The Continental Divide in the USA originates where Montana meets the Canadian border. The Divide travels south over the high peaks of the northern Rockies, through Glacier National Park, on a meandering path. Eventually the Continental Divide becomes the boundary between Montana and Idaho, before entering Wyoming at Yellowstone National Park. Despite the remote terrain, there are many curious cultural and historical encounters along the way.

In Canada, the southern part of the boundary between Alberta and British Columbia follows the Continental Divide, so where this provincial boundary meets the international border, set by treaty at the 49th parallel, is where the US portion of the Continental Divide begins.

The Continental Divide in the USA begins in Glacier National Park, a one million-acre park established in 1910, with numerous mountain peaks, lakes, small alpine glaciers, and grand lodges. The US Government bought the initial 800,000 acres that would become the park from the Blackfeet Indians, whose principal reservation covers nearly two million acres east of the park.

20 linear miles south of the border, the Divide crosses pavement for the first time, next to the parking lot for the visitor center at Logan Pass, within Glacier National Park.

At 6,646 feet above sea level, Logan Pass is the highest point on the Going to the Sun Road, the only road through Glacier National Park.

Going to the Sun Road was built between 1921 and 1932, and given the steep topography, is considered an engineering landmark.

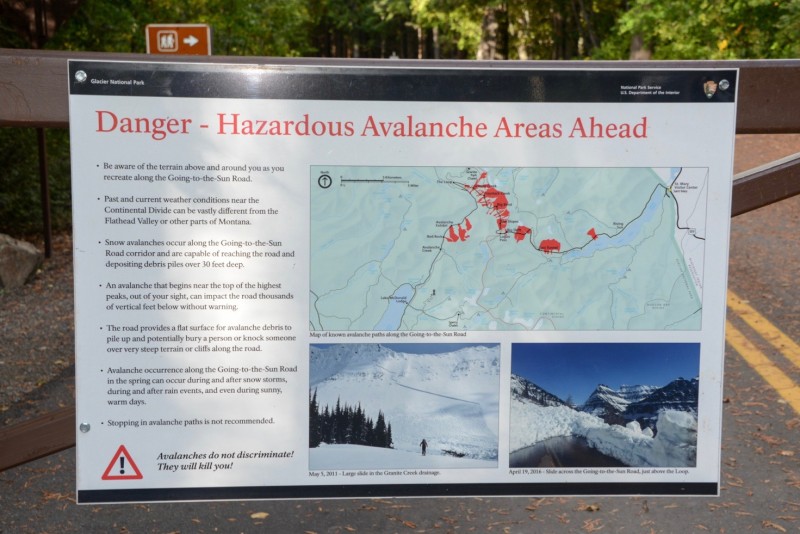

Going to the Sun Road is closed for much of the year, due to snow and avalanche danger.

At the height of winter, drifts sometimes bury the road at Logan Pass in as much as 80 feet of snow.

The opening sequence of the 1980 Stanley Kubrick film The Shining was shot along this road, and shows the doomed family’s little yellow VW Bug heading towards Logan Pass.

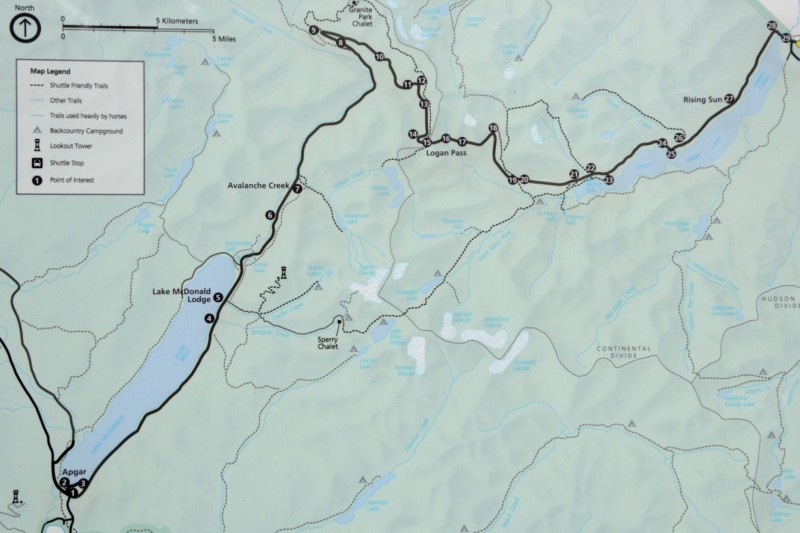

Going to the Sun Road is 50 miles long, and connects the east entrance of Glacier National Park to the west entrance.

