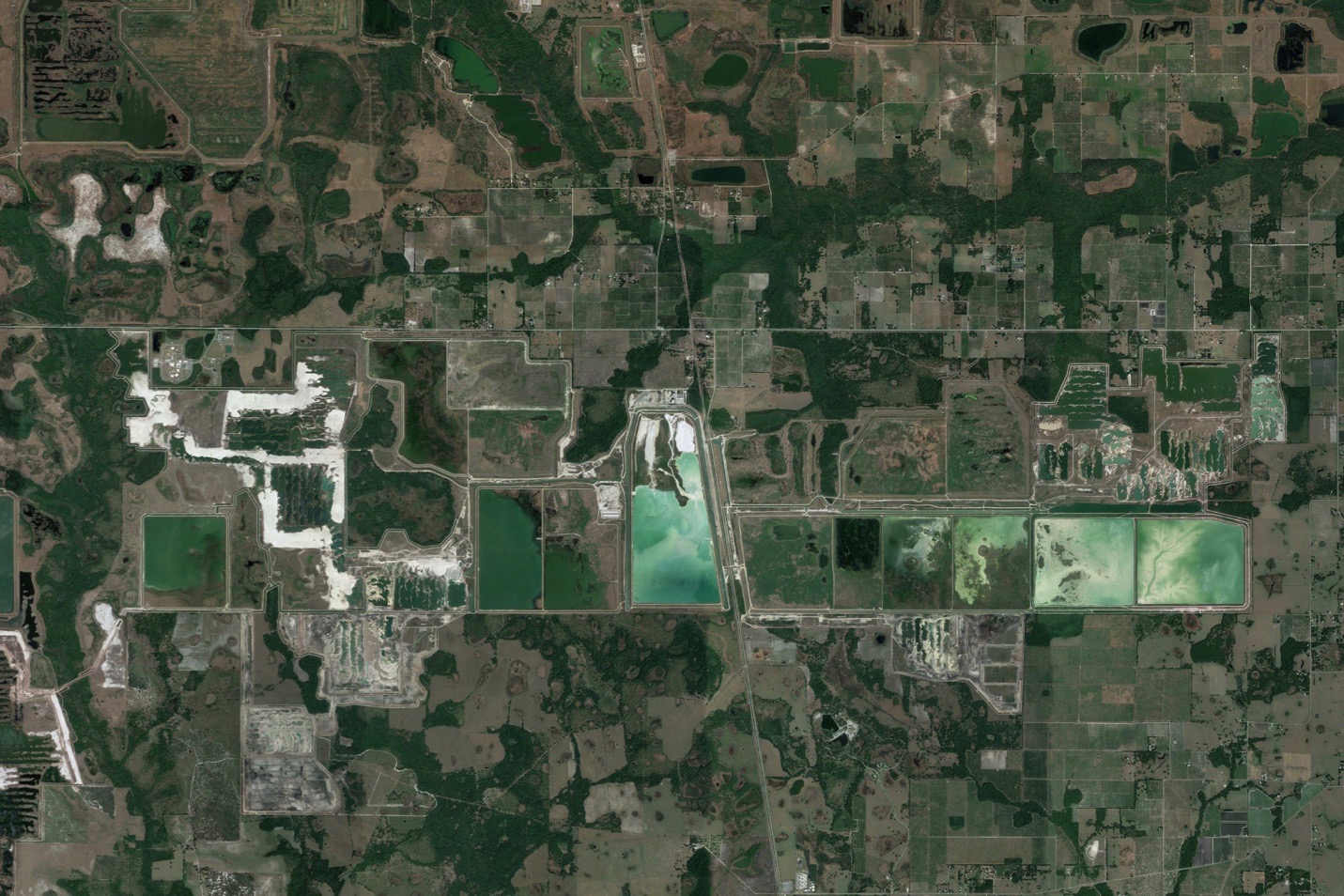

The Bone Valley phosphate formation underlies hundreds of square miles in central Florida, a region that has been transformed by a hundred years of phosphate mining.

Dozens of companies have been active here in that time. Draglines (giant shovels on cranes) are used in strip mining, to uncover the layer of phosphorus rock that lies ten to 50 feet below the surface and to dig it out for further processing into fertilizer.

This being Florida, groundwater is just a few feet below the surface, and the process of extracting the rock is a wet one. Puddles, pools, and ponds of curious shapes are created, making a complex landscape.

