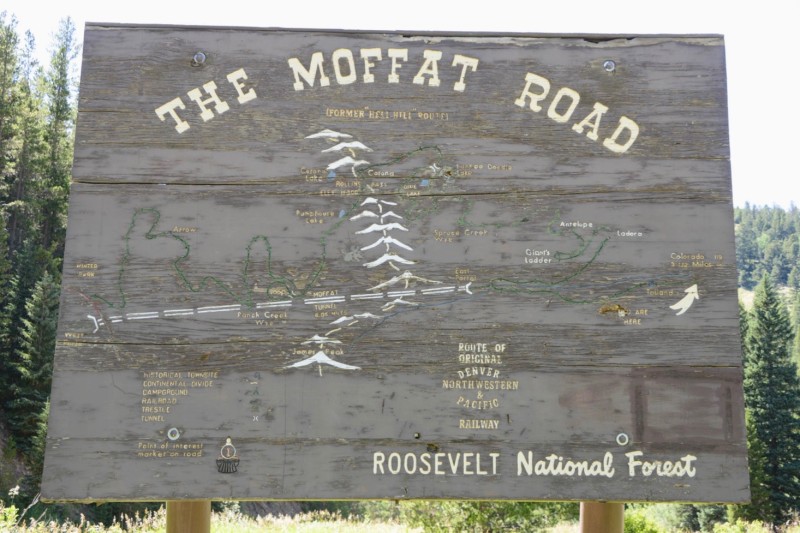

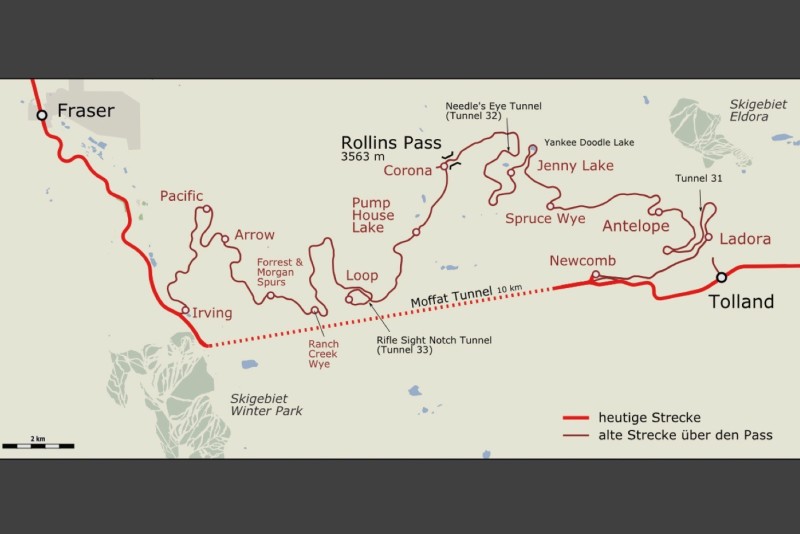

25 miles south down the Divide from the Alva Tunnel is Rollins Pass, where a railroad was built over the Divide starting in 1903. With the pass at 11,677 feet, it was the highest non-cog railway in the nation. Much of the route was covered with wooden snowsheds, but snow removal was always a problem.

Continental Divide

The route over the pass, sometimes called Hell Hill, was part of the Moffat Road, and it was meant to last just until a tunnel could be built at a much lower elevation, away from the snowdrifts, and without all the curves and the 4% grades.

This finally happened in 1928, when the Moffat Tunnel opened, and this 23-mile section over the pass was made obsolete.

The tracks were pulled up around 1936, and over time the trestles and three tunnels on the route collapsed. The 170-foot long Needle’s Eye Tunnel, near the crest of the Pass, remained somewhat intact, and was visited recreationally by motorists, bikers, and hikers.

It was closed off in 1990, after a visitor was injured in a rock fall in the tunnel. Since that time the route has been blocked.

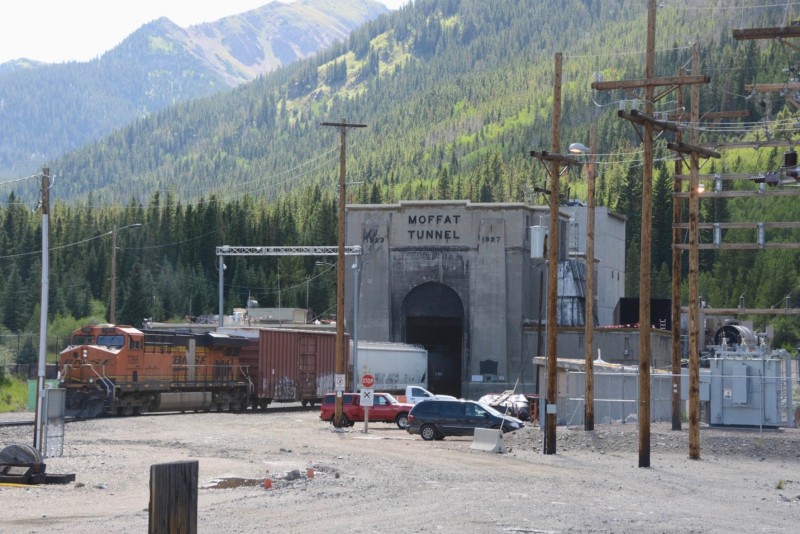

The Moffat Tunnel’s east portal is at the base of the old railway route over Rollins Pass. It is a popular parking spot for hikers, though the railway areas are fenced off from public access.

Work on the Moffat Tunnel started in 1924, and it took four years to drill and blast the 24-foot high and 18-foot wide hole, 6.2 miles though the mountains. It is actively used for freight trains by Union Pacific.

The Moffat Tunnel is the fourth longest mainline railway tunnel in the USA. It goes under the Divide between Rollins Pass and Rogers Pass, 2,440 feet lower than Rollins Pass.

The west portal is at Winter Park, a ski resort, developed by the City of Denver.

A disused overlook above the west portal has plaques and monuments from the 1950s that briefly describe how the tunnel was made.

Another plaque describes how Winter Park is the largest municipal ski development in the nation. It opened in 1939, with its first ski lift, built by the WPA, and grew quickly into a major ski resort, owned by Denver’s parks department until the city sold it to a private company in 2002. A weekend “ski train,” which started in 1940, still connects the slopes to downtown Denver, 65 miles away by train.

Another plaque describes how the “Pioneer Bore,” a ten-foot diameter pilot tunnel that runs parallel and 75 feet south of the main tunnel, has been used as a water supply tunnel for the city of Denver, starting in 1936.

Known as the Moffat Water Tunnel, this water comes through a large system of pipelines and reservoirs that collect water on the west side of the Divide, and deliver it the populous east side, via the Moffat Tunnel.

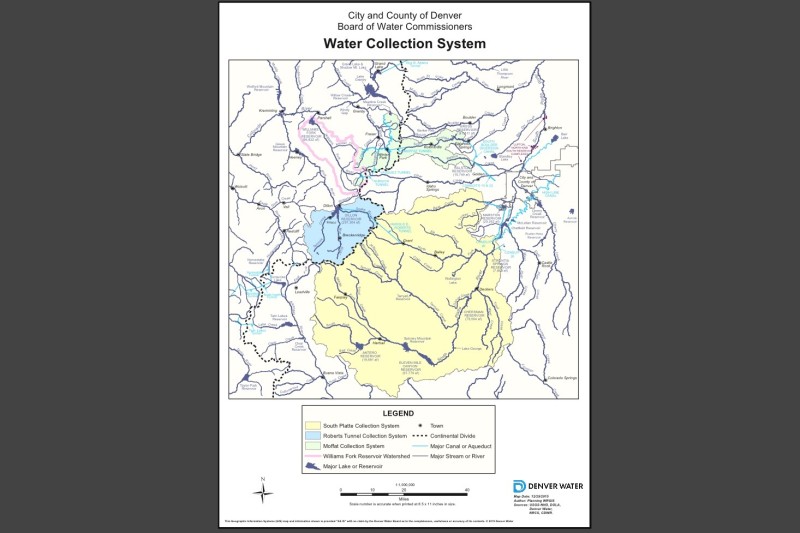

Denver Water, the city’s main water supply company, operates four collection systems to capture water for the city, three of which collect water from the western slope of the Continental Divide, using the watersheds of the Fraser, Williams Fork, and Blue Rivers.