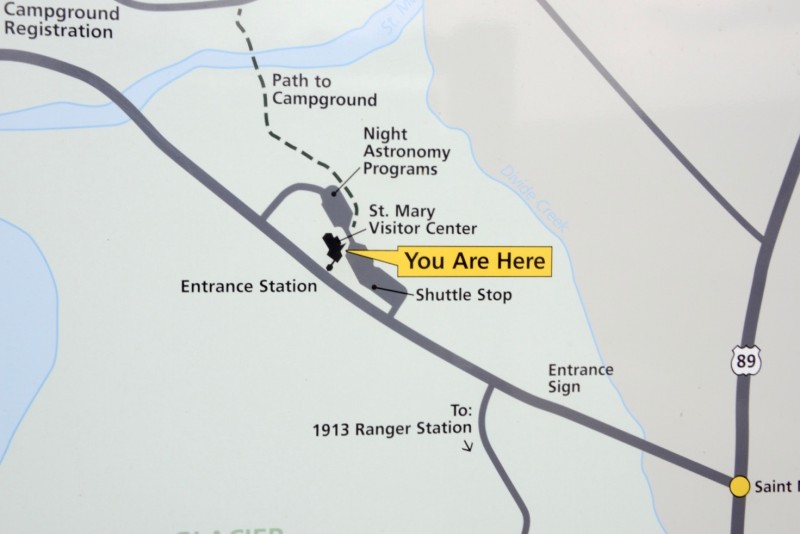

The east entrance is at the town of St. Mary, where there is a visitor center, and a gate where people pay the park entrance fee.

The Glacier National Park visitor center has a diorama showing the park’s convoluted topography.

At the other end of the road is the west entrance to the park, and the community of West Glacier.

Logan Pass is at the halfway point, and the apogee, of the Going to the Sun Road.

A few miles south of Logan Pass, the Continental Divide reaches its highest point in the park, at Mount Jackson, 10,052 feet above sea level. The highest peak in the park, however, is Mount Cleveland, 10,479 feet, which is several miles east of the Divide, with all sides of it draining into the Atlantic.

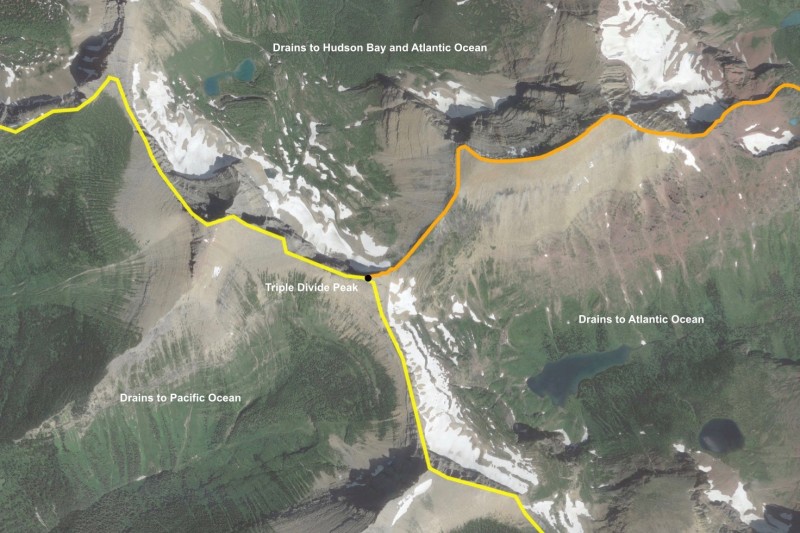

A few miles further, the Divide goes through a mountain top called Triple Divide Peak, a place that challenges the notion of a binary Continental Divide, as another divide, the Laurentian Divide, emanates from this peak, defining a third drainage basin that exists in a small portion of Montana.

The east side of the peak is drained by Atlantic Creek, which drains to the Cut Bank River, which drains into the Marias River, which drains into the Missouri River, which drains into the Mississippi River, which drains into the Atlantic Ocean.

The west side of the peak is drained by Pacific Creek, which drains into Nyack Creek, which drains into the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, then flows past the west entrance of the park to the Flathead River, to the Clark Fork River, to the Pend Oreille River, to the Columbia River, which drains into the Pacific Ocean.

The north side of the peak drains into Hudson Bay Creek, which flows into Hudson Bay, in the Canadian north. A dam a few miles before the border, however, diverts much of the flow into the Milk River for agricultural use in Montana, then into the Missouri River, the Mississippi River, and into the Gulf of Mexico. Only a small portion of this water actually gets to Hudson Bay.

Just outside the southern end of the park is Marias Pass, where the Continental Divide, heading south, crosses its second road, US Highway 2.

Highway 2 is the country’s northernmost continental highway, running from the Great Lakes in northern Michigan to Puget Sound in Washington State.

A wayside at Marias Pass has a number of monuments, the largest of which is a stone obelisk. It was erected by the Federal Highway Administration in 1930, when US Highway 2 through the pass was completed.

It is dedicated to Theodore Roosevelt, in commemoration of his leadership in conservation, and quotes him as saying “The forest problem is in many ways the most vital internal problem of the United States.”

Next to the obelisk is a more modest monument commemorating the trapper and prospector who lived here and gave up his land for the Roosevelt memorial.

On the other side of the obelisk is a figurative statue of John F. Stevens, the railroad engineer who “discovered” the pass, which had long been in use by Blackfeet and other tribes. Stevens was there when the statue of him was dedicated in 1925.

Great Northern Railway built its main line over Marias Pass in 1891, one of a few transcontinental rail lines connecting the nation in the late 19th century that enabled the Seattle region to rise as a metropolis.

Great Northern Railway was also the primary developer of Glacier National Park, with a railroad station at West Glacier and East Glacier, providing access to the area decades before roads were built over the Divide.

Amtrak’s Empire Builder passenger railway still stops at West and East Glacier, bringing tourists who stay in the grand Swiss Style lodges built by Great Northern inside and outside the park.

