In New Mexico the Continental Divide travels southbound through the western side of the state, following the spine of mountain ranges. On the east side is the Rio Grande, running down the middle of the state, to become the border of Mexico. West of the Divide is Colorado River drainage, and the desert terrain of the Navajo, Zuni, and Arizona, where in places the mountains flatten out, and the Divide is merely the imperceptible high point between here and there.

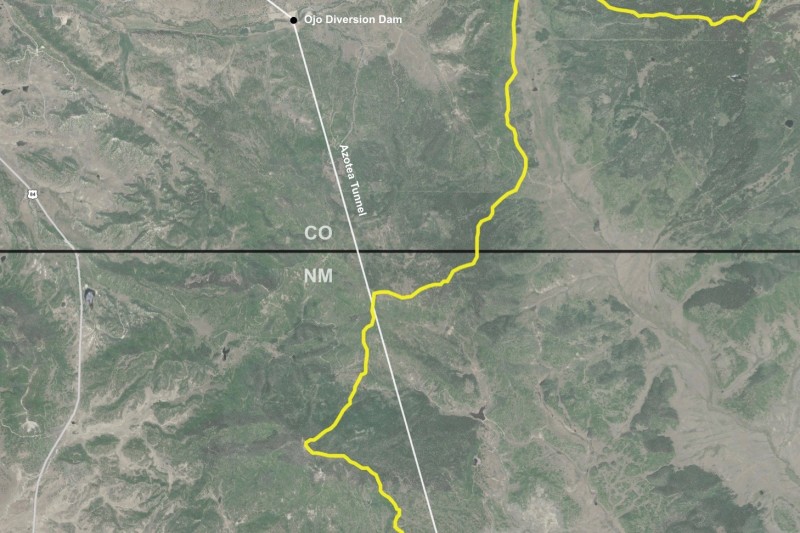

The waters of the southernmost trans-Divide water project, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s San Juan-Chama Project, leaves Colorado and enters New Mexico in the underground Azotea Tunnel, which passes under the Divide a mile south of the state line.

After 13 miles the water emerges from the underground tunnel, and flows through Willow Creek, into Heron Lake, the terminal reservoir for the San Juan-Chama Project, completed in the 1960s.

The tunnel delivers around 100,000 acre-feet per year of water that was once destined for the Colorado River, to the Rio Grande watershed. One acre-foot is 325,857 gallons.

From there the water travels to the El Vado reservoir, part of an earlier Bureau of Reclamation Project. From there it goes on to the Abiquiu Reservoir, then through the Chama River into the Rio Grande near Espanola. The city of Albuquerque is the largest consumer of this water.

The Continental Divide crosses Highway 64 just a few miles from where the Azotea Tunnel passes, invisibly, under the same road.

In much of New Mexico, the Divide is long and low, often barely perceptible.

South of Highway 64, the Divide runs through the Jicarilla Apache Reservation for most of the next 40 miles, and is crossed by Highway 595 a few times, unmarked and likely unknown to most travelers, who are few, as the road peters out into a dirt track.

The Divide is marked where it crosses the busier State Highway 44/550, west of Cuba.

Though the pass is unnamed, and the rise is slight, it is not insignificant.

In addition to a cell tower, there is also a steerable camera mounted on a pole to monitor the highway.

At the base of the pole is the usual State of New Mexico roadside historic marker, with a limited description of the Divide.

The other side of the sign shows some additional unnamed, yet emphatic, points of interest.

The Divide crosses through the Chaco Hills, between Grants and Cuba, 20 miles east of Chaco Canyon.

Near the twin towers of Pueblo Pintado.

On the road the Divide is unmarked and unnoticed.

South of Whitehorse, the road approaches a layered part of the Continental Divide.

At the Divide, the El Segundo Coal Mine, operated by Peabody Energy, is on either side of the road.

Though its extent is not overtly visible from the ground.

From above, the divided strip mining operation on the Divide is much more apparent.

A haul road over the highway at the Divide, uniting the two halves of the mine, adds another layer to this undercutting and surmounting of the Divide.

This mine covers 5,344 acres, and has around 270 employees. It is one of three mines operated by Peabody in the Southwest. The company is more active in the Midwest and in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming, where it operates the largest coal mine in the nation.

Coal leaves the mine by a dedicated railway, seen here where it crosses the Divide again, south of the mine. The mine produces over five million tons of coal a year, which is shipped by rail to power plants in the Southwest.