Denver Water’s Moffat Collection System has one lobe on the east side of the Divide, and another on the west side, with the Moffat Tunnel between them. The western side collects water from Fraser River tributaries through a number of aqueducts, tunnels, and existing stream channels.

Each of the two underground tunnels, the Vasquez Tunnel and the Gumlick Tunnel, cross the Continental Divide, bringing water from the Williams Fork River watershed to the Moffat Collection System.

So by the time this water enters the Moffat Water Tunnel, it has crossed the Continental Divide three times, back and forth.

At the east portal of the Moffat Tunnel, the water emerges as a canal that joins Boulder Creek, which flows alongside the tracks for around 15 miles, before spilling into the Gross Reservoir, six miles southwest of Boulder. Efforts are underway to enlarge this reservoir, by raising the dam by more than 100 feet.

The next pass on the Divide, south of the Moffat Tunnel, is Berthoud Pass, which is crossed by Highway 40. A plaque dated 1929 says the pass was discovered and surveyed by Captain E.L. Berthoud in 1861, aided by Jim Bridger. A toll road opened in 1874, and an improved highway opened in 1923.

With an average of 30 feet of snowfall per year, and as much as 60 feet per year, the Colorado Department of Transportation employs a number of methods to minimize avalanche risk at the pass, including automated propane-fueled concussive blast cannons that explode gas in drilled holes, shaking the earth itself to knock down looming snowdrifts.

The pass was best known as a ski attraction, one of the earliest ski hills developed in the state. Before the lifts came, people used their own cars to drop skiers off at the top of the Divide, taking turns to pick them up at the bottom of the run and drive them back up again.

While a private resort near Colorado Springs installed a rope tow in 1936, it’s possible that Berthoud Pass became the first public ski area in the state when it installed one a year later. A lodge was built after World War Two, when the Forest Service issued a permit for the ski hill to operate on their land.

One of the first double chairlifts in the state was installed here in 1947, and lifts operated on both sides of the road, up and down the Divide. The operation continued for five decades, a small but friendly and reasonably priced skiing option, less than 60 miles from Denver.

The ski hill closed in 2002, citing financial reasons, lawsuits, and the expense of improving water collection and sewage treatment facilities. The lifts were taken down in 2003, and the lodge was demolished by the Forest Service in 2005, replaced with a functional warming hut, as the site is still used by self-serve back-country skiers and snowboarders.

There is an electronics telemetry site on the hilltop above the pass, known as the Mines Peak Electronic Site. It has been used as a microwave relay site to convey communications across the nation since 1959, and has a heavily reinforced AT&T microwave relay tower built in the 1970s. There is also weather monitoring equipment at the site.

Also at the pass is the Berthoud Pass Ditch, one of a few dozen trans-basin water collection ditches that move water over the Continental Divide. Originally an irrigation ditch, dating back to 1902, it was purchased by the eastern slope cities of Northglenn and Golden in the 1980s, which each receive approximately half its yield of 500 to 1,000 acre feet per year.

The 3.5-mile long ditch captures water from the headwaters of the Fraser River, on the western slope, then enters the Pass from the north.

It goes underneath the parking lot of the former ski operation, and picks up a bit more parking lot drainage there too.

The water emerges again as a stream from under the southern end of the parking lot, and heads downslope to join the headwaters of the West Fork of Clear Creek, which follows Highway 40 to Interstate 70, and down towards Denver.

The 3.5-mile long Vasquez Tunnel passes invisibly under the Divide near Vasquez Peak, four miles down the Divide from Berthoud Pass. It meets the three-mile long Gumlick Tunnel, which passes invisibly under the Divide near Jones Pass, at a point next to Clear Creek.

The Vasquez and Gumlick Tunnels flow by gravity, with their upstream ends around 100 feet higher than their downstream ends. They are each seven feet in diameter, with a flat bottom.

The meeting point is contained in a small maintenance facility operated by Denver Water. The Gumlick was originally built as the Jones Pass Tunnel in 1940, and drained into Clear Creek. In 1958, when the Vasquez Tunnel was finished, the tunnels were connected here, enabling the water to flow on to the Moffat Tunnel, crossing the Divide for the third and last time.

At 12,454 feet above sea level, Jones Pass is more than 2,000 feet above the Gumlick Tunnel, when it passes under the Divide. The pass usually has snow into August, which does not stop energetic cyclists and hikers.

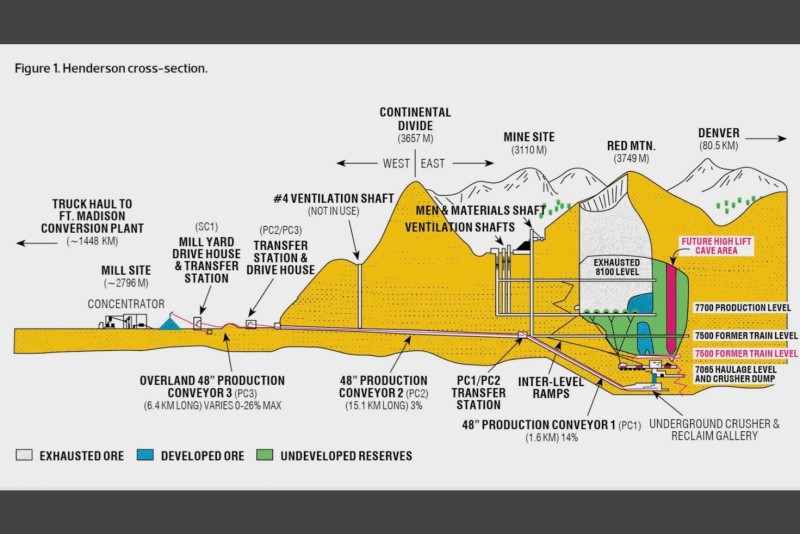

There is another tunnel crossing the Divide invisibly under Jones Pass, too, the Henderson Mine Tunnel.

This tunnel originates at the Henderson Mine, immediately next to the Gumlick/Vasquez tunnel connection point. It is the largest molybdenum mine in the nation, and has produced more than a billion pounds of the material from this site.

At the mine, the rock-bearing ore is blasted out of the living rock, crushed down to soccer ball-sized or smaller chunks, and dumped onto a conveyor belt. This all takes place half a mile underground, with little to see on the surface except huge vents, the elevator headframe, and other support structures.

The conveyor belt enters a tunnel inside the mine that travels under the Divide, then exits next to the Williams Fork River on the western slope, ten miles later. It is the longest conveyor belt tunnel in the country.

The conveyor belt was installed in 2000, replacing an automated railcar system that had operated in the tunnel for a few decades.

The conveyor runs for another five miles from the west portal to the mill, crossing over the Williams Fork River and a dirt road.

The conveyor passes the East Branch Reservoir, which is used as a source of water for the mill.

The mill crushes the rock into powder and uses flotation and other methods to produce concentrated forms of molybdenum. The material is shipped from here to a finishing plant in Iowa, and to other processors, who use it in lubricants and metals.

Waste material from the mill, including tailings—leftover unused parts of the rock—flow in a slurry further downslope from the plant.

The slurry spills into a two-mile long impoundment reservoir.

The Henderson Mine and Mill is one of two major molybdenum operations on the Continental Divide, both of which are operated by Climax Molybdenum, part of the Freeport-McMoRan mining company, based in Phoenix, Arizona.