At Essex, a community on the highway and railway west of the pass, is a railroad yard for the Great Northern, where helper engines once were based to help push eastbound trains up the steep slope towards the divide, and where maintenance and snow removal crews are based.

In 1939 Great Northern built a lodge, which overlooks the railroad yard, to house its crews at Essex. It is now open to the public as the Izaak Walton Hotel.

Visitors can choose to sleep inside a converted Great Northern locomotive.

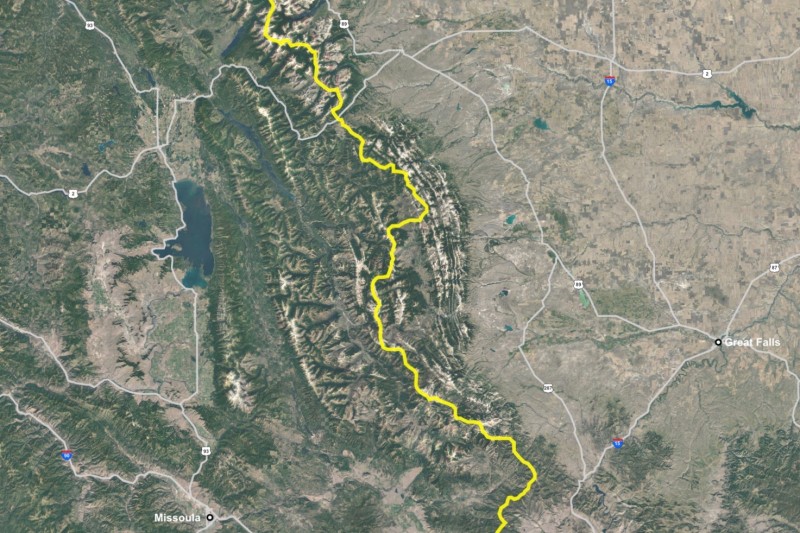

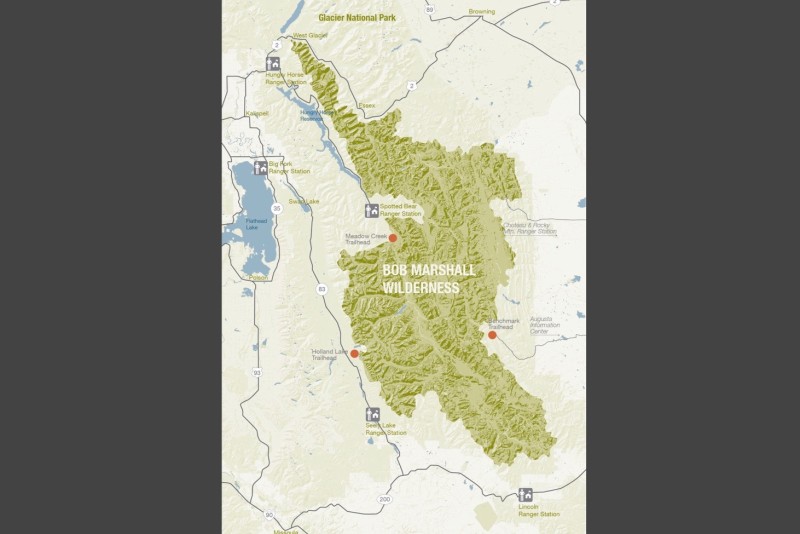

From Highway 2 and the rail corridor over Marias Pass, it is a hundred linear miles till the next road over the Divide. Most of the region is the Bob Marshall Wilderness, a national forest larger and more remote than Glacier National Park.

Bob Marshall was a federal forester, and co-founder of the Wilderness Society. The area was named in his honor when established as part of the Wilderness Act in 1964. Motorized and mechanical equipment (even bicycles) are banned from the area. This is one of the largest roadless areas in the nation.

State Highway 200 is the first road to cross the Continental Divide south of the Bob Marshall Wilderness, at Rogers Pass.

The Continental Divide hiking trail, which follows the Divide for much of its 3,100 miles between Mexico and Canada, goes over Rogers Pass.

The few dozens of southbound through-hikers walking the trail annually, who have been in the wilderness for more than a week up to this point, encounter the asphalt here. A set of stairs helps them transition through highway department terrain.

A few miles south, the Divide crosses another road, highway 279, at a point known as Flesher Pass.

Here too a reinforced pathway helps hikers on the Continental Divide Trail transition between road and trail.

Water bottles are sometimes stashed behind the sign to help thirsty hikers.