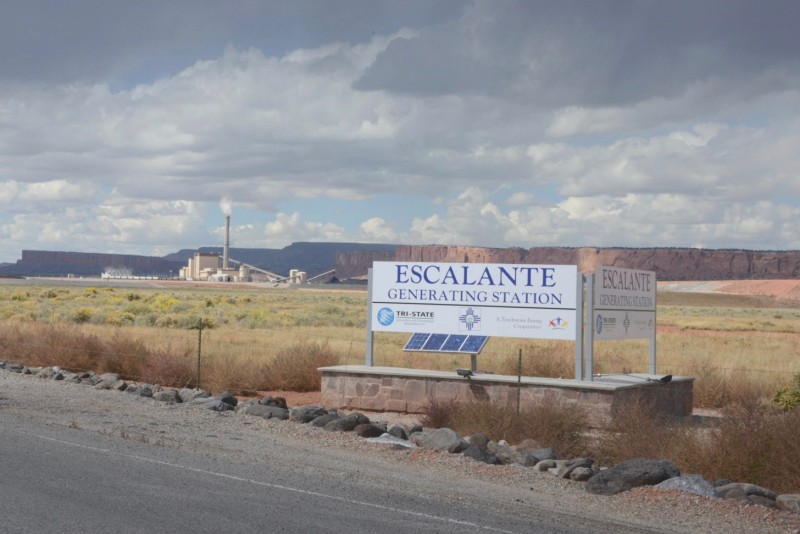

Among them is the Escalante Generating Station, 20 miles south of the mine.

The Continental Divide crosses the road at Borrego Pass, a community centered around the Borrego Pass Trading Post, a traditional Navajo Trading Post established in 1927 and run by white missionaries, in this case Mormons.

There once were around 400 such trading posts in the region, though few operate anymore, and this one was for sale in 2019.

Nowhere is the Continental Divide more celebrated, signified, and visited (intentionally or not), than at the community of Continental Divide, New Mexico.

It is located at Exit 47 of Interstate 40, 47 miles from Arizona, 108 miles from Albuquerque, and between Exit 44 (Coolidge) and Exit 53 (Thoreau).

Signs in the middle of the Interstate mark the Divide at 7,275 feet.

On the service road, it is marked with the usual terse State of New Mexico historic roadside sign.

One sign on each side of the Interstate.

A few residents have an address on Continental Divide Street, in the town of Continental Divide.

Starting in 1926, long before the Interstate, this was Route 66, and remnants of the pre-Interstate roadside abound.

Two gift shops offer American Indian souvenirs, as it is near the Navajo Nation, and Indian lands are checker-boarded around railroad land, state land, and forest land.

The Divide remains united, though elevations may differ.

Before Route 66, emigrant wagons, railways, and early highways came through this way, calling it variously Campbell Pass, Gonzales, and Summit.

A post office makes it official: this is Continental Divide.

The railroad chose this low pass over the Divide for a line connecting Albuquerque to Southern California, in 1880.

It remains one of the principal transcontinental routes for the BNSF.

South of the Interstate, the Continental Divide travels through the Zuni Mountains in the Cibola National Forest, to the base of an old volcano called Bandera Crater.

The crater is one of several in this area that created the massive volcanic flow known as the Malpais Lava Beds, as if the lava flowed out of a crack in the Continental Divide, and flowed towards the eastern drainage before freezing solid, 10,000 years ago.

The lava fields cover a hundred square miles, and in places are nearly impossible to walk on. The region was considered as a place to test the first atomic bomb, but the Trinity site was selected instead, and El Malpais is now a National Monument.

At Bandera Crater, the lava field is wide and deep, but has paths cut through it.

There is a stairwell leading into the ground.

It ends in an ice cave with a fetid pool.

The area is privately owned, and the family that owned it developed it into a tourist attraction in the 1940s, with a small museum, gift shop, and campground.

Next to Bandera Crater Highway 53 crosses the Divide, heading west, while the Divide heads southwest, meandering around forested cinder cones for 20 more miles.

The Continental Divide crosses Highway 60 at an unnamed pass a mile and a half east of the community of Pie Town.

The Divide passes within a mile of a radio astronomy antenna, one of ten similar antennas that form the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), which is the largest dedicated full-time astronomical instrument in the world.

The VLBA is often upstaged by the Very Large Array (VLA), which is another 30 miles east of here. Though the VLA is large, with 27 antennas in a system that is 20 miles across, the VLBA is more than continental in size, with antennas spread across the continental USA, and from the Virgin Islands to Hawaii.

Both are managed by an operations center in Socorro, New Mexico. Their proximity to the Divide is coincidental.

The nearby town of Pie Town apparently did get its name by serving pies to travelers…

…something it still does, including to the occasional Continental Divide Trail hikers who stop in town on their 3,100-mile journey along the Divide.

Another 20 miles west on Highway 60 is Quemado, where the Dia Art Foundation has an office for visitors to Lightning Field, a kind of meteorological minimalist landscape sculpture it owns, that covers nearly a square mile with a grid of 400 steel poles.

Made by the artist Walter De Maria, the sculpture itself is northeast of Pie Town, six miles from the Continental Divide.

The Divide wraps around the west end of the Plains of San Agustin, a flat, empty and arid valley. Its isolation was the primary reason for locating the VLA on its eastern edge. The Divide is crossed by Highway 12.

At the same place, Highway 12 is crossed by the Continental Divide Trail.