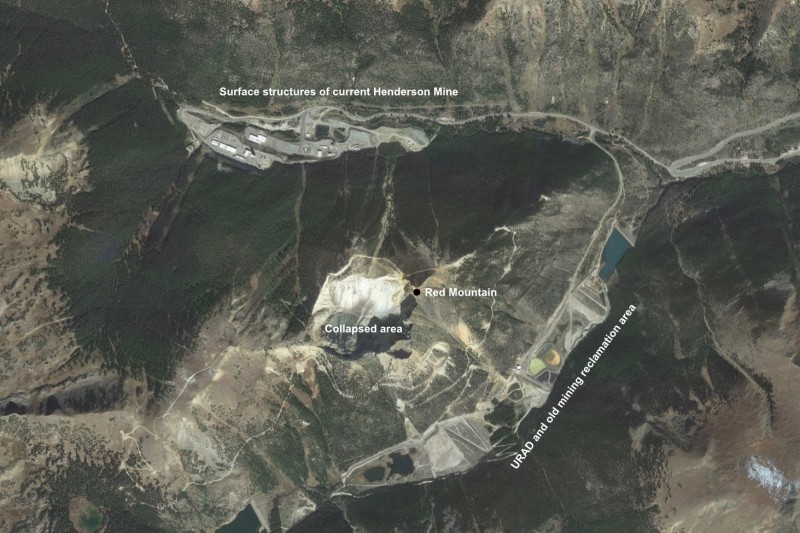

The mine, at the other end of the tunnel from the mill, opened in 1976, expanding deeper into an underground ore body that has been mined for decades before that. In 1980, part of the mine collapsed, sheering off part of Red Mountain, visible behind the surface appurtenances.

The current mine is based out of a pad that is north of Red Mountain, but mines the same underground area as the historic mines, which were based out of the valley on the southeast side of Red Mountain.

The old mining area, referred to as the URAD mine site, closed in 1974, after 48 million pounds of molybdenum were produced by companies that were absorbed into Climax Molybdenum.

URAD became the largest mine reclamation and remediation project in the state, addressing groundwater and other contamination issues. A wastewater treatment plant still operates next to the primary mine portal.

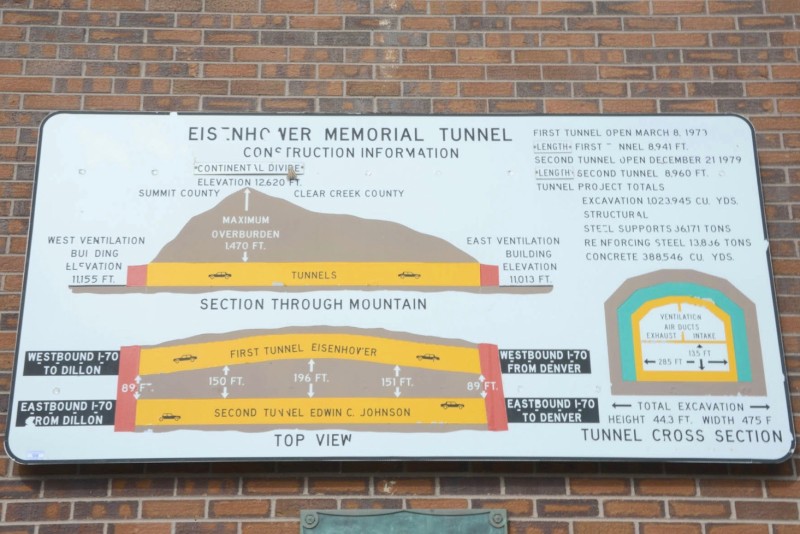

Six miles southbound down the Continental Divide, from the tunnels under Jones Pass, is another set of tunnels through the Divide that are much more visible and familiar to people: The Johnson and Eisenhower Tunnels, which carry Interstate 70 over/under the Divide.

The Eisenhower Tunnel, now the westbound lane, was built first, opening in 1973. Six years later the Johnson Tunnel opened next to it, and the highway was divided.

The tunnels are just under two miles long, and cross 1,470 feet underneath the Divide. At more than 11,000 feet in elevation, it is the highest point on the Interstate Highway System, and they are the highest vehicular tunnels in the nation as well.

The tunnels also carry water over the Continental Divide, from the western slope to the eastern slope. A series of infiltration points collect water from above the western portal into an underground tank, connected to a channel that runs into the tunnel.

The rights to much of this water were claimed, when the tunnels were proposed by the Adolph Coors Company, which sought sources of water for its primary brewery at Golden, on the eastern slope.

The water also joins with surface drainage around the tunnel portals, including from the roadway drains and tunnel seepage.

Some of this water is held for cleaning and firefighting use by the Department of Transportation at the tunnel, but most of it is treated in a treatment plant inside the east portal building, and discharged.

The water flows out of the tunnel into a small pond next to the highway.

Then it joins Clear Creek, a once wild creek, now pushed to the side of Interstate 70, which uses the valley carved by the creek, to get to Denver.

Next to the Interstate is the Loveland Ski Area, one of the closest ski areas to Denver, with chairlifts that approach the Continental Divide above the east portal of the highway tunnel.

The ski area is accessed from the Highway 6 exit off the Interstate. Before the tunnels were bored for the Interstate, traffic on this busy route west of Denver had to cross the Divide on Highway 6, and go over Loveland Pass.

It is one of the highest passes that is kept clear of snow year around by the Department of Transportation, as trucks with hazardous cargo, including gasoline tankers, are not permitted in the tunnels on Interstate 70, and have to take this curvy loop between the west and east portals of the Eisenhower-Johnson tunnels.

The pass also offers convenient access to the snowy Divide, more than two miles above sea level, with back country skiing most months of the year, and less then an hour from Denver.

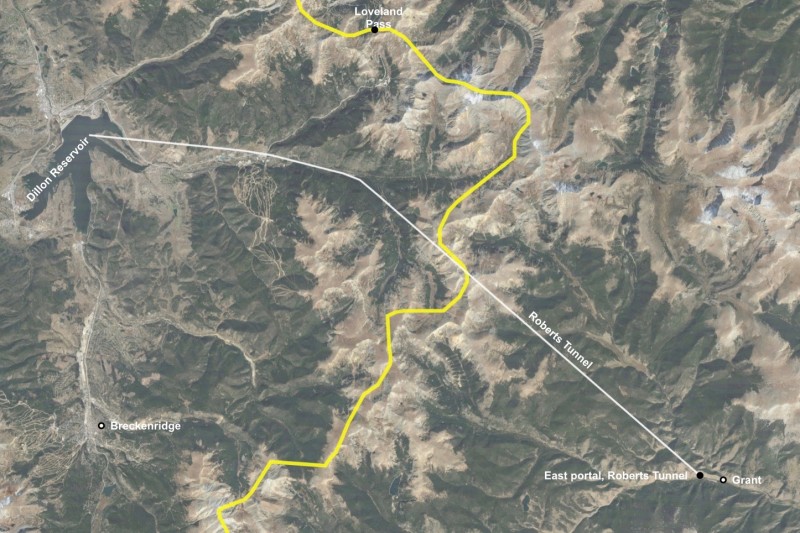

The next major crossing of the Continental Divide is ten miles south, near Santa Fe Peak. This crossing is another tunnel, the Roberts Tunnel, one of the largest and longest water tunnels in the world, crossing more than 4,000 feet below the top of the Divide.

In the 1950s, Denver Water captured Blue River watershed, which flows out of the former mining town of Breckenridge, and built the Dillon Reservoir and Roberts Tunnel to deliver it to Denver.

Construction started in the 1950s, before agreements were even reached. The reservoir began filling in 1963, after the town of Dillon was moved.

The Dillon Reservoir is the largest reservoir for the City of Denver.