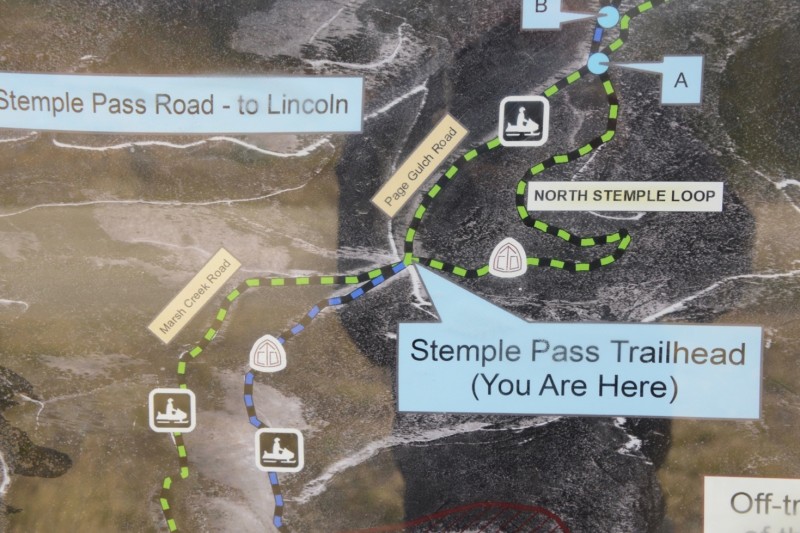

Hikers following the trail southbound encounter the next road in 11 miles, a dirt crossroads on the Continental Divide known as Stemple Pass.

The pass has picnic tables, a pit toilet, and some signage, and in the winter is used as a cross-country ski area.

A road heads north out of Stemple Pass to the town of Lincoln, ten miles away.

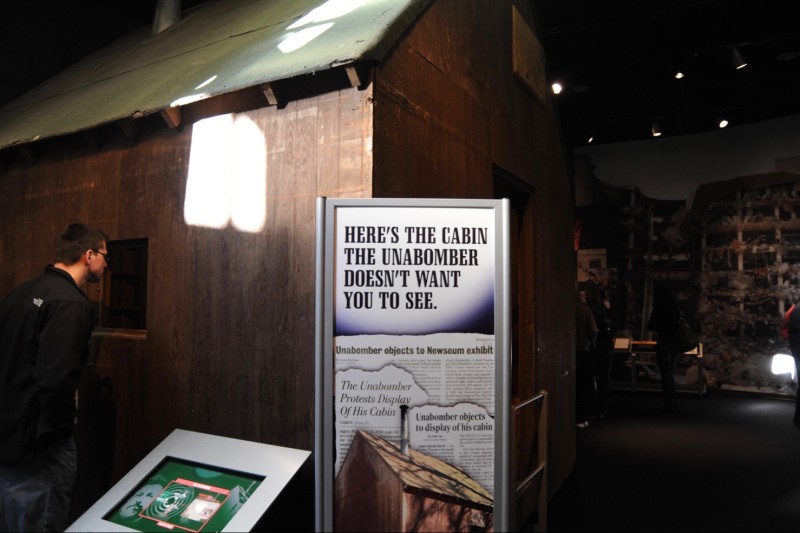

Along the way the area becomes developed with scattered cabins and larger homes. It is here, just off Stemple Pass Road, where Ted Kaczynski, who became known as the Unabomber, built his cabin and worked on his manifesto and mail bombs.

After he was arrested the cabin was removed and traveled around the country a bit, before it found its way to a museum about the news industry in Washington DC called the Newseum.

The site off Stemple Pass has been sold, and its current owners are not interested in sharing its history.

Some Unabomber tourists still visit Lincoln and go to the library to see the chair he sat in for many days and hours of reading.

Most people in town want to forget this part of its history, and look for other things to put it on the map.

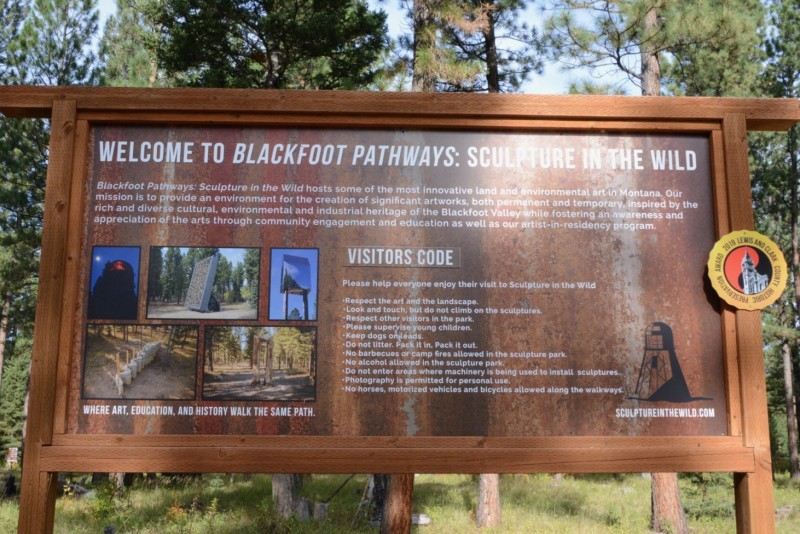

Like Blackfoot Pathways, a contemporary art sculpture park in the woods on the edge of town.

Mullan Pass is a dirt road over the Continental Divide west of Helena, Montana. The road is named after the Army engineer that identified the Divide and had a road built over it in 1860, which was reportedly the first engineered road to be built in Montana.

Like many road passes over the Divide, there are buried utilities crossing here as well, in this case a gas pipeline.

The Continental Divide Trail also crosses the road here.

The railroad, however, dominates Mullan Pass, with winding spindly bridges and a tunnel. This was the first main line transcontinental route for the Northern Pacific Railway, which opened in 1883, connecting Minnesota to Puget Sound (like its chief rival, the Great Northern Railway did by a more northerly route ten years later).