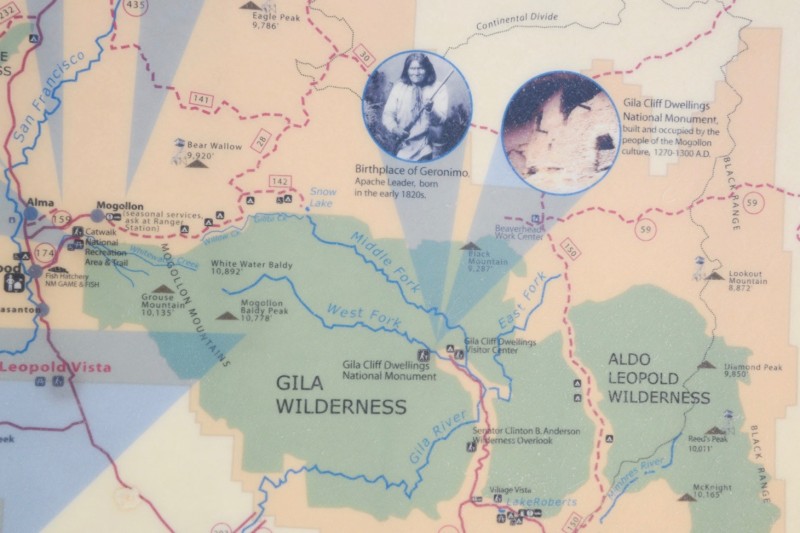

After skirting the southern edge of the Plains of San Agustin, the Divide heads south into the Gila National Forest, a vast remote region covering 3.3 million acres, varying in altitude from 4,500 feet to 11,000 feet. Though much of it is forested, it is desert-like too, and is often steep, crumbly, and desiccated.

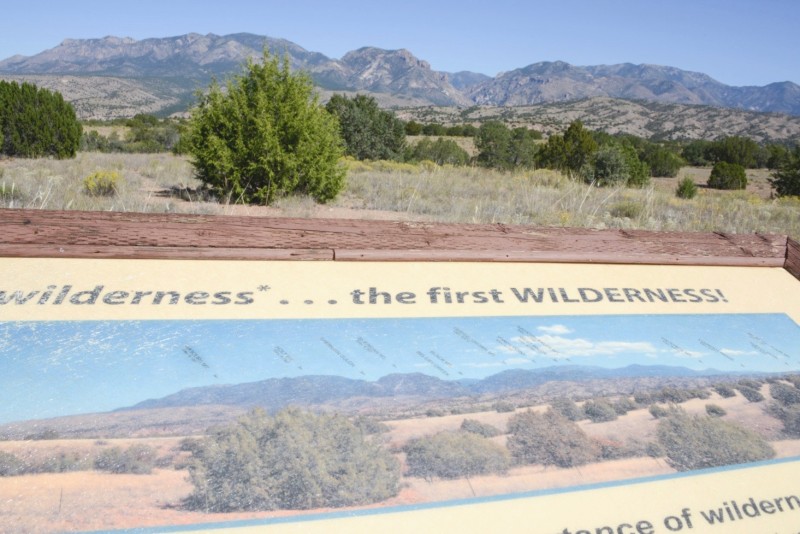

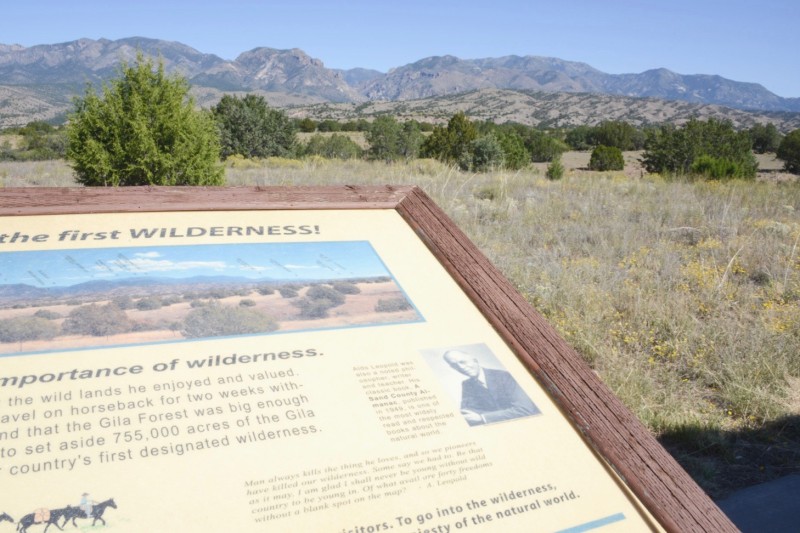

750,000 acres of the forest are designated as the Gila Wilderness, which was the nation’s first official “wilderness” area. It was established by the urging and efforts of the naturalist and writer Aldo Leopold, who served as a forest ranger in the area for periods between 1909 and 1924, often spending weeks alone with his horse.

He was a founder of the Wilderness Society, which believed in the need to preserve places where the land is affected primarily by the forces of nature. He once wrote, “Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?”