Increasingly, reclamation has gotten more organized, and the land is often leveled and reengineered for reuse as tomato fields, golf courses, wildlife areas, recreational parks, and other developments.

Much, however, remains off limits, as the residual effects of phosphate processing leaves chemicals which have to be contained almost perpetually.

Companies that have operated here over the years include ARCO, Agri-Chemicals, Beatrice, Cargill, Conoco, Conserv, Estech, Kaiser, Kerr-McGee, IMC, PPG Industries, the Williams Companies, and CF. After decades of mergers and acquisitions, today the Bone Valley is basically owned and operated by one company, Mosaic.

Mosaic is a new company made up of old companies, formed in 2004 by merging Cargill’s crop nutrition division and IMC Global, both of which were already among the largest fertilizer companies in the nation. Headquarters are in Plymouth, Minnesota, just a couple miles up the road from the headquarters of Cargill, which remains the nation’s largest privately held company. The merger instantly created the largest US-based producer of potash and phosphate fertilizer.

Mosaic owns almost 300,000 acres in the valley, and leases the rest of what it needs, with expansion plans for two more mines in the southern end of a mined and potentially mineable area of 40 by 80 miles.

Mosaic operations officially list two active production plants in the Bone Valley, fed by four active mines; however, the company keeps busy throughout the region, managing dozens of former mines, ponds, tailings piles, plants, and waste sites, covering hundreds of square miles.

The historic center is the town of Mulberry, 30 miles east of Tampa, where mining companies have supported the creation of a phosphate mining museum.

The galleries are inside old railroad cars, and have colorful displays about the industry.

A more conventional museum display is located in an adjacent building, which showcases the fossils that have been found in the process of unearthing so much earth. The chemistry of the phosphate deposit, created by ancient seas, preserves fossils well, which explains the region’s name, Bone Valley.

Mosaic’s Four Corners Mine is the largest of its four active mines, producing 6.4 million tons of phosphate rock in 2017 (out of a total of 15 million tons produced by the company globally). The mine covers 12,000 acres, and employs around 500 people. It is one of four similar Mosaic operations in the Bone Valley.

Each mine is really a network of surface excavation areas, overburden storage, water retention ponds, berms, ditches, pipelines, pumping facilities, and preliminary processing plants.

The first step in the mining process is to dig trenches and berms around the immediate area to be mined, so that some of the groundwater drains into the perimeter ditch, keeping the mining area from becoming more of a mud puddle than it already is.

Then draglines remove the sandy soil that covers the ore body, some ten to 50 feet below. Mosaic has around 20 draglines in the area, and is using eight of them at the Four Corners mine. The company says they are the largest earth-moving machines on the planet. They run on 72,000 volts of electricity, and have two operators.

After the outer layer of overburden is moved to the side, draglines extract the ore body, known as the matrix, which is around 1/3 clay, 1/3 sand, and 1/3 phosphate rock. Each scoop of matrix is dumped in a pool, where high-powered steerable water-jets break down the material into a slurry. The slurry goes in a 20-inch pipeline to the beneficiation plant.

Each mine site has a beneficiation plant, a large facility, which, by washing, screening, flotation, and other means, separates the sand, clay, and ore. The sand is stored until it is used for filling in mine pits, and the clay goes to clay ponds, as a slurry.

The clay ponds are generally around a square mile in size, and grow to be 40 to 50 feet tall, as more and more clay is deposited. The water leaches out of the clay into pipes controlled by a valve at the bottom of the pond. The clay ponds are also used to store water, which helps keep dust down.

The phosphorus rock material, separated and dried at the beneficiation plant and in granular form, is shipped from Four Corners by train to processing plants elsewhere, to be turned into fertilizer products.

Mosaic’s South Fort Meade Mine is currently the second largest of Mosiac’s mines, producing 4.4 million tons in 2017.

Mosaic’s South Pasture Mine is the third largest of its four active mines, producing 2.8 million tons in 2017. It is one of a few phosphate mines and plants that Mosaic acquired from CF Industries in 2014, when CF sold its phosphate and potash facilities, to focus on nitrogen.

The fourth active Bone Valley mine, Mosaic’s Wingate Creek Mine, produced 1.4 million tons in 2017.

Unlike the others, the Wingate mine has been allowed to flood, and Mosaic uses dredges to remove overburden and mine the ore.