The ten-foot diameter Roberts Tunnel begins at its west portal, underwater in the reservoir, controlled by a valve facility on a peninsula. It then runs for 23.3 miles in a straight line to its east portal, near the town of Grant.

The bored tunnel, with an exterior diameter of nearly 16 feet, flows by gravity. At its east portal, 175 feet lower in elevation than its west portal, it emerges from underground just below the grade of the adjacent highway, with a small control building on top of it.

It crosses under the highway, and spills into the North Fork of the South Platte River. From there the river flows into reservoirs feeding the needs of Denver.

Hoosier Pass, on Route 9 south of Breckenridge, marks a transition for urban trans-divide watershed extensions, from Denver and its extensive suburbs and northern cities, to the urban trans-divide watershed extensions of Colorado Springs, and the eastern slope’s southern cities.

While Denver captured some of the Blue River and took it over the Divide through the Roberts Tunnel, Colorado Springs takes some of the Blue River and takes it over the Divide in the Hoosier Tunnel.

The Combination Area at the north portal of the tunnel, on the west side of the Divide, connects to other tunnels and aqueducts in the Blue River Diversion Project, including the Quandary Tunnel and the McCullough Tunnel, which capture water from the western side of the Blue River watershed.

From there the 1.5-mile long, ten-foot diameter Hoosier Tunnel runs under the Divide, flowing by gravity, and opens into a spillway on the southern side.

The spillway descends into the Montgomery Reservoir. From there the water flows out from under the dam into the Middle Fork of the South Platte River. At the town of Fairplay, water is removed from the river and goes to Colorado Springs via the 30-inch Montgomery Pipeline.

The tunnel was completed in 1951, and the reservoir in 1957.

Hoosier Pass was the site of the Hoosier Ditch, which was the first recorded trans-divide water diversion in the state. It consisted of two ditches, that collected water from the west side of the divide, and converged on the pass, where it drained into the Middle Fork of the South Platte River.

The ditch was first recorded in 1860, to supply water for the placer mining operations down river, and was further enhanced in 1929. The city of Colorado Springs has since purchased the water appropriation, and diverts the water through the Hoosier Tunnel.

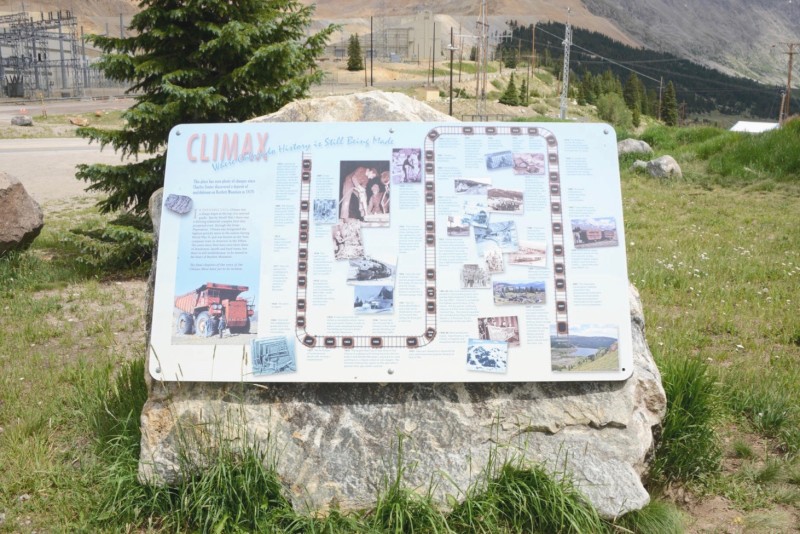

From Hoosier Pass, the Continental Divide heads west, following the mountains north of Leadville. Six miles west of Hoosier Pass, the Divide enters the altered landscape of the Climax Mine.

This was the largest molybdenum mine in the world, and was the origin of the company that is now called Climax Molybdenum, which operates this site as well as the Henderson underground mine, which has replaced this as the largest molybdenum mine in the nation, in output.

The mine at Climax is directly on the Divide, and after becoming a surface mine in the 1960s, it has physically altered the topography by reshaping mountains, digging pits, and piling tailings, thus changing the course of the Divide, in ways that have not really been studied or recorded on maps.

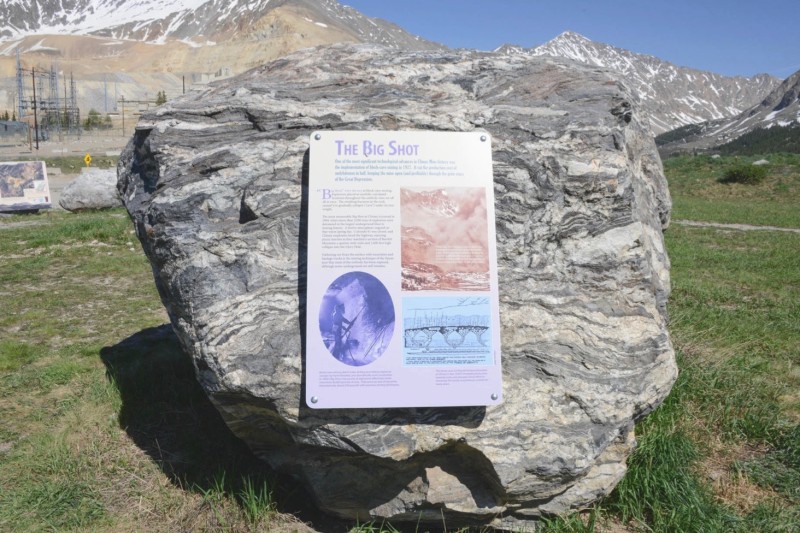

The main mine entrance is on Highway 91, at Fremont Pass, directly on the Divide. The pass was named after the explorer John C. Fremont, as a plaque on a rock, installed by the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1930, states.

This is the first of several literate rocks installed at the Pass.

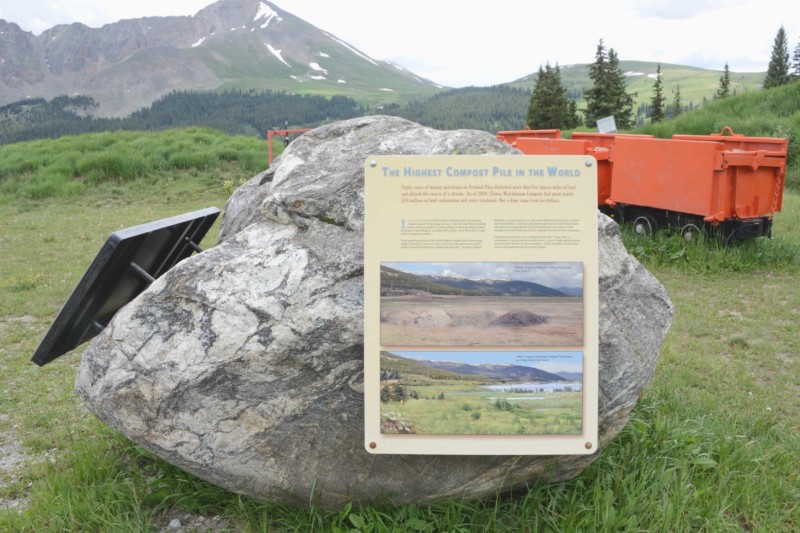

Visitors can enter an interpretive rock garden across from the mine entrance, through a portal made from a rock excavator bucket.

Inside are colorful plaques that address the history of the region, and the massive operation across the road.

Climax got its name from railroad engineers who built a line to the top of the pass—the climax—in the late 1880s, connecting it to the boomtown of Leadville, in the valley below. The mine operated mostly as an underground operation, starting in 1915. By 1926, 75% of all the molybdenum in the world was from here.

Block-cave mining started in 1927, an excavation technique that was pioneered at the mine. The process uses explosives to cause controlled cave-ins in massive vertical cavernous voids. The broken material spills into pre-constructed funnels, under its own weight, and is hauled off over time by train cars that line up under the funnels in a tunnel below.