Leopold was most famous for the collection of nature essays published in A Sand Country Almanac, which came out in 1949, a few months after he died. A portion of the Gila Wilderness was renamed the Aldo Leopold Wilderness in his honor.

The Federal Wilderness Act, preserving more than nine million acres of federal land, much of it along the Continental Divide, was passed in 1964. It now covers more than 109 million acres, in 750 places, including already established National Parks.

The act defines wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." Mechanized modes of travel are prohibited in official wilderness areas, even bicycles, as well as other machines, like chainsaws and drones, if used by the public.

The Continental Divide travels through the Aldo Leopold Wilderness, on the east side of the National Forest.

It enters civilization again on Highway 35, 20 miles north of Silver City.

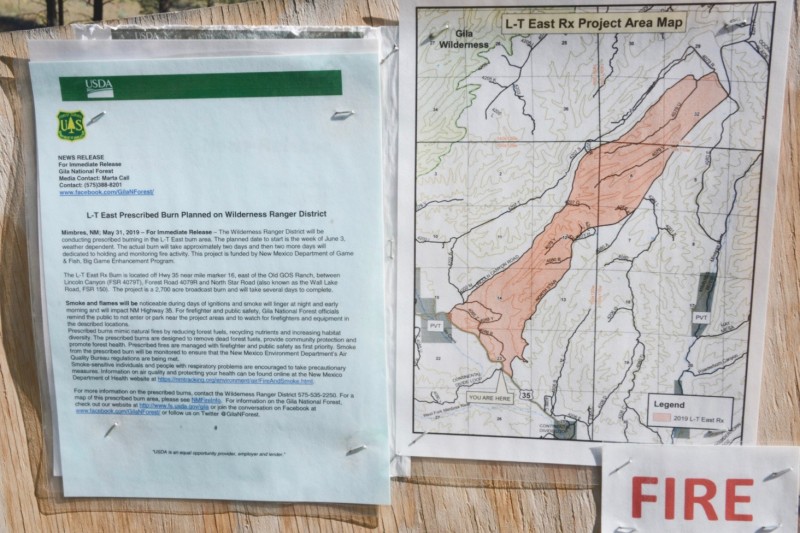

A small road along the Divide leads north into the Aldo Leopold Wilderness.

It is posted as a prescribed burn area.

It's unlikely there are any blank spots left on the map.

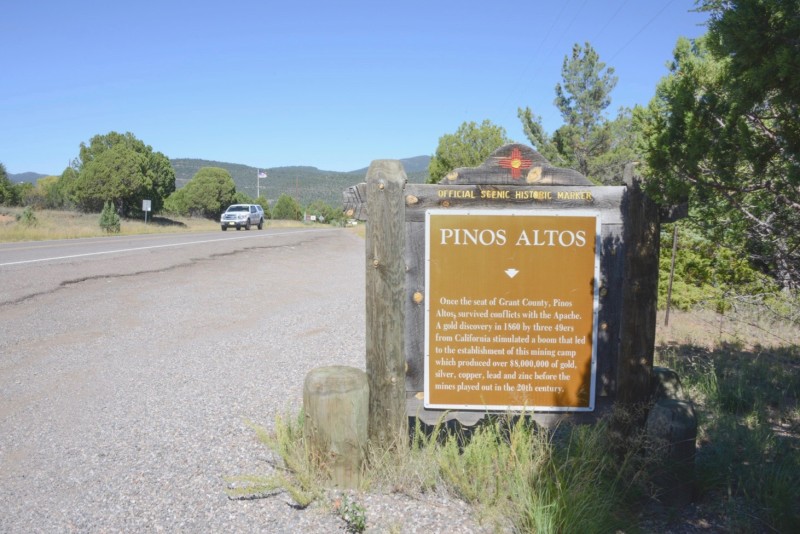

The Divide goes through the community of Pinos Altos, north of Silver City.

It’s the first of several mining areas along the Divide in southern New Mexico.

Not much mining goes on here in Pinos Altos anymore.

It’s primarily a mountain community with inexpensive real estate and tourism.

The Divide goes over Highway 180, just west of Silver City.

With a population of 10,000, the old mining town of Silver City is the largest city for miles. It still has two large copper mines nearby, as well as major reclamation projects.