Phosphate ore processed at beneficiation plants at the mine sites is moved by rail and pipeline to production plants, one of which is Mosaic’s Bartow facility.

The initial material produced at Mosaic’s plants is phosphoric acid, which is created by combining processed phosphate rock with sulfuric acid. Sulfur for creating sulfuric acid comes to the plants by rail or truck from oil refineries, where it is an abundant byproduct. Mosaic owns a sulfur terminal in Houston (for shipping sulfur) and another at Tampa (for receiving it).

The principal finished product produced at these plants is diammonium phosphate (DAP), which is made by combining phosphoric acid with anhydrous ammonia. This combination produces slurry, which is pumped into a granulation plant and mixed with more ammonia to produce DAP, a solid granular product that is applied directly or blended with other solid plant nutrient products such as urea (N) and potash (K). It takes more than 1.5 tons of phosphate rock to make one ton of DAP.

Bartow and most other Mosaic plants also produce monammonium phosphate (MAP), which is similar to DAP, but has more phosphorus. The plants also produce a bulk fertilizer product called MicroEssentials, an ammonium phosphate product with additional micronutrients, like sulfur and zinc.

The Bartow Plant produced 2.2 million tons of processed phosphates (DAP, MAP, MicroEssentials) in 2017, out of a company-wide total of 9 million tons. Over that time it also produced a million tons of phosphoric acid, out of a company-wide total of 5 million tons, which is about 10% of world production, and 60% North American production.

Mosaic’s New Wales Plant, near the town of Lithia, is the second of two fertilizer production plants currently operating in the Bone Valley.

It's output is higher than Bartow's: in 2017 it produced nearly 3 million tons of processed phosphates, and 1.4 million tons of phosphoric acid. It also produces animal feed products.

