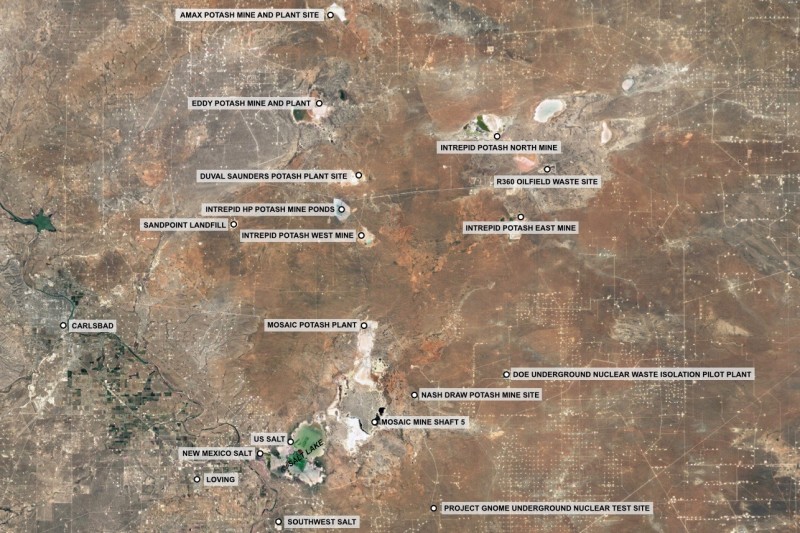

Three mines, producing 80% of the potash in the USA, are in the Carlsbad Basin, in the southeast corner of New Mexico. Potash was discovered here in the 1920s, and underground mining was underway substantially by the late 1930s, when the federal government set aside 43,000 acres to encourage potash mining over other uses. After a boom in production was spurred by demand for explosives in WWII, the Federally Designated Potash Area was expanded to cover nearly 500,000 acres. Over the years mines and processing plants have opened and closed, and mining companies have changed names and ownership. Today two companies own and operate the mines, which have left an interconnected complex of rooms and pillars around 900 feet below the surface, under an area that is around 20 by 25 miles in size.

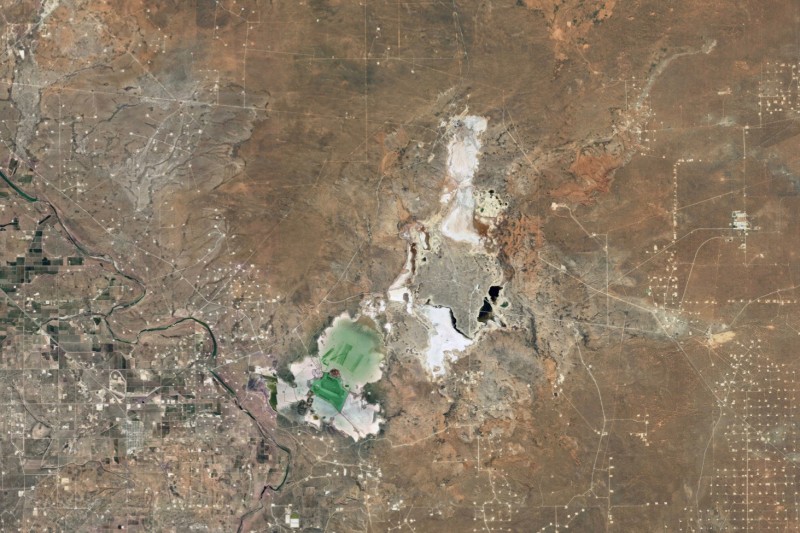

A salt lake named Salt Lake marks the bottom of the basin, where salt crusts cluster into a white expanse.

Brine, pumped from below, evaporates in the sun, leaving salt to be scooped up, washed, dried, and sold by salt companies.

Chlorides of sodium and potassium are often found together in these remnants of ancient seas.

Rocks containing mineable amounts of potash lie beneath and around the exposed lake bed.

The northern end of the lake is inundated with a river of dried tailings, nearly four miles long, extending from a potash plant.

A mineshaft headframe, with gas wells flaring in the distance, is visible across the wastes of Salt Lake.