This technique enabled production to increase dramatically, and by 1957, Climax claimed to be the largest underground mine in the world.

In World War Two, molybdenum was considered an important strategic resource, as it was used to make hardened steel for everything from aircraft engines to armor plating. Most of the nation’s supply at that time came from this mine.

company town, built here in 1936, had as many as 2,000 people in the 1950s. The interpretive rock garden itself is located where the Fremont Trading Post used to be, with a gas station, grocery store and saloon.

The current gate house at the mine entrance is the town’s old police station and jail.

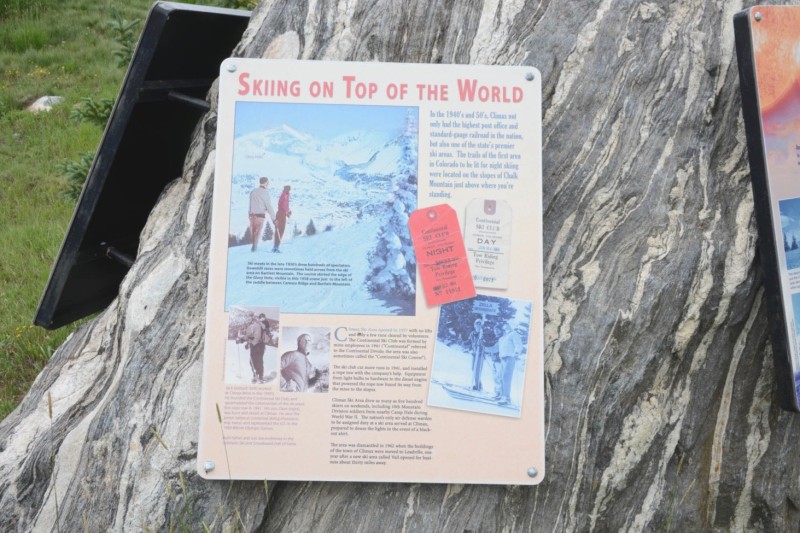

In the 1960s, as open pit mining expanded, the town was in the way, and was removed, and a popular skiing operation was closed. Many of the town’s buildings, and people, moved to Leadville, joining the rest of the workforce, which surpassed 3,000 employees by 1979.

By then a new, more advanced underground operation had opened, the Henderson Mine, up the Divide, and 1970s environmental laws were having an effect on operations here. So in 1982 mining operations here decreased to a trickle, then stopped altogether a few years later.

Though open pit mining started up again in 2012, the emphasis now is mostly about remediation, reclamation, mitigation, and erasure—as much as that might be possible.

Covering a wide area on the Divide, the Climax Mine is at the headwaters of a few river drainages. However, the mine’s wastes have been placed mostly in one of them, the Ten Mile Creek drainage, which flows directly into the Dillon Reservoir, Denver’s largest drinking water reservoir, ten miles from the last of the mine’s tailings dams.

More than half a billion tons of tailings have been impounded in basins constructed along the drainage of the creek, creating new land masses of waste material covering around six square miles. State Highway 91 has been moved five times over the years to make room for new tailing ponds.

Some of the tailings are covered with compost and other material to help stimulate plant growth.

The acidic mining waste water is treated with lime to help precipitate out heavy metals, before the water flows out the end of the last impoundment dam into the creek. Interceptor canals also catch water on slopes before it drains into the tailings ponds, diverting it downstream around the tailings impoundments.

The remains of several historic mining towns existed along Ten Mile Creek, including Kokomo, a town which had 12 hotels and 20 saloons in the late 1870s.

A monument for the “highest Masonic lodge in the USA” was erected overlooking the tailings that now cover it, and these other historic sites as well.

In addition to all the material that is moved from one side of the Divide to the other at the mine, water has been diverted too. A major source of water for the mine and reclamation efforts comes from the Arkansas Well and its reservoir, located below Fremont Pass.

The water is removed from the headwaters of the Arkansas River, which flows down the eastern slope, and is pumped over the divide to be consumed by the mine, which flows down the western slope, through Ten Mile Creek.

This may be the only instance, on the entire Continental Divide, where water is taken from the eastern slope, and delivered to the west. (The Vasquez Tunnel sort of does this too, but its waters originate from the west, through the Gumlick Tunnel, and travel back to the east slope through the Moffat Tunnel.)

In this case, though, since the drainage from Ten Mile Creek goes into the Dillon Reservoir, which drains into the Roberts Tunnel as part of Denver’s water supply, this water finds its way back to the east slope too, eventually.

Six miles further down the Continental Divide, from the Climax Mine, is Tennessee Pass, an important pass, historically.

The area was explored by John C. Fremont and Kit Carson in 1845, as the nearby State historic plaque attests.

Also at the pass is the Ewing Ditch, which was among the first trans-continental water diversions on record, and may be the oldest one still in use.

Constructed in 1880, it extends for a mile up the side of Piney Gulch, capturing drainage that would otherwise go into the Colorado River, and moves it over the Divide where it drains into the Arkansas River watershed.

Around a thousand acre-feet of water passes through the ditch annually, measured by a flow gauge on the Divide. It has been owned by water managers for the City of Pueblo since the 1950s, and helps furnish water to that community, south of Colorado Springs.

There is a small ski operation on the Divide, east of the Pass.

Two miles west from the pass another water ditch extends northward from the Divide for a few miles, to collect drainage from the western slope.

The ditch provides more than 2,500 acre-feet of water a year to the city of Pueblo, measured by a flow gauge at the pass.

Known as the Wurtz Ditch, it was built in 1929, purchased by water managers from the city of Pueblo in 1938, and extended in the 1950s. It is one of around 40 trans-Divide ditches and tunnels carrying water from the western slope to the eastern slope.

Tennessee Pass is mostly remembered as an important railway route over the Divide.

A narrow gauge railway was built over the pass from Leadville in 1881. At that time Leadville had a population of around 30,000, among the largest cities between St. Louis and San Francisco. A few years later a tunnel was bored through the mountain, and the rails were converted to standard gauge.

The line connected to Aspen, and was a busy route between Denver and the West for a few decades.

A new and larger tunnel opened next to the old one in 1945, though traffic was already diminishing, favoring the shorter route through the Moffat Tunnel, which opened in 1928. The last train through Tennessee Pass came through in 1997, and the tracks have been quiet ever since.

In 2012, part of the older train tunnel collapsed, creating a sinkhole in the highway above it. That tunnel was sealed off. The 1945 tunnel remains open, and the route has recently been considered as a potential backup for transcontinental freight—if the Moffat Tunnel were to close, Union Pacific would have to reroute traffic out of the state into Wyoming.

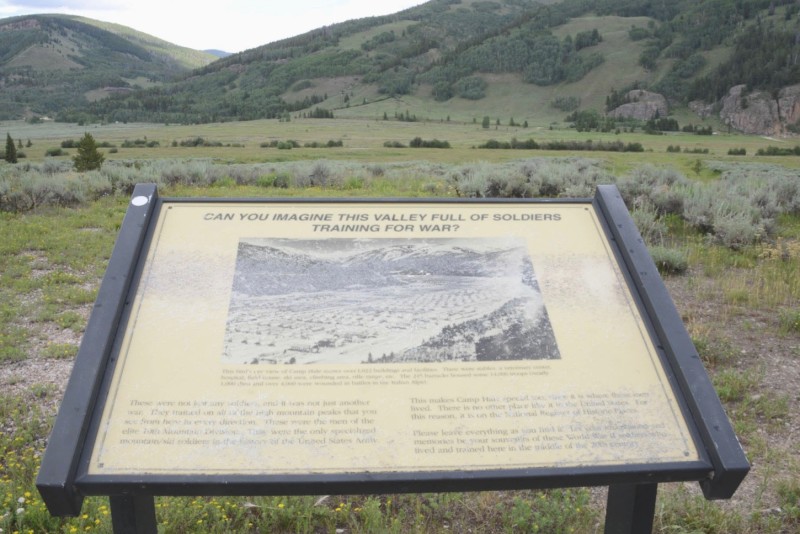

During World War Two, the Army’s 10th Mountain Division, based nearby at Camp Hale, trained in the mountains around Tennessee Pass, as part of their preparations for alpine warfare in Europe.