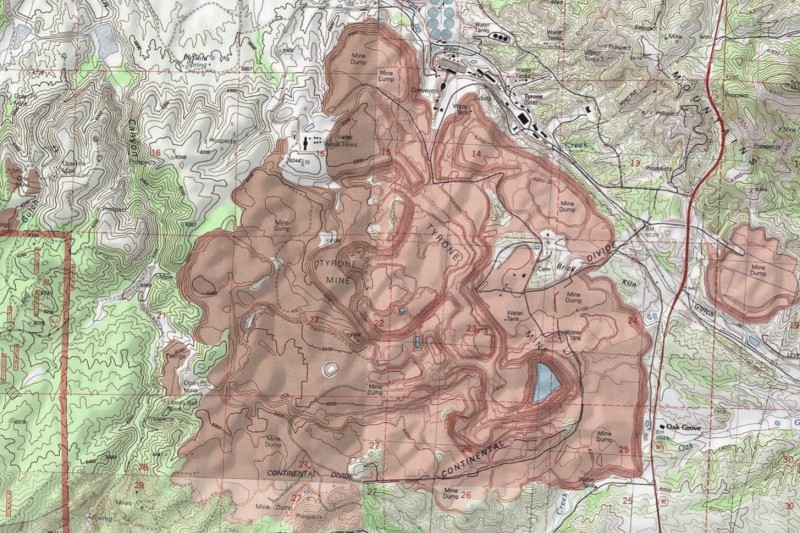

A few miles southwest of Silver City, the Continental Divide enters Freeport-McMoRan’s Tyrone Operations.

This has been an active open pit copper mine since 1967, one of two in the area (the other is the Chino operation, ten miles east of Silver City).

It’s hard to say for sure what happens to the Continental Divide here, though USGS maps still place it on the contours around the mine site as it appeared in the 1980s, when the last map was drawn.

The re-contouring has continued since then.

The map places the Divide on the road to the main entrance to the mine at this point.

Then it goes south into the mining area, meandering around the south side of the operation.

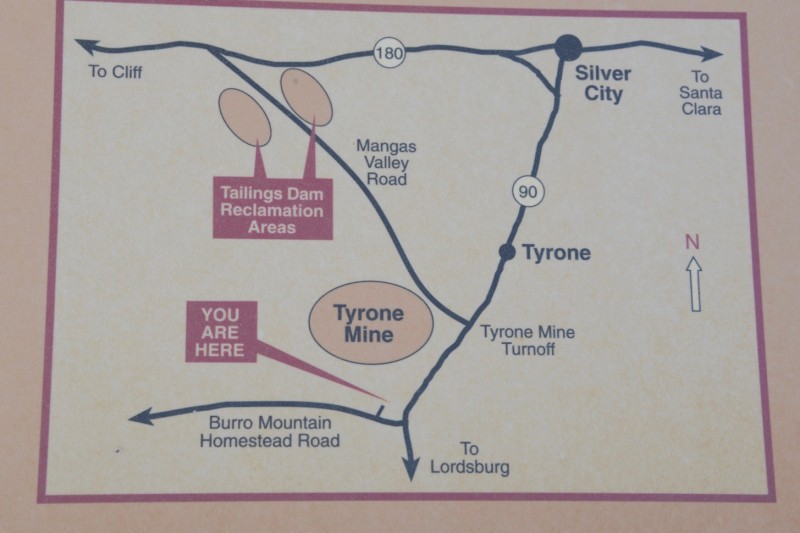

Around the south side of the mound is the Tyrone Reclamation Information Center. Though unmaintained, it still provides an overview of the operations there.

Mining here started a hundred years ago, as an underground operation. The town of Tyrone was built in 1915 by the Phelps Dodge Corporation to house workers for the mine.

The town was designed by noted Gothic and Spanish colonial revival architect Bertram Goodhue, and soon became a very grand ghost town, in 1921, when the underground mine closed. The town crumbled romantically until the 1960s, when the mine opened up again as an open pit operation, and the townsite, now in the way, was demolished.

The mine has operated continuously since open pit operation started in 1967. Phelps Dodge was acquired by the other big Arizona-based mining company Freeport-McMoRan, in 2007. Since 1992, copper has been processed by a solution extraction and electrowinning method, generating around 100 million pounds of copper annually.

Freeport-McMoRan also owns Climax Molybdenum, which operates two major mines on the Continental Divide in Colorado. The company is the single largest sculptor of the landscape along the Divide.

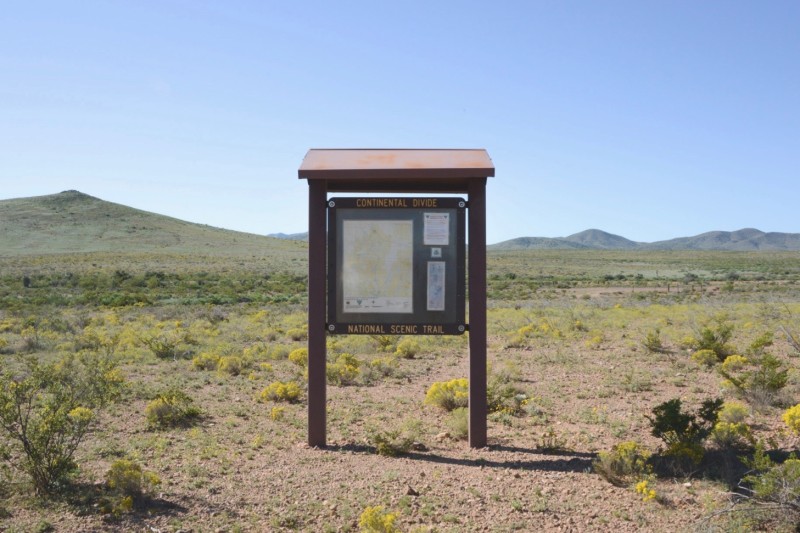

A few miles south of the mine the Divide crosses the highway to Lordsburg, at 6,355 feet above sea level. It’s downhill from here.