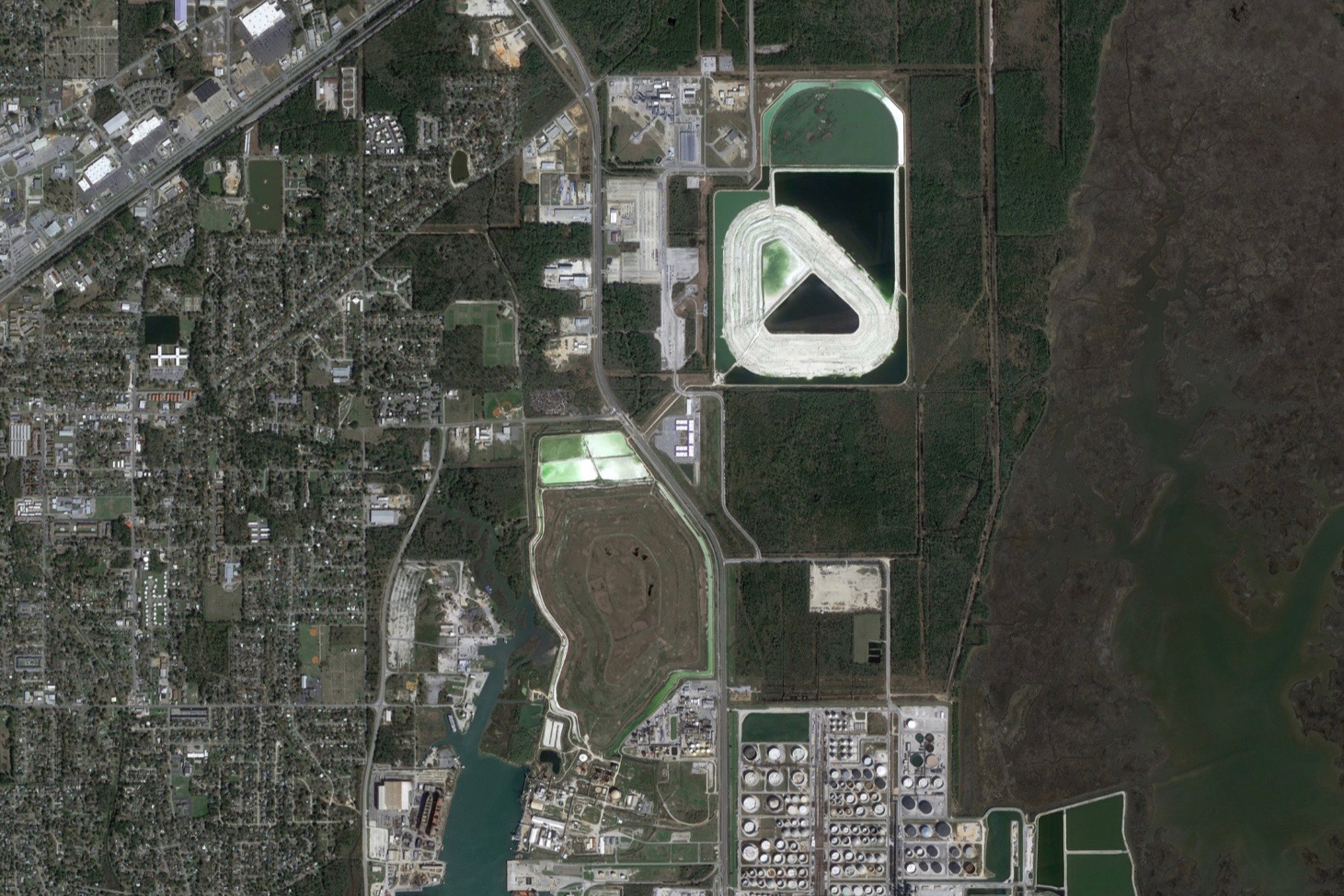

When phosphate rich ore is mixed with sulfuric acid to make phosphoric acid, it produces phosphogypsum as a byproduct, which is piled high at these plants in a waste mound known as a gypstack. The material arrives as a slurry, and a liquid pond is usually present at the top of an active gypstack.

In 2016, a sinkhole formed under one of the two cells in the active gypstack at the New Wales Plant, causing process water to drain into the sinkhole. Close to $100 million has been spent to fix the problem.

Mosaic’s Plant City Plant is a bit of an outlier, located by itself north of the rest of the Bone Valley mines and plants. Since 1965 it has been operated by CF Industries, until it was purchased by Mosaic in 2014.

At the end of 2017, after it had produced more than a million tons of processed phosphates and more than half a million tons of phosphoric acid that year, Mosaic announced it was idling the plant for at least a year.

Mosaic shut down its South Pierce Plant in 2006.

Like the others, it produced phosphoric acid. The plant remains as a potential resource, to reopen or use for parts, and as a remediation and environmental monitoring site, for decades to come. Bone Valley has dozens of permanently closed phosphate operations, many of which are part of Mosaic’s assets and responsibility.

The Bonnie Mine and Plant was a major phosphate site that closed in 1999, and is now primarily an environmental monitoring location for the former plant site and waste ponds.

Mosaic has leased parts of the old plant site to other companies to use as a storage terminal for bulk materials associated with mining and fertilizer activity.

The former Royster Mine is another old mine site that is being maintained and partially redeveloped. It is immediately adjacent to the town of Mulberry.

Mosaic’s Lonesone Mine has been closed for a while, with active mining moving south and east to the Four Corners Mine.

The landscape remains churned up in the mining areas of Fort Lonesome. Former phosphate mines can be found westward towards Tampa, with increasing amounts being redeveloped into housing areas.

Though mining stops a few miles from Tampa Bay and the City of Tampa, the handling and processing of phosphates occurs around the shore, especially at Mosaic’s Riverview Facility on Tampa Bay.

The plant is similar to the two operating in the Bone Valley, a few miles east, and produces 800,000 tons of phosphoric acid and 1.6 million tons of processed phosphate (primarily DAP and MAP) from phosphate rock extracted in the valley.

Like the other plants, Riverview stacks its main waste product, phosphogypsum, in a mound next to the facility, making a gypstack that covers more than a square mile.

Mosaic’s Tampa Marine Terminal is a storage and shipping facility at the Port of Tampa Bay, used for the export of DAP and MAP, the two primary phosphate fertilizers it produces at its three active central Florida plants. From here the material is shipped by barge around the Gulf Coast, and up the Mississippi to the corn belt and other agricultural areas.

Mosaic's Big Bend Marine Terminal, in Gibsonton, is another terminal on Tampa Bay, with rail, truck, and ship access, used to handle bulk phosphate rock and finished phosphate fertilizers.

Mosaic uses facilities at the port to receive and store the large amounts of anhydrous ammonia it needs to make phosphoric acid and other products at the plants. One of these is the Hookers Point Terminal, acquired from CF Industries, with a 38,500-ton ammonia storage tank and a deep water dock.