Based out of Camp Hale, five miles north of the Pass, the area continued to be used for cold weather and high altitude military training. From 1959 to 1965 the CIA trained Tibetan Freedom Fighting troops there.

In 1966 Camp Hale was closed and turned over to the Forest Service, and its remaining buildings removed.

Homestake Tunnel is another water tunnel taking water from the west, to the east. The tunnel is five miles long, and connects Homestake Reservoir to Turquoise Lake.

The Homestake Reservoir is fed by the Missouri Tunnel, which is part of the Homestake Collection System, built by the front range cities of Colorado Springs and Aurora, in the 1960s. The tunnel originates through a portal at the bottom of the reservoir.

After crossing under the Divide, the Homestake Tunnel emerges from under the mountains into a concrete channel.

As is common in ditches, aqueducts, rivers, and streams, the water flows through a Parshall flume, a box of known dimensions, often constructed in concrete, so that the flow can be calculated by measuring the water’s depth at a fixed point, using automatic sensors that transmit the information electronically.

From there the water continues flowing towards the Turquoise Lake, another reservoir, a few hundred yards further away.

Another six miles down the Divide, from the Homestake Tunnel, is Hagerman Pass, a remote track over the Divide under which three trans-divide tunnels pass: the Boustead, Ivanhoe/Carlton, and Hagerman Tunnels.

The Hagerman Tunnel was a 2,150-foot long railroad tunnel constructed in 1887 to serve local mining towns. It was soon abandoned after being replaced by the 9,300-foot long Busk-Ivanhoe Tunnel, built along the same line, 575 feet lower in elevation and with fewer grades, in 1893.

The Colorado Midland Railroad, which built the Busk-Ivanhoe Tunnel, went bankrupt. In 1922 the tunnel was turned into an automobile tunnel, renamed the Carlton Tunnel, with State Highway 104 using it and the old railroad grade, until 1942, when the road was abandoned.

The tunnel is now used to carry water over the Divide, in a concrete tube, from the Ivanhoe Reservoir, on the western slope, to Busk Creek, outside the tunnel’s east portal. From there it flows into Turquoise Lake, and is allocated for use by the cities of Pueblo and Aurora, Colorado.

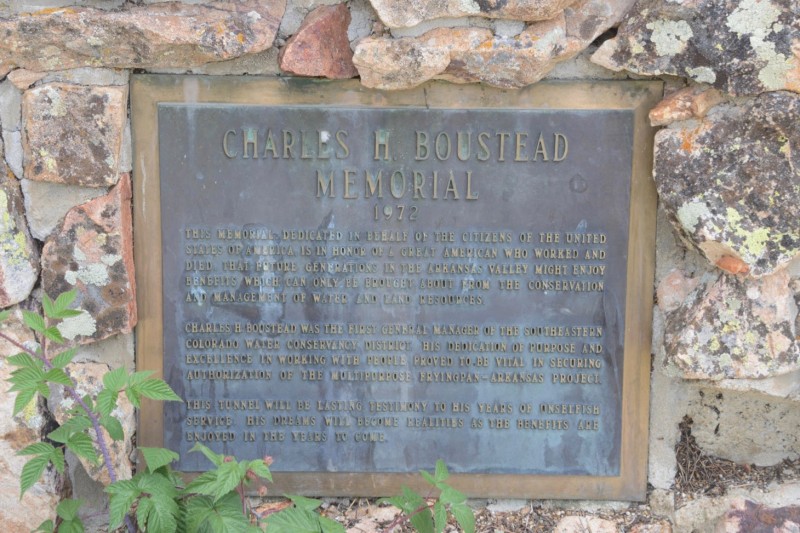

The third tunnel crossing the Divide under Hagerrman Pass is the Boustead Tunnel. It opened in 1972, carrying water under the mountains for 5.5 miles, from the Fryingpan River to Turquoise Lake, where it emerges through the tunnels east portal.

The tunnel is part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, a large-scale water capture and storage project, that was under construction from 1964 to 1981, by the Bureau of Reclamation.

The project is similar to the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, which provided trans-Divide water to eastern slope communities north of Denver, though in this case it serves cities on the southern front range including Colorado Springs, Pueblo, and La Junta.

A total of five reservoirs, 22 tunnels, and 87 miles of conduits are part of the system, on both sides of the Divide. But the Boustead Tunnel is the systems main link over the Divide itself.

The tunnel carries around 70,000 acre-feet per year, which spill into a channel and flow towards Turquoise Lake.

Turquoise Lake, a few miles west of Leadville, is a large reservoir constructed in the late 1960s as part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project.

The water enters the lake’s western end, across from where the Homestake Tunnel drains into the lake.

The reservoir was formed by building the Sugar Loaf Dam, and flooded many old mines and a few old mining towns.

At the base of the dam the water enters the Mount Elbert Conduit, an 11-mile long covered channel, buried just beneath the surface, that flows through the headwaters of the Arkansas River to the Mount Elbert Forebay, at the base of Mount Elbert, the highest mountain in the state, just east of the Divide.

The forebay drains into a tube that descends down the slope to a power plant on the edge of the Twin Lakes.

The power plant and the forebay were constructed as part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project.

When not generating power, water is pumped back up to the forebay from the power plant.

The Twin Lakes used to be two small ponds along Lake Creek, before the Twin Lakes Dam was built for the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, which flooded the area and serves as a reservoir for the pumped storage project, and other end users of the water.

End users of the water include the cities of the eastern slope, but also agricultural users down the arid watershed of the Arkansas River, which flows past Pueblo, through Wichita, Kansas, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, then across the state of Arkansas, where it meets the Mississippi.

Ten miles west of Twin Lakes, up Lake Creek, Highway 82 climbs up to Independence Pass, the second highest paved crossing of the Continental Divide.

Independence Pass, ten miles south down the Divide, from the mostly disused tunnels of Hagerman Pass, is a busy road crossing of the Divide. The highway continues west to Aspen, and is active with biking and tourists.

In 1882, a toll road was built over the pass, though traffic dropped off when the railroads got to Aspen a few years later. In the 1920s, the State of Colorado started maintaining the road as State Highway 82.

The modern highway is closed for half the year because of snow, though the old toll road was kept open year around.

Early use was spurred by the mining town of Independence, located a few miles west of the pass, and the proximity of the boomtowns of Leadville and Aspen.

The town and other historic sites and overlooks are maintained by the Aspen-based Independence Pass Foundation, and the volunteer group Friends of Independence Pass.

Two miles south of Independence Pass, another water tunnel sneaks invisibly under the Continental Divide. This is the Twin Lakes Tunnel, which begins on the west side of the Divide at the Grizzly Reservoir and dam.

The caretakers live in a remote home next to the reservoir, and drive through the narrow four-mile long tunnel, when it has low water, to get to Leadville. It’s a long way around, otherwise, especially when Independence Pass and the surrounding area is snowed in for the winter.

The tunnel emerges from the other side of the Divide at its eastern portal.

It is said to be as straight as a rifle barrel, and that you can see one end all the way to the other, a pinprick of light four miles away.

The tunnel was built in the 1930s, and around 40,000 acre-feet per year flow through the tunnel as measured by the Parshall flume at the east portal.

It is owned by the Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Company, whose shareholders are the City of Colorado Springs, the Pueblo Board of Water Works, the City of Aurora, and other eastern slope communities. The water flows into Lake Creek and to the Twin Lakes Reservoir.