Next to it is a newly graded and marked trail site for the Continental Divide Trail. The trail and the true Divide often stray from one another, as the trail stays on public land as much as possible.

From this point south, the trail remains in the hills southwest towards Lordsburg, while the actual Continental Divide follows the original drainage divide to the southeast, out of the mountains and into the desert. Mexico is just 50 linear miles away.

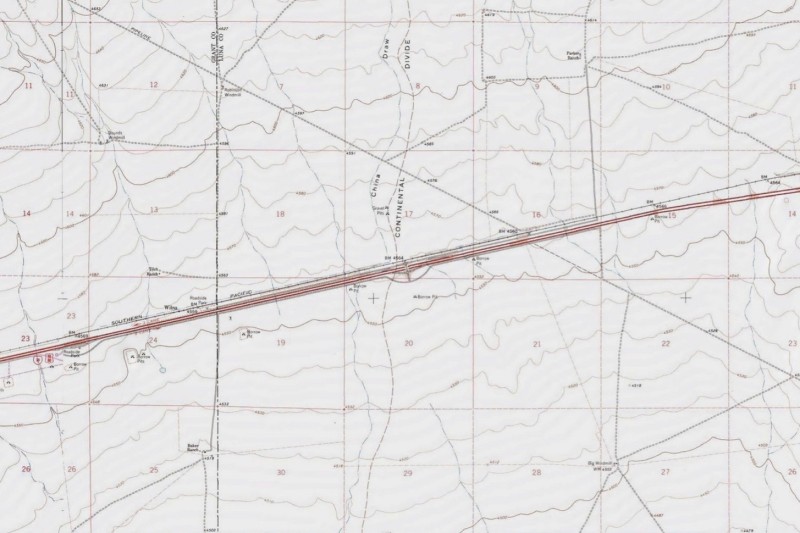

According to the USGS, the Continental Divide crosses Interstate 10 at a point 27 miles west of Deming, and 33 miles east of Lordsburg . . .

. . . at a point near the base of the eastbound offramp of Exit 55.

The highway department, however, marks the site at a point two miles west.

But maybe it doesn’t matter.

It’s pretty flat, either way.

The Southern Pacific Railroad first came through here in the 1880s. The Interstate followed the route 80 years later.

It is one of the busiest mainlines for freight across the Divide, and across the nation, connecting Los Angeles to Texas, New Orleans, and Florida.

The right of way is also used by pipelines and communications lines.

Going in a straight line, one way or the other.

The Continental Divide, meanwhile, meanders south, towards distant hills.

The Divide crosses Highway 146 a few miles north of Hachita.

Then crosses Highway 9 a few miles west.

Then crosses Highway 9 again, a mile west.

Here the Continental Divide meets the Continental Divide Trail.

The trail and the Divide travel together for a few miles, northwest, through the Coyote Hills, though in opposite directions.

Soon the Divide meanders south again, heading towards Mexico, and the trail continues northbound, towards Lordsburg, and Canada. Southbound they will not meet again.

Heading south, the Divide crosses Highway 9 for the third, and last time, and it is the last time the Divide will cross pavement in the USA.

It has reached a new low.