The terminal is connected to a 75-mile underground pipeline system that delivers ammonia to the Riverside Plant, and to the other plants in the Bone Valley. Ammonia is normally a gas, so it is kept pressurized in order to condense into liquid form for storage and transport. Around 2 million tons of ammonia comes into the Port of Tampa in this form every year, to feed Mosaic’s production.

The ammonia comes by tanker ship from Mosaic’s Faustina plant, its ammonia production facility at Donaldsonville, Louisiana, and from other nitrate companies, like CF Industries, also in Donaldsonville.

The Faustina facility also delivers ammonia directly via pipeline to its Uncle Sam plant, located on the other side of the Mississippi River. Uncle Sam turns the ammonia into phosphoric acid, which it sends back, via pipeline, to Faustina to turn into diammonium phosphate fertilizer (DAP).

The Uncle Sam facility was originally owned by Freeport Chemical Co., and then by IMC Global, which merged with Cargill’s crop nutrition division to form Mosaic in 2004.

Like other phosphate fertilizer production sites, the Uncle Sam plant has a phosphogypsum stack, more than a square mile in size, behind the plant. Together Mosaic’s gypstacks in Florida and Louisiana contain an estimated 60 billion pounds of hazardous waste, along with billions of gallons of acidic wastewater. With pressure from lawsuits, the EPA, and state governments, the company has recently agreed to develop a $2 billion fund to address the problem.

Mosaic is not the only phosphate fertilizer company working in Florida and Louisiana. Though it is more prolific in its production of nitrogen and potash fertilizer products, Nutrien is the second largest phosphate fertilizer production company in the USA. It operates two mining areas, one in Florida, and the other in North Carolina, as well as one in Canada, where the company is based.