South of Independence Pass, the Divide runs west of the Arkansas River, and goes through a remote, lofty phase, passing through Mt. Harvard (14,414 feet), Mt. Yale (14,194 feet), and Mt. Princeton (14,197 feet). Only one maintained road passes through this 30-mile stretch, at Cottonwood Pass, a remote, meandering, dirt road.

This part of the Divide is also crossed by an abandoned railway tunnel, east of the old railway and mining town of Pitkin.

This was the Alpine Tunnel, a 1,772-foot long tunnel topping the Divide, for a narrow gauge rail line that ran from Denver to Gunnison. It opened in 1882, and was the first tunnel crossing of the Divide in the state. It was abandoned in 1910.

Both ends of the tunnel have been blocked by collapse and landslides.

Volunteers have preserved some of the remains at the west portal, including part of a turntable, telegraph office, and station platform, despite the fact that the road to it is often impassable, covered by landslides.

Southbound, the Divide is crossed by pavement again at Monarch Pass, for the first time since Independence Pass.

Highway 50, a major highway that runs across the southern half of the state, goes over the pass, between Salida and Gunnison.

North of the main pass is Old Monarch Pass, on a dirt road.

This route preceded the new highway, and is slightly higher, and much less traveled.

The main pass, on Highway 50, is one of only two sites directly on the Continental Divide with retail opportunities.

The Monarch Crest gift shop and visitor center has operated here since 1954, though the old log cabin style building burned down in 1988, and was replaced with this 8,000-square foot structure.

The building was made in a modular fashion, using a cluster of ten concrete squares, topped by concrete domes, then covered by eight feet of earth.

Inside is a snack bar and gift shop, often staffed by the owner.

The building is on land leased to the concession by the National Forest, and inside is a National Forest display, which is a bit buried by the retail needs.

There is also a nook for Continental Divide Trail hikers, who can pick up packages mailed to them here, repack with supplies, and charge cell phones.

A relief map shows them where they stand on their long journey one way or the other.

The bathrooms for the gift shop and snack bar are on the eastern side of the Divide; the sewage treatment and septic is on the Pacific side.

Above the parking lot is Monarch Ridge, a point on the Divide 700 feet higher than the Pass.

The concession company built an aerial tram here in 1966. Though there are other trams and lifts at ski hills on the Divide, this is the only purely scenic tram on the Divide, and operates in the summer, instead of the winter.

The tram was made by the Heron Engineering Company of Denver, which makes chairlifts for ski operations around the state. The four-person fiberglass cars were made by the Atlas Engineering Company in Salt Lake City.

The 1,440-foot long diagonal trip to the top takes just a few minutes.

And offers fine views of the pass and the nearby Monarch Ski Area.

The hilltop terminal building has a 30-ton concrete counter-weight on its back side, which holds up the tram cable, and provides even tension on the line.

On top of the tram building is an observation level, ringed by an outdoor deck providing views in all directions, that extend for 150 miles on clear days.

Inside are interpretive overlooks, pointing out surrounding topographic features.

Outside are a variety of electronic transmission and communication facilities, including an AT&T microwave tower, and an automatic weather station, operated by the FAA.

Wind gusts of close to 150 miles an hour have been recorded here, and snow levels average 350 inches a year—30 feet.

Some structures at the top are no longer there.

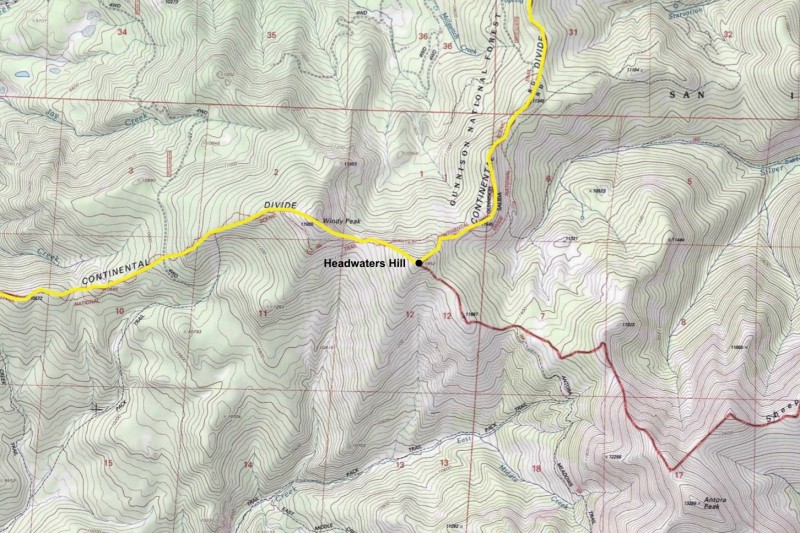

Ten miles south of Monarch Pass, the Divide comes to a peak known as Headwaters Hill. This marks a point on the Divide where the drainage eastward transitions from the Arkansas River to the Rio Grande River. Westward, to the Pacific Ocean, remains through the Colorado River drainage (via the Gunnison).

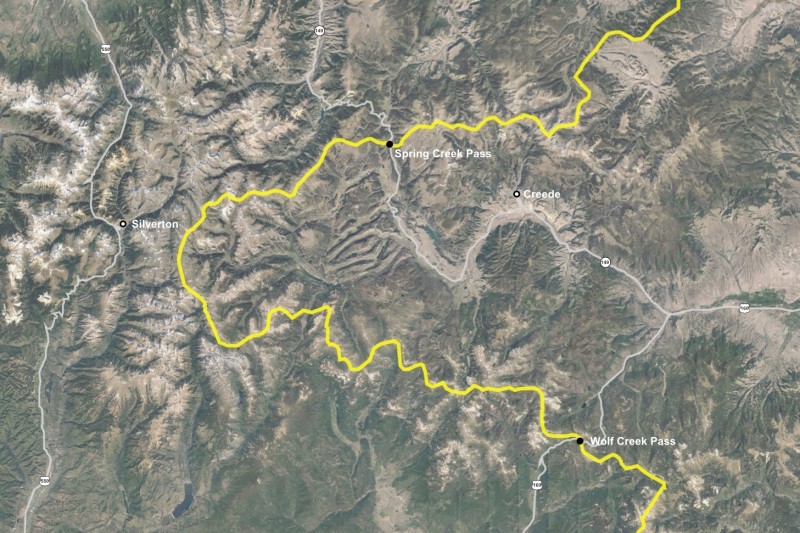

South from Monarch Pass, the Continental Divide heads southwest through remote mountains for more than 50 miles, crossed only by one paved road, Highway 114, south of Gunnison. The next paved road is Highway 149, which crosses the Divide at Spring Creek Pass.

On the western side of Spring Creek Pass is the scenic valley of the Lake Fork River, which flows into the Gunnison north of Lake City. A few miles before the pass, The Slumgullion Earthflow Overlook reminds travelers of the fluidity of even this massive Rocky Mountains.

850 years ago a massive slide known as the Slumgullion Earthflow, dammed the Lake Fork River and created Lake San Cristobal, forming the second largest natural lake in the state.

The hillside is still moving, they say, at a rate of around 20 feet per year.

An information kiosk at Spring Creek Pass describes other local phenomena, including the Continental Divide Trail, which goes through the pass.

A trans-Divide water diversion ditch also goes through the pass, collecting water for around a half a mile in the forest on the western slope.

Known as the Tabor Ditch, it was constructed around 1910 to capture water for irrigation downstream. It is now owned by the Colorado Division of Wildlife, which uses it to help compensate for other water diversions in the watershed. The artificial stream flows next to the asphalt at the pass, to a stream gauge.

The channel is constricted through a small Parshall flume, where its flow is measured and transmitted electronically.

The ditch diverts between 1,550 and 500 acre-feet per year.

The water goes under the highway in a culvert and forms a stream called Spring Creek, a high up tributary of the Rio Grande.