The tunnel, 330 feet lower than the top of the pass, is the longest rail tunnel in Montana, even though it was shortened by 400 feet in 2009 (to 3,426 feet).

When the railroad tunnel was originally built in 1883, it was less than 13 feet wide, which provided less than three inches of room (to spare) for some loads. Work done in 2009 widened it by three feet, and increased its height by 5 feet, allowing more air in the tunnel, which helps to keep the high horsepower helper engines from overheating.

The line is now operated by Montana Rail Link, a local rail system with 900 miles of track, including this stretch between Helena and Missoula.

Four miles south down the Divide from the Mullan Tunnel is US Highway 12, the only highway heading west from Helena, Montana’s state capital.

The modern highway goes over the Divide at McDonald Pass, over an old toll road that first opened in 1866.

On a rise on the south side of Mullan Pass are ruins of a former vista point.

An active microwave relay tower, a common sight at mountain passes, is now adorned with cellular and other antennas.

A less common sight at the pass is an old airway beacon, now abandoned. Though it post-dates the incident, it makes an interesting memorial to a singular aviation event that occurred nearby in 1911, when a pilot named Cromwell Dixon became the first person to fly over the Continental Divide.

He landed his biplane and wired New York from the west side of the Mullan Tunnel, to announce he had made it, so he could collect the $10,000 award. Dixon continued on to a fair in Spokane, where he died in a crash two days later.

Across from the old vista point at McDonald Pass is what looks like an old western fort, slightly visible through the trees. It’s a former locally famous attraction called Frontier Town, built by a visionary Wild West enthusiast named John Quigley. Starting in 1948, it grew into a rambling self-built structure with 48 rooms, and things like the “largest one-piece bar in the world.”

Quigley died in 1979, though the place remained open, run by his family. Financial trouble forced the sale of much of his collection in the 1990s, and the property was sold at auction in 2001 for $190,000, and is now a large, crumbling, private residence, off limits to the public.

South from McDonald Pass, the Continental Divide meanders along the ridgeline of the Boulder Mountains for more than 40 miles, with just a few small forest service trails and tracks passing over the Divide, and a few old mining areas littering its flanks.

The Divide drops out of the Boulder Mountains just north of Butte, and crosses Interstate 15 at Elk Park Pass.

The old road, on the west side of the interstate, is abandoned and dead-ends where mining operations begin, south of the Pass.

On the east side of the interstate is a dirt road that climbs up the hill, crossing the Divide a few times along the way.

Along the ridgeline at the top of the Divide are antennas for TV and radio stations in Butte.

After passing through a final gate, the road reaches its end, at the back side of Our Lady of the Rockies.

Our Lady of the Rockies is directly on top of the Continental Divide, and looms above the town and mining pits of Butte. It was the vision of a local resident, Bob O’Bill, and was designed by Laurien Eugene Riehl, a local mining engineer.

The sculpture was fabricated off site, and airlifted in five sections which were stacked on top of one another over a few relatively wind-free days in late December 1985, by a military team using a Sikorsky Sky Crane helicopter.

Our Lady of the Rockies, at 90 feet tall, is likely the fourth largest Virgin Mary in the world, following a 153-foot one in Venezuela, a 148-foot one in Bolivia, and a 108-foot one in France. All of which are soon to be overshadowed by a 315-foot tall statue of the virgin under construction in the Philippines which is expected to be completed in 2021.

A door in the back leads inside the sculpture, but visitors are not allowed to climb up too far inside, and there is no viewing area at the top (as there is at the comparably-scaled Statue of Liberty, which is 111 feet from foot to crown).

Visitors can however leave memorials of their own inside, if they bring them.

The view from the top looks westward, over Butte, and the Berkeley Pit, where mining stopped in 1982, and it began filling up with acidic water. In the foreground is Interstate 15, and above it the Continental Pit, which is still actively mining copper and molybdenum, at the base of the Continental Divide.

Homestake Pass is the first pass south of Our Lady of the Rockies’ perch on the Continental Divide, five miles away, and 2,117 feet higher up.

Homestake Pass now carries Interstate 90, which connects Boston to Seattle, built through here in 1966.

The pass was first developed by Northern Pacific Railway in 1889, to connect Butte with its mainline to the east, at Logan. Railways extend westward from Butte, along a corridor now shared with Interstate 90.

BNSF ended up owning the line through the pass, and continued passenger service until 1979. The company stopped using the tracks in 1983, as its grades are steep for freight, and the line through the Mullan Tunnel, west of Helena, is more efficient.

Pipestone Pass used to be the main highway over the Divide, connecting Butte to points east (formerly known as Highway 10, it is now Highway 2). When Interstate 90 was built through Homestake Pass, four miles to the north, use of this road diminished.

The transcontinental railway known as the Milwaukee Road came through here in 1909, connecting Chicago to the Pacific Northwest. The line, now abandoned, went through a tunnel under Pipestone Pass.

The Milwaukee Road eventually lost out to BNSF, which abandoned the line in 1980, after which the tracks were removed.

Though crumbling and dangerous, the half-mile long tunnel is one of several along the two abandoned railways southwest of Butte, enjoyed by teenagers and other explorers.

The Continental Divide loops around Butte, entering the region from the north, and departing to the west.