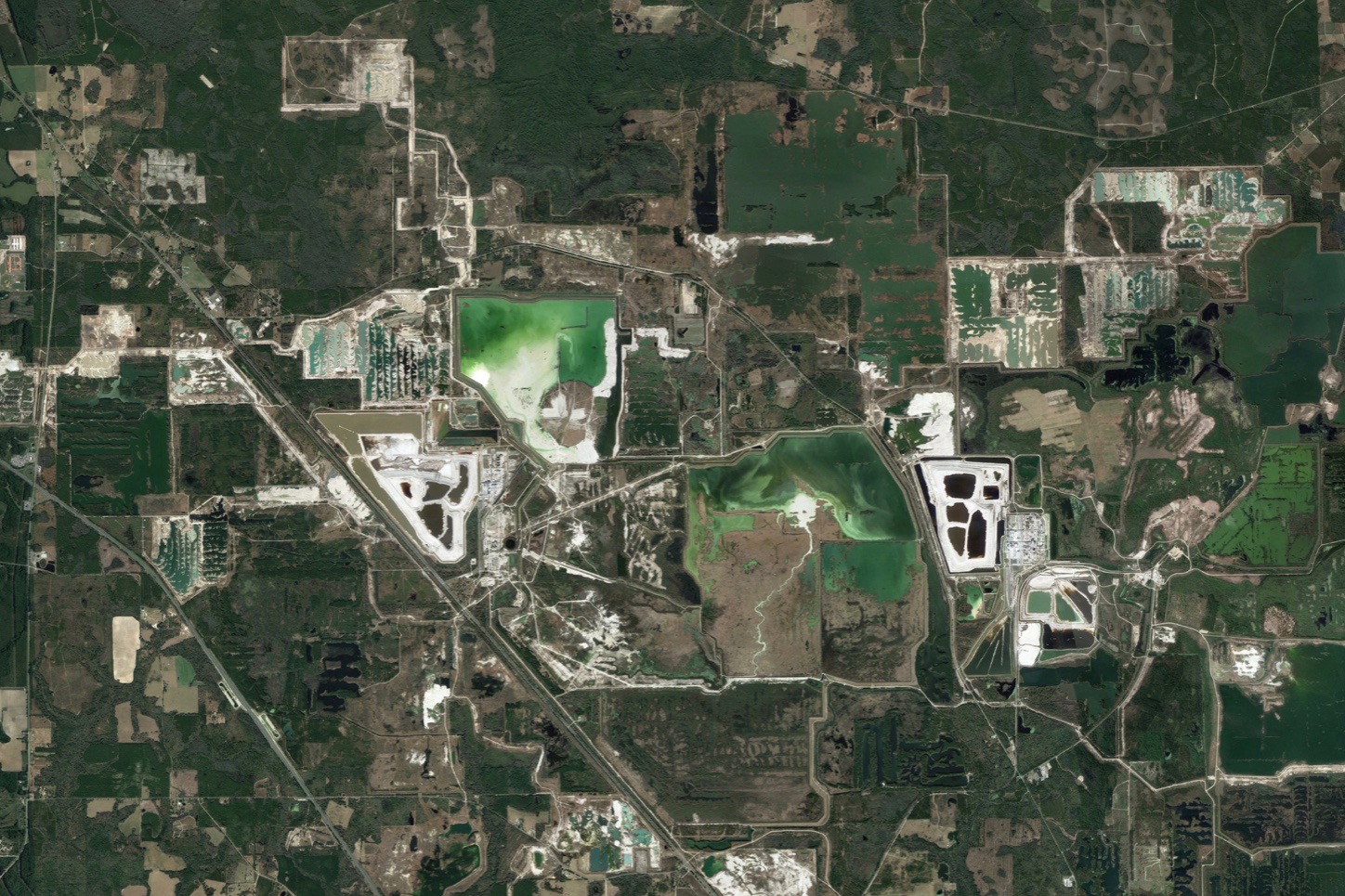

Nutrien’s Florida operations are in the northern part of the state, near the border with Georgia, and cover a ten by ten square mile region around White Springs, most of which has literally been turned over by years of strip mining phosphates. The region has two principal production complexes within it.

The westernmost of the two complexes is the White Springs Swift Creek Complex. This facility was operated by the Potash Corporation until 2018, when Nutrien was formed by the merger of the PotashCorp and Agrium.

Like Mosaic’s process in the Bone Valley, Nutrien uses large draglines to remove overburden and dig out the ore, which is sent by slurry pipes to screening and sorting plants, then to production plants where sulfuric acid turns it into phosphoric acid and then into dry phosphate fertilizer products.

The eastern portion includes the White Springs Suwanee River Chemical Plant, also formerly owned by the Potash Corp.

The construction of the plants, and most of the mining, was conducted by the Occidental Petroleum Corporation of Los Angeles, which started phosphate mining here in the 1960s. PotashCorp bought the operation in 1995.

Nutrien is also the new owner of PotashCorp’s phosphate mine and plant in Aurora, North Carolina.

Not as vast as the northern Florida site, the Aurora operation, measuring six miles by six miles, is large enough to be called the largest integrated phosphate mining and chemical plant in the nation, since it has just one plant, surrounded by its mines and waste ponds and piles.

The mine produces around 5 million tons of phosphate ore a year, which the plant turns into around one million tons of phosphoric acid.

The phosphate deposit here was discovered in 1955, and was developed primarily by the TexasGulf company, known for its sulfur mining operations in Texas. PotashCorp bought it from TexasGulf in 1995.

The mine and plant are located on the Pamlico River, and barges move most of its material to market through the deep water port at Morehead City, or by rail directly from the plant.

When it came into existence in 2018, taking over the assets of PotashCorp, Nutrien acquired this combined phosphate and nitrogen fertilizer complex in Geismar, Louisiana.

It is located in a chemical complex on the Mississippi River, sharing the site with an Innophos phosphate chemical plant, Honeywell Specialty Materials, and Nova Chemicals, with a phosphorous gypstack at the back of the complex.

In addition, Nutrien now operates several other former PotashCorp phosphate fertilizer facilities that further refine and blend products, including this upgrading plant in Joplin, Missouri,

the Marseilles Phosphate plant, on the Illinois River, west of Chicago,

and the Weeping Water Phosphate plant in Nebraska.

By absorbing Agrium, Nutrien also inherited a few phosphate granulation plants, including the Americus Rainbow Granulation Facility in Georgia,

and the Florence Rainbow Granulation Facility in Alabama, across the river from the government’s historic fertilizer development center at Muscle Shoals.

There is another cluster of phosphate mining and fertilizer production in the western United States, where a Permian-age sea bed deposit known as the Phosphoria Formation is mined.

The mines are centered around a remote corner of southeastern Idaho. More than 30 mines have operated over the last century. Today there are only a half dozen or so active mines, operated by a few different companies, and they are small and scattered compared to the operations in Florida and North Carolina.

Itaphos, a Canadian phosphate fertilizer company, based in the Cayman Islands, recently acquired some of the mines in the area from Agrium. Regulators required Agrium to divest itself of some of its phosphate assets in order to join with the PotashCorp to become Nutrien.