This is Shaft Number 5, where dozens of people descend every day to operate machines grinding out potash-bearing rock from a horizontal seam 900 feet below the surface, in a vast underground mine, now operated by Mosaic.

There are seven large shafts into this mine. As the front of mining moves onwards, old access shafts become inconvenient. New shafts are made, leaving the old ones behind.

Rocks are ground up inside the mine. Conveyors travel through mine corridors to a processing plant at the north end of the lake, at the head of the plume of tailings.

For decades this plant and mine complex was operated by IMC Global, which is now owned by Mosaic. Based in suburban Minneapolis, Mosaic, the largest US-based producer phosphates, is also the largest US-based producer of potash. This, though, is the only potash mine owned by the company in the USA (most of its potash comes from mines in Saskatchewan).

The mine has been operating since 1940. It extends horizontally underground more than 12 miles from the plant, which sits on top of the main shafts. 700 people work at the plant, and underground, running ten continuous-mining machines, and cutting out langbeinite and sylvite ore from two separate mine layers. This is turned into more than a million tons of potassium fertilizer products annually.

Mosaic’s operation is one of the largest underground mines in the nation, but it is smaller than the other network of mines in the Designated Potash Area. This other network, under the northern part of the Designated Potash Area, has a number of connected mines, most of which are now owned by another company, Intrepid Potash.

Intrepid, based in Denver, is the only US company dedicated solely to producing potash in the USA, and produces more than anyone else, from two mines in New Mexico and two in Utah.

Located a few miles up the road from Mosaic’s plant is Intrepid’s West Mine facility, with two shafts that connect to a mining area with around 13 square miles of under-ground rooms and pillars. Above ground is a plant and a tailings pile covering a square mile.

Opened in 1931 by the American Potash Company, this was the first potash mine in the region, and was owned by the Mississippi Chemical Company when it was purchased by Intrepid in 2004.

Over a period of more than 80 years, the West Mine extracted and crushed sylvite rock, which was turned into muriate of potash (the most common form of potash fertilizer) at the West Plant, and shipped by truck to the nearby North Plant for final processing and storage.

In 2016 Intrepid placed the facility on care and maintenance status, idling mining indefinitely. The site remains active, providing brine to the oil and gas well stimulation operations in the region, and supporting its new solution mining operation nearby.

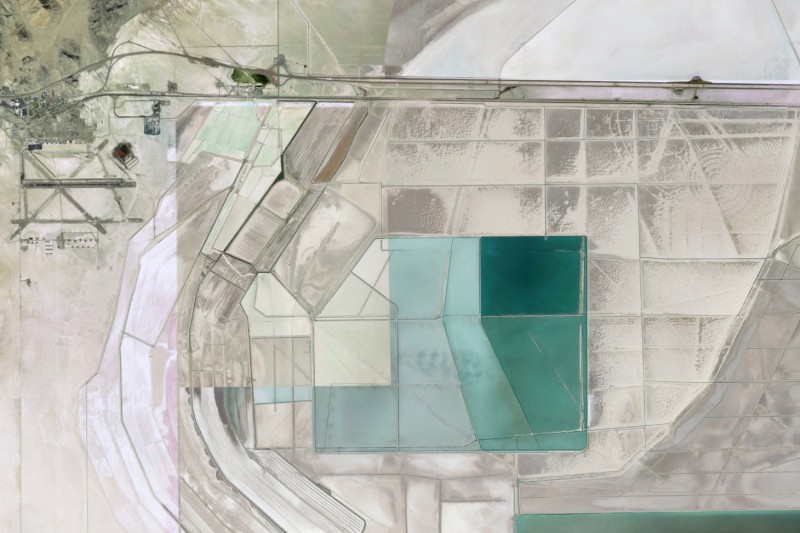

North of the West Mine is a set of evaporation ponds covering a square mile. Intrepid built them a few years ago as part of a new potash mining operation known as the HB Solar Solution Mine, a hydraulic mining operation.

The evaporation ponds hold water that has been pumped through flooded underground mines to dissolve ore from the walls and pillars, to settle and dry out here. After a year or so the dried residue is scraped up and processed into potash fertilizer.

Construction on the HB solution mine project began in 2012, and is costing up to $300 million, as it involves miles of pipelines and other infrastructure, including six injection wells that pump salt water into four disused underground mines, and five extraction wells that pump it out and convey it to the ponds.