Ten miles south of Butte, the Divide goes through Deer Lodge Pass, crossing Interstate 15 for the second time.

The Divide is crossed again by the bumpy and seldom used Highway 569, south of Anaconda, where the smelter that once served the mines at Butte was located. After that the Divide snakes through the crest of the Anaconda Range, passing through 10,000-foot peaks, until it hits Idaho, near Lost Trail Pass.

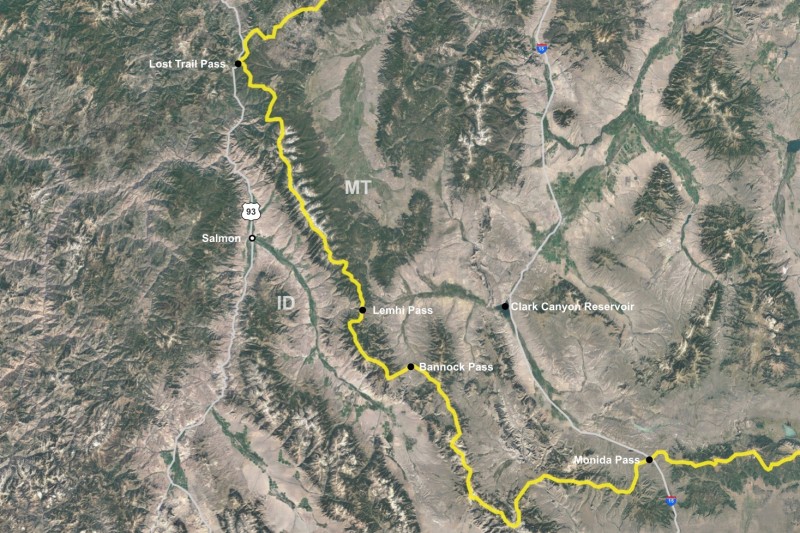

The Continental Divide meets the Idaho state line near Lost Trail Pass, traversed by US Highway 93 (though the actual intersection point is in the woods a half mile east of the road). Southbound, from this point on, the Divide line is the state line, all the way to Wyoming.

Lost Trail Pass has a roadside rest for Highway 93, which is a major north/south two-lane highway, running from the Canadian border to southern Arizona.

There is also a ski resort at the pass, the Lost Trail Ski Area. Here the state line heads northward, following a ridge line in the Bitterroot Mountains, and the route of a chairlift. Trails at the resort are in both Idaho and Montana.

As its name suggests, Lost Trail Pass is a complicated and even contradictory place. Signage at the wayside describes some of the history of the region, which includes confusion about where the legendary pathfinders Lewis and Clark were, exactly, when they came through here in 1805.

Prior to the highway coming through in the 1930s, the main pass used by travelers in the region was Gibbons Pass, a few miles north, now on a rarely used dirt road. A bit south on the Divide is Big Hole Pass, which was also used by early travelers, and near that is Chief Joseph Pass, which is also on the Divide, less then a mile from Lost Trail Pass, on Highway 43.

These names reflect a famous conflict involving the Nez Perce Indians, known as the Battle of the Big Hole.

The battle was among the worst in the months-long 1877 Nez Perce War, where US forces fought with Indians trying to escape to safety in Canada. Some of the story is told at a National Historical Park at the base of the mountains, 12 miles east, where much of the battle took place, a few miles west of the town of Wisdom.

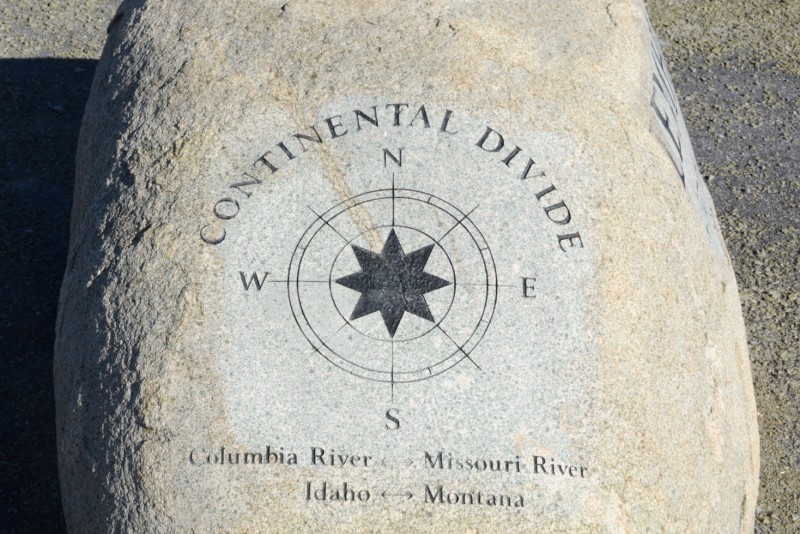

Heading south from Chief Joseph Pass, the Divide follows the crest of the Beaverhead Mountains for 50 miles, with peaks rising to more than 10,000 feet, until the Divide drops to an elevation of 7,373 feet at Lemhi Pass.