These mines supply the nearby Conda Phosphate Operation, a former Agrium plant, previously owned by Simplot for many years before that.

The Conda Phosphate Operation produces approximately 540,000 tons per year of mono-ammonium phosphate, super phosphoric acid, merchant-grade phosphoric acid, and other specialty phosphate products.

The Blackfoot Bridge Mine is the latest mine to be opened in the region by Monsanto, which has mined the area for many years in order to supply its phosphate plant in Soda Springs.

Monsanto’s phosphate plant has been operating since the 1950s, and is a functioning superfund site, producing elemental phosphates used for foods, chemicals, fertilizers, and the company’s signature herbicide, Roundup.

Monsanto, based in St. Louis, is one of the largest and longest-lasting agrochemical companies in the USA, notorious in more recent times for genetically engineering crops controlled by its branded herbicides. In June 2018, the company was officially sold to Bayer, the German life sciences corporation, which announced that it would be discontinuing the use of the Monsanto name.

Despite the end of the “Monsanto” name it is expected that the plant will continue to operate, with around 400 employees, as its capacities are unique. It will certainly have to be maintained as an environmental management site for a while to come.

Over the years its gypstack has been a local attraction, as cauldrons of glowing molten tailings can sometimes be seen being dumped over the edge of the continuously growing mound, and flowing down like lava.

For more than 50 years, the FMC plant in Pocatello was the largest elemental phosphate plant in the USA, and was fed by local phosphate mines, until it was torn down in 2001. The site is now a series of closely monitored gypstacks and waste piles, some of which contain the remains of the buildings and chemical rail cars.

Next to the FMC plant site in Pocatello is the Don Plant, a large functioning phosphate plant operated by Simplot, with a growing black gypstack behind it.

The plant has been operating since 1944, when it was the first fertilizer production facility built by the J.R. Simplot company. Much larger now, it produces more than a million tons a year of phosphate fertilizers, feed phosphates, and industrial products, and employs around 350 people.

The Don Plant consumes around 400,000 tons of sulfur annually (which comes by rail), to generate sulfuric acid. The sulfuric acid is mixed with phosphate ore to become phosphoric acid, which is then mixed with ammonia to produce ammonium phosphate, the basic form of fertilizer, and source for more complex fertilizer and phosphate products.

The Don Plant consumes around 1.7 million tons of phosphate ore annually, which comes from its Smokey Canyon Mine, in southeast Idaho, next to the border of Wyoming.

The mine was developed in the mid-1980s and has a beneficiation plant on site, which refines and grinds the ore into a powder. It is then mixed with water and moved via an eight-inch-diameter pipeline to the Conda Plant, 27 miles away, which was owned by Simplot when the pipeline opened.

In 1991, a booster station was installed at Conda, and the slurry pipeline was extended to the Don Plant, 60 miles away from Conda, and 86 miles from the mine. This pipeline continues to be the sole source of phosphate ore for the Don Plant.