The four disused underground mines that are being flushed out include the workings of the Eddy Potash mine and plant, which Intrepid bought in 2004. The plant, which has been abandoned and closed for some time, sits atop a mine, around 1,000 feet down, with several square miles of room and pillar space.

The Eddy Mine is connected to three other underground mines that collectively cover nearly 50 square miles of room and pillar space. The solution mine flushes water through the rooms in portions of these mines, creating underground leach lakes that dissolve pillars that were left to hold up the ceiling, but are no longer needed.

The material scraped from the dried ponds is conveyed as a slurry in a pipeline to a new beneficiation plant at the West Mine site. After filtration, flotation, and dewatering, the potassium chloride is transported by truck to the North Mine facility for further drying, grading, and preparations for sale.

Up to 200,000 tons of potash a year are expected to be generated from the HB Solar Solution mining operation, for a run of 28 years. The company may expand the solution mining operations to cover more of the abandoned mine workings in the region, if all goes well.

The North Mine site is used as a compaction plant and a final processing and storage location for granular muriate of potash from the West Mine and mill, and from the HB solution mine and mill.

Before that, the North Mine site was an active underground potash mine for many years, started in 1956 by the National Potash Company. Intrepid bought the plant and mine in 2004, when it acquired the potash assets of the Mississippi Chemical Company.

The tailings pile covers a square mile, and additional ponds are used to store and process water for the solution mining operations. Beneath the plant site are several square miles of room and pillar mine workings. They extend south under the highway, and connect with Intrepid’s East Mine.

Intrepid’s East Mine is an underground potash mine started by Kerr McGee in 1965. It was part of Mississippi Chemical’s operations when it was purchased by Intrepid in 2004.

The East Mine is the largest of the underground mines in the area now owned by Intrepid. Around 25 square miles of room and pillar space have been excavated, and connect both the North and the West Mines. The working mine walls can be six miles from the shaft sites, and the tailings impoundment and pile cover more than a square mile.

Still a dry mine, with a few hundred people working in the mill and mine, the East Mine stopped producing muriate of potash in 2016, and now focuses on mining the langbeinite ore body layer, which produces a more valuable form of potash with a lower chloride content, favored by higher value crops like citrus, vegetables, and sugarcane.

Intrepid learned about in-situ solution mining, which it applied in the HB Solution Mine project in New Mexico, at its mining complex outside of Moab, Utah.

In 1963 the TexasGulf Company opened Cane Creek, an underground potash mine near Moab, Utah, seeking to diversify from its increasingly obsolete sulfur operations in Texas and Louisiana.

The mine accesses the ore body known as the Paradox Basin, and was converted into a solution mine in 1970, using water from the adjacent Colorado River. Intrepid (Intrepid Oil and Gas Company at the time) bought the mine in 2000, and changed its name to Intrepid Potash.

In 1963, soon after the mine opened, 18 people died in an explosion 3,000 feet below the surface. A memorial was erected by Intrepid in 2014.

The evaporation ponds are located two miles from the plant. The mine workings are between the two, and more than half a mile below the surface. The mine can produce between 75,000 and 120,000 tons of potash annually, depending on evaporation rates, which vary widely, depending on temperature and rainfall.

The ponds are dyed blue to accelerate evaporation.

After purchasing the Cane Creek Mine, Intrepid went deeper and shallower into potash, acquiring underground mines in New Mexico, and surface mining operation in Wendover, Utah.

Wendover’s potash production dates back to WWI, when the Utah Salduro Company extracted potash here from 1917 to 1921. After that operations ceased until WWII.

In 1939 operations began again, expanding into almost 100 square miles of ponds and canals. Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corporation took over operations in 1964. When Intrepid took over in 2004, the mine was owned by Reilly Industries, one of the few remaining family-run chemical companies, which dissolved the following year.

With potash’s chemical connection to salt beds, it makes sense that the Bonneville Flats, the largest and saltiest salt flat in the nation, was among the first places to be commercially mined for potash.

The process involves around 100 miles of ditches, 20 feet deep, dug into the salt flats. With the water table just a few feet below the salty and muddy surface, the ditches immediately fill with water containing the dissolved minerals of the region held in solution. The ditches lead into a central canal, the mother canal, which ends at a pumping station.