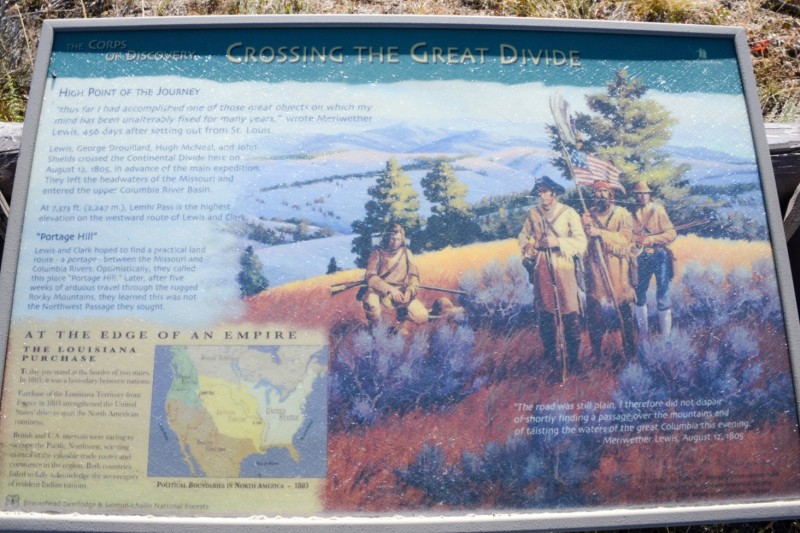

Lemhi Pass was used by Shoshone traveling on horseback as far back as the late 1700s, but became famous after it was used by the Corps of Discovery, otherwise known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, in 1805.

In August 1805, scouting ahead of the rest of group, Meriwether Lewis and three others crossed the Continental Divide for the first time, here.

Lewis then returned to the expedition’s camp on the east side of the Divide, thirty miles back, to meet with the rest of the group, who were slowly dragging their canoes and gear up the last bits of remaining river.

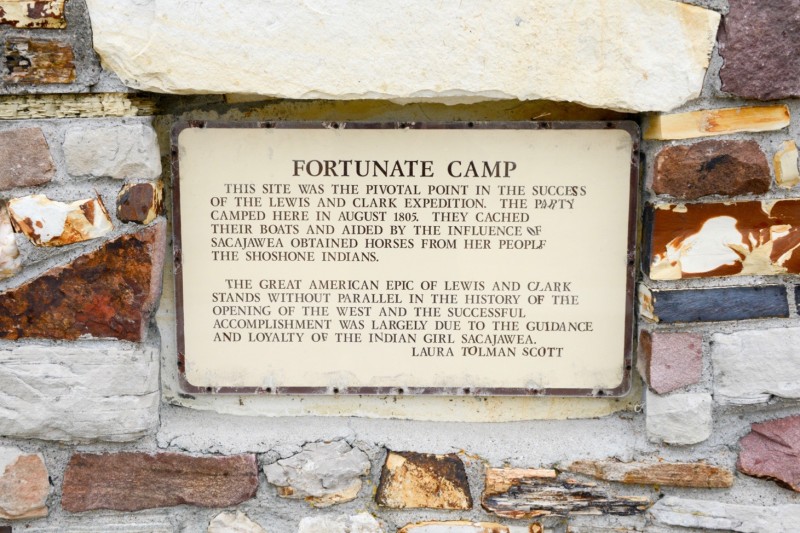

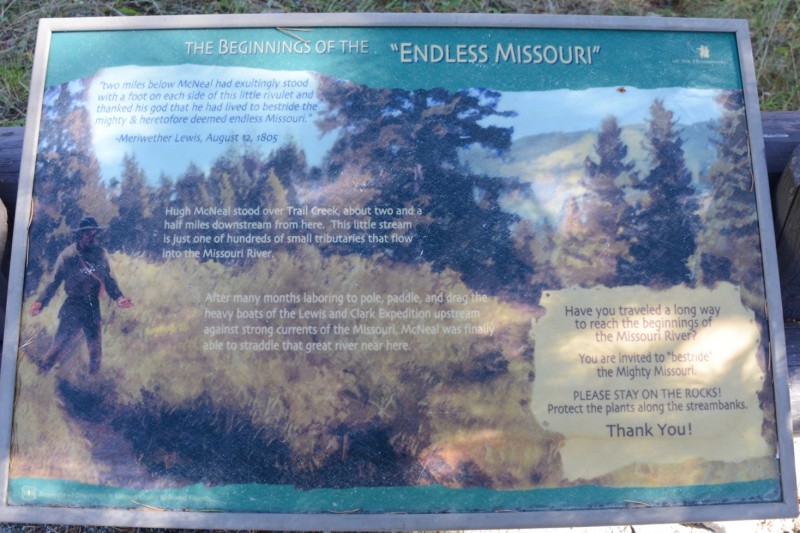

They established Fortunate Camp 30 miles east of the Divide. It was the furthest point up the Missouri watershed they could get with their boats.

The site has been heavily interpreted, including efforts by Laura Tolman Scott, of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

The Corps of Discovery called this Jefferson’s River. It is now called the Beaverhead River, and a battery of interpretive plaques overlooks the site.

The actual site of Camp Fortunate is now under the waters of the Clark Canyon Reservoir, which flooded the valley in 1964, when the Bureau of Reclamation completed the Clark Canyon Dam to control flooding and to provide water to irrigation projects downstream.