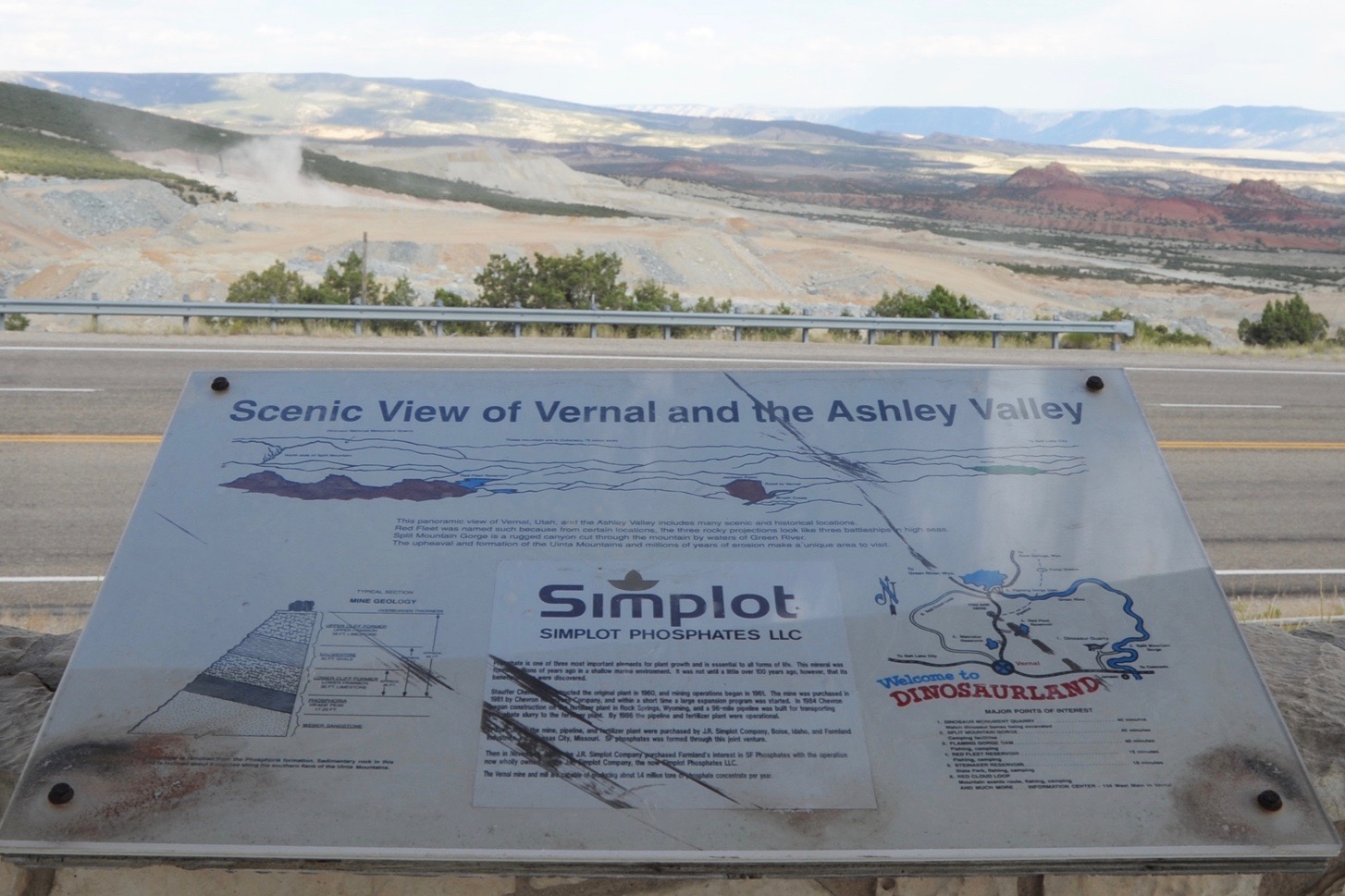

The Don Plant is the largest of four fertilizer plants operated by J. R. Simplot. The second largest is an isolated facility outside of Rock Springs, Wyoming, where the company makes monoammonium phosphate (MAP), as well as phosphoric acid.

The Rock Springs plant was built by Chevron in the mid-1980s, and was taken over by Simplot in 2003. The company recently built a $300 million ammonia plant at the site, which supplies the Don Plant with ammonia too.

The phosphate ore for the Rock Springs Plant comes from a mine north of Vernal, Utah, and is conveyed to the plant through a pressurized slurry pipeline 96 miles long.

The mine was originally developed by the San Francisco Chemical Company in 1960. It was purchased by Chevron in 1981, which built the slurry pipeline and the Rock Springs plant around 1985.

Simplot operates two other smaller fertilizer plants, neither of which is near a mine. They are located in the midst of agricultural production in the central valley of California. The plant in Lathrop is at the north end of the valley, near the port of Stockton, and produces a variety of ammonium phosphate fertilizer products directly to local agricultural suppliers.

The second smaller fertilizer plant is in Helm, in the southern end of the valley, which primarily provides ammonium nitrate fertilizer to local agricultural suppliers.

Other companies manufacture phosphate fertilizer products, using raw materials from other suppliers, sometimes at industrial plants originally built by other, larger companies that have since moved on. In Lawrence, Kansas, for example, a former FMC phosphate products plant is now operated by the Israeli company ICL Performance Products.

The company also has another plant at Carondelet, Missouri, which was formerly operated by Monsanto. ICL makes fertilizers, food products, and engineered materials, based from its origins as an Israeli company extracting minerals from the Dead Sea.

Scattered around the country are a number of former phosphate plants in limbo, or orphaned in decay, like the Mississippi Phosphates company site in