After heading southwest through the spine of the San Juan Mountains, the Continental Divide doubles back, eastward, as if it were repelled by the mining district of Silverton. It snakes around the San Juans until dropping down to 10,800 feet at Wolf Creek Pass.

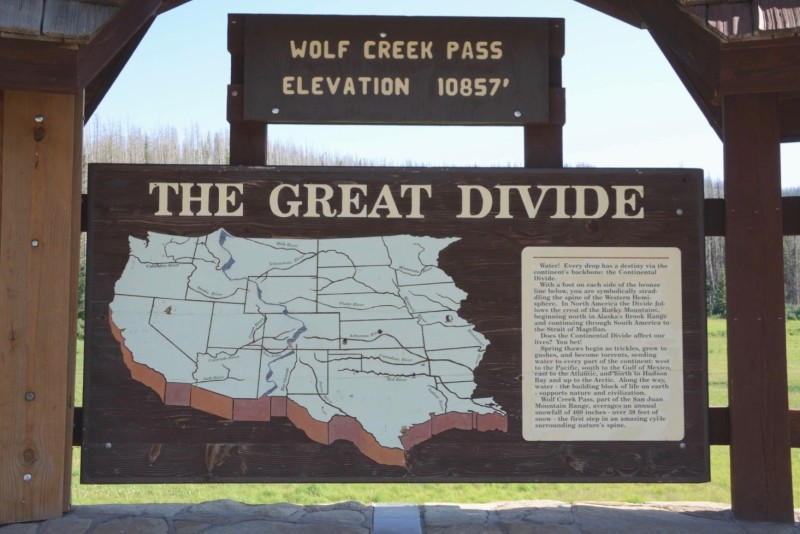

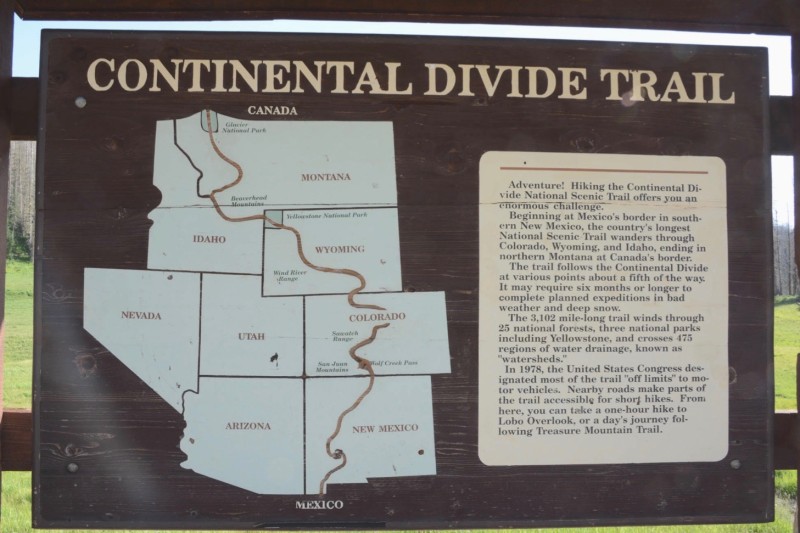

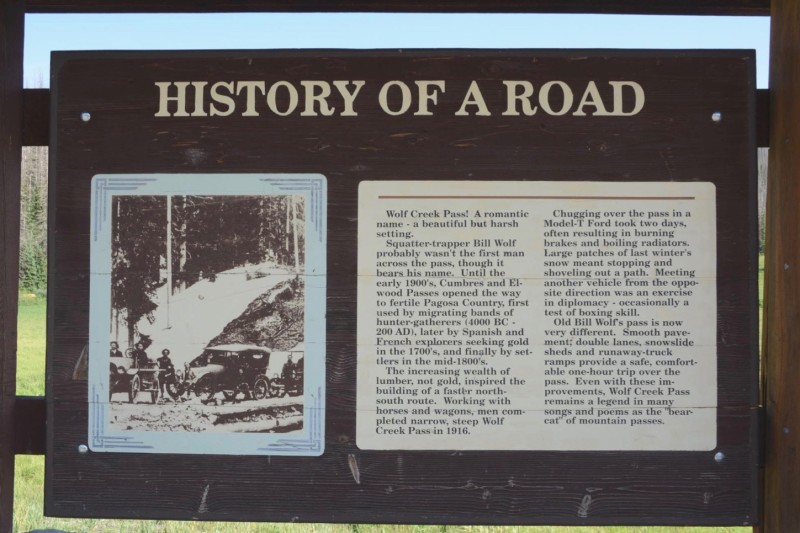

Wolf Creek Pass is on Highway 160, which runs across the bottom of the state from one end to the other.

A nice view of the highway through the pass, and the ski runs of the Wolf Creek Ski Area, can be had from the Lobo Overlook, on the Divide north of the pass.

There is also a busy telemetry tower at the Lobo Overlook.

Amid the spruce trees killed by beetles.

Down below at the pass on the highway is one of the grandest interpretive panels on the Divide, which speaks for itself.

Voiceless behind it is the Treasure Pass Diversion Ditch, which captures water from the western slope and carries it over the Divide. The ditch was built in 1922, to help irrigate the San Luis Valley, on the eastern slope.

It’s a small ditch, diverting around 125 acre-feet a year, as measured by a Parshall flume, on its way out of the Pass.

It is the last of a half dozen small trans-Divide ditches along the Divide between here and Spring Creek Pass, that supplement the flow of the upper Rio Grande. And it’s the last of the 40 or so large and small trans-Divide water diversions within Colorado, the state with the most, by far.

Southbound, Wolf Creek Pass is the last time pavement crosses the Divide in Colorado.

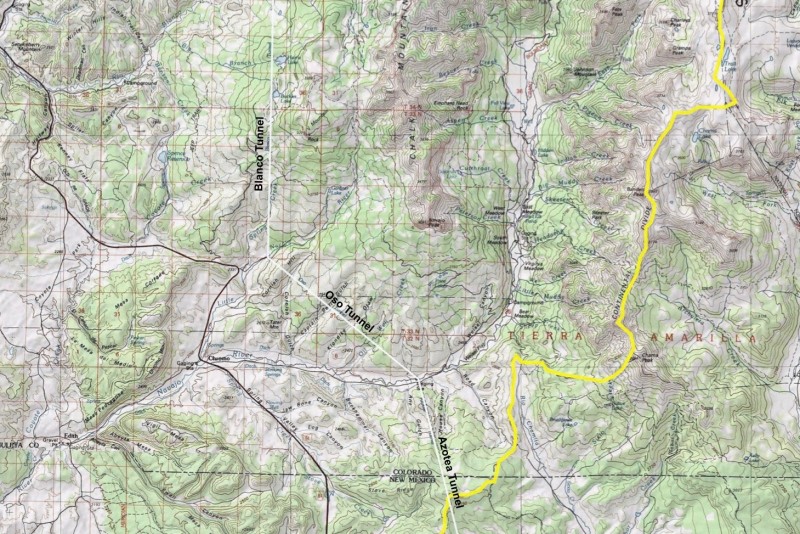

The Oso Diversion Dam is two and a half miles west of the Continental Divide, and two and a half miles north of the New Mexico state line. It is the origin of the Azotea Tunnel, which takes water from the western slope in Colorado, and delivers it to the eastern slope in New Mexico.

The Oso Dam is the collection point for 15 miles of tunnels that collect water from streams on the western side of the Divide and bring it to Oso.

It is part of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s San Juan-Chama Project, which moves water from the San Juan River to the Chama River, to help with irrigation in northern New Mexico, but also to supply more water to New Mexican cities and towns, primarily Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

Constructed in 1970, the Azotea Tunnel emerges from the diversion dam and runs south, underground, for more than 12 miles, crossing under the Divide in New Mexico, before discharging around 100,000 acre-feet of water previously destined for the Colorado River, into the Rio Grande’s watershed.