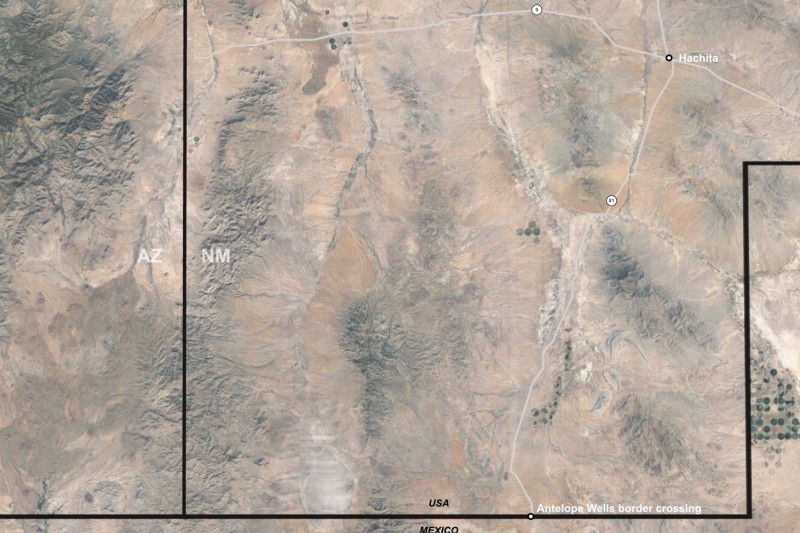

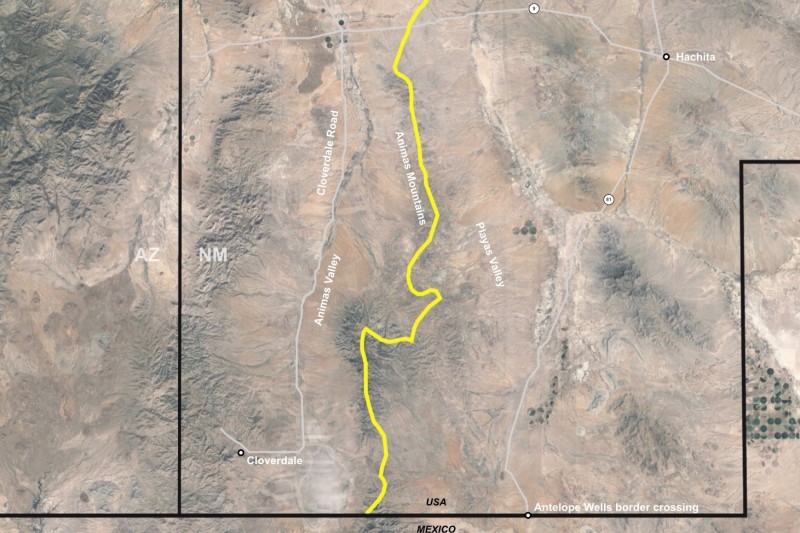

From here the Divide enters the Bootheel – a rectangular tab on the southwestern corner of New Mexico, like an addendum.

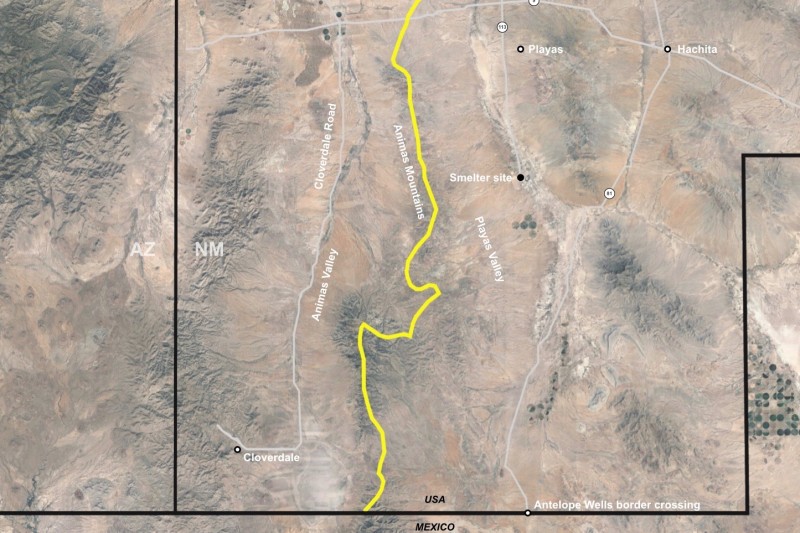

The Divide stays along the crest of the Animas Mountains, with the Animas Valley on the west side, and the Playas Valley on the east side. This is nearly all private land, mostly large private ranches, zealously posted and gated, and crawling with Border Patrol officers.

The road down the Animas Valley dead-ends at the gone ghost town of Cloverdale, five miles before the border.

The road down the Playas Valley passes the former company town of Playas, and dead-ends at the site of a former copper smelter.

Playas was an isolated company town built in the 1970s, to house the workers at a nearby and even more isolated copper smelter.

Now gated and closed to the public, it had more than 270 houses, several apartment buildings, a bowling alley, company store, and other amenities to support a population of more than one thousand.

After the smelter shut down in 1999, the residents left. In 2004, the town was turned into a security forces training facility, operated by New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, a state school in Socorro, and supported primarily by federal funds.

Now called the Playas Training and Research Center, it is a busy site training paramilitary forces.

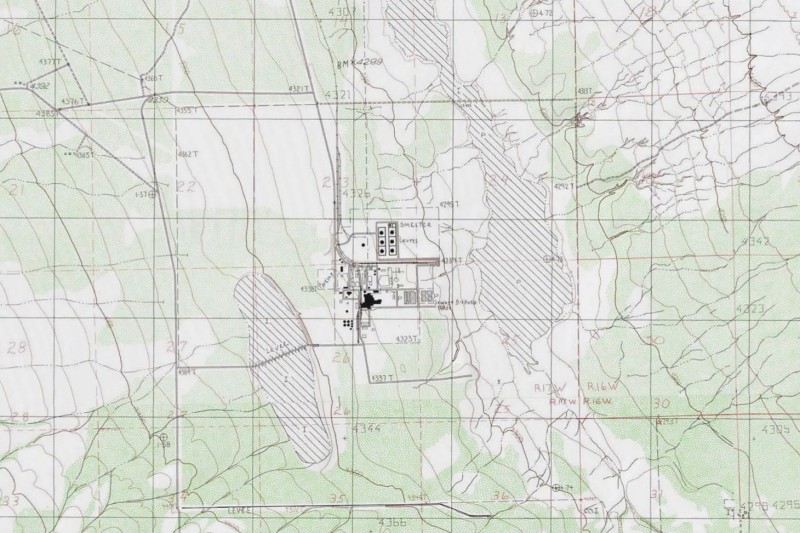

The original residents of Playas worked at Phelps Dodge’s Hidalgo Smelter, ten miles further down the road.