The water is pumped into a network of evaporation ponds, first dropping out salt, which is scraped off and sold or dumped. The water moves on to a harvest pond, where it dries from a briny potash slurry, and then is scraped up and taken to the plant where it is crushed, flotated, and dried to become muriate of potash (MOP).

For more than 50 years, the plant has produced between 65,000 and 100,000 tons of potash a year, depending on the weather (especially rain, which dilutes the ponds).

The Bonneville Salt Flats are the exposed bottom of the ancient pluvial Lake Bonneville. East of the flats is the Great Salt Lake, a still-flooded remnant of that ancient lake, and a mineral-rich puddle. This is also mined for potash.

The northern end of the lake is especially salty, as it is largely cut off from freshwater, as a railway causeway divides the lake in half.

The Compass Minerals Company has a pipeline that removes water from the lake here, and pumps it into evaporation ponds next to the lake, in an area known as Clyman Bay.

After the heat and dry air of the region further concentrates the water in this pond, it is released into a canal heading east into the lake.

The canal continues across the lake, underwater, cut into the bottom, and continuously sloping downwards, as it heads eastward. Because brine released from the pond is denser and heaver with salts, it stays inside the canal, flowing slowly–water within water.

The canal, called the Behrens Trench, was built in 1991 by the Great Salt Lake Minerals and Chemicals Company, which operated the salt and potash plant on the lake at that time. It is unique in the nation, if not the world. Dredges keep it maintained.

Taking a week or so to ooze its way to the other side (a distance of 21 miles) the brine is pumped out of the east end of the trench and over the railroad tracks of the causeway, into a more normal canal heading east along the shore of Promontory Point.

And so it flows along the southern end of the point, from one side to the other,

until some of it enters into a perimeter pond, and the rest continues along the shore in the canal,

then heads due east.

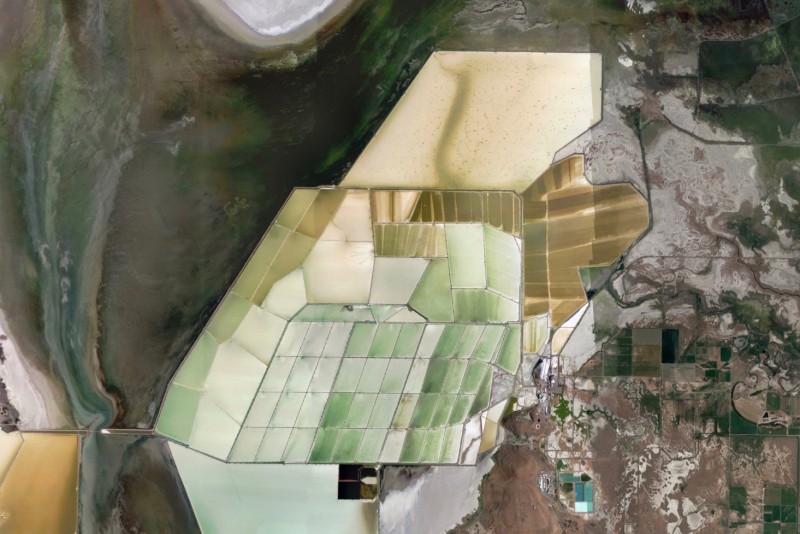

The canal system bringing the brine from Clyman Bay finally ends at the older and larger pond complex at Bear River Bay, next to a potash plant which has been operating here since the late 1960s.

Here the lake brine, with additions from the more immediate waters of the lake, is slowly cooked, allowing colorful algae and bacteria to develop in the ponds, and taking up to two years to reach the right concentration.

The pregnant brine then enters the plant, where it is processed into sulfate of potash, a form of potash fertilizer that is used on high value crops, like fruits and nuts. Much of it is purchased by citrus growers in Florida.

Compass Minerals, based near Kansas City, took over the operation in 2003, and makes around 350,000 tons of sulfate of potash fertilizer here annually. They also produce a couple of million tons of salt, used on roads and in industry.

The two antithetical products, one which helps plants grow, the other which doesn’t, come from the same salty place, and are separated from one another to perform disparate functions, before merging again, eventually, as nearly everything does, in the sea.