On August 23, 1805, the Corps left Camp Fortunate and headed towards Lemhi Pass, traveling with Sacajawea and other Shoshone, leaving their canoes behind. The canoes were filled with rocks, sunk in a nearby pond, and were recovered when William Clark returned heading eastward a year later.

They soon arrived at Lemhi Pass, two weeks after Lewis’s first visit, and called it Portage Hill, as they had hoped that the Salmon River, at the base of the pass on the other side of the Divide, would carry them by boat to the Pacific Ocean.

The river was found to be too small and too full of rapids, but, led by Shoshone, Salish, and Nez Perce tribal members, the expedition finally found navigable water, and trees big enough to build canoes, weeks later at the Clearwater River in northern Idaho, which eventually carried them to the Columbia River, and the Pacific.

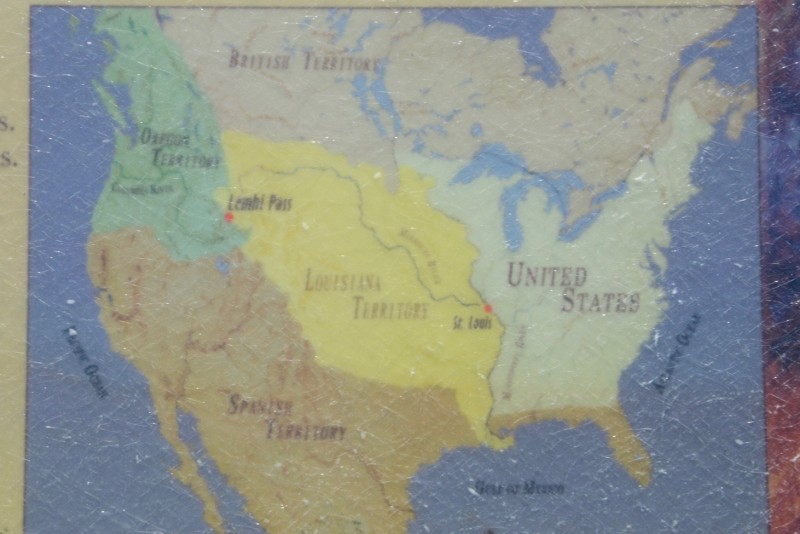

Lemhi Pass was the highest point they would cross on their western trip, and it is where they left the United States, land recently acquired by the Louisiana Purchase, and entered the northwestern territory, still claimed by the British.

Half a mile south of the pass is the Sacajawea Memorial Area, created in 1932 through the efforts of Laura Tolman Scott, of the Daughters of the American Revolution, to honor Sacajawea’s role in guiding the team westward.

Located at the remote and seldom visited interpretive area is the Most Distant Fountain, which for years was assumed to be the source of the Missouri River, as identified by Meriwether Lewis.

The Most Distant Fountain is one of a few springs in the area that create small streams here on the eastern side of the Divide. These springs join tributaries that flow into the Beaverhead River, which begins at the base of the Clark Canyon Dam.

The Beaverhead River meanders relentlessly over the next fifty miles until it joins the Big Hole River to form the Jefferson River, which meanders over another fifty miles until, at Three Forks, the Jefferson River joins the Madison River and the Gallatin River to form the Missouri.

The Missouri, of course, merges into the Mississippi River at St. Louis, where the Corps of Discovery began its journey up the Missouri into the Louisiana Purchase, and on which they returned, a year later, flowing back down the Atlantic side of the Divide.

Bannock Pass is a more modern road over the Continental Divide, 13 miles south of Lemhi Pass. Much of the even grading of the otherwise remote dirt road is from the former Gilmore and Pittsburgh Railroad roadbed, which was built through the pass in 1910 to service mines in Gilmore, Idaho, and an expected boom in population that did not arise.

The railroad ran between Salmon, Idaho and Armstead, Montana, where it connected to another rail line that went to Butte. The railroad operated until 1939, when it was demolished, and its tracks were removed, leaving this automobile road to connect the two valleys on either side of the Divide.

Though Salmon is still a regional population center, Gilmore is a ghost town, and Armstead is under the waters of the Clark Canyon Reservoir.

Abandoned mines and a collapsed railroad tunnel remain at the top of the Divide near Bannock Pass.

There also is a microwave repeater site, now owned by American Tower, like so many mountain-top communication sites around the country - in use, and not.

The Divide curves eastward at the southern end of the Bitterroot Range with no major crossings until it is overtopped by Interstate 15, for the third and last time.

The Union Pacific Railroad also goes through the pass, next to the Interstate.

The railroad line generally follows the Interstate, north to Butte, and south to Pocatello, and Utah.

The railroad line closely follows Old Highway 91, which at times is nearly abandoned in favor of the Interstate.

The Divide rolls on to the east, along the edge of (though some say through) a scrapyard in Monida.

The Divide is also the state line between Montana and Idaho. The pass, and the nearby small community of a half dozen people, gets its name - Monida - by combining the words Montana and Idaho.

The pavement crosses the Divide at Targhee Pass, on Highway 20, just a few miles west of West Yellowstone, the entrance to Yellowstone National Park.

Depending on which way you are headed, you are entering either Montana or Idaho.

Either way, the Continental Divide disappears from the roadscape for a while.

Southbound the Divide meanders for another 20 miles, along with the state line, and continues down Wyoming’s western edge, two miles into Yellowstone National Park.