Phelps Dodge opened a copper smelter here in 1971, to process copper from the mines near Silver City, which came by rail through Lordsburg.

The remote site was chosen, as the process was dirty, emissive, and used toxic materials.

The smelter closed in 1999, and has mostly been torn down. Its 600-foot tall stack was toppled in 2007. Remediation efforts including addressing soil and groundwater contamination continue.

Highway 81, south of Hachita, approaches the Playas Valley obliquely, from the northeast, through a pass at Hatchet Gap.

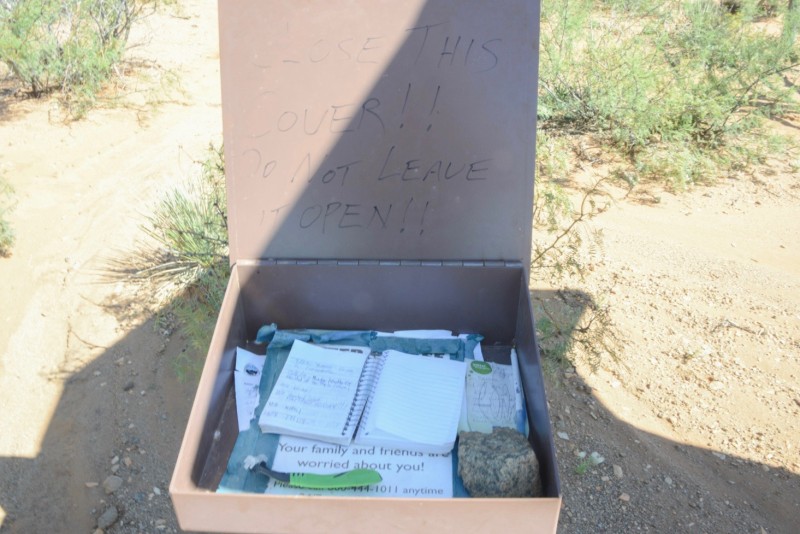

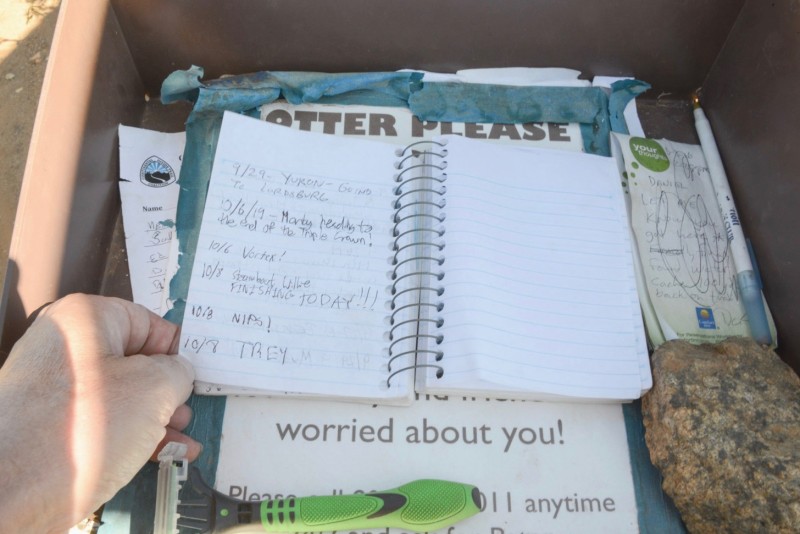

Near the Gap is a kiosk for hikers on the Continental Divide Trail, located at the closest paved road to the southern origin/terminus of the trail.

Most people who hike the entire 3,100-mile long trail, do so from south to north, starting in May and arriving at the other end in September. This avoids the summer heat of the southern part, and gives time for the snow to melt from the peaks.

Southbound hikers start in June, and end up here in October. There is no official way to track how many through-hikers actually make it every year, but it’s likely a few hundred, with the vast majority going northbound.

The trail starts on the border at the Crazy Cook Monument, at the end of a very bumpy and remote road.

South of Hatchet Gap, and just two miles from the border, Highway 81 meets the road to San Luis Pass, a dirt road that goes over the Divide, four miles north of the border.

It once was a county road, and the only connection between the Animas and Playas Valleys, but is now controlled by the landowners, the Diamond A Ranch, which keeps it closed and off limits to the public.

In two miles Highway 81 meets the Antelope Wells port of entry, the only border crossing in the boot heel of New Mexico.

This is the very end of the nation, and the Continental Divide.

Or the beginning, if you are going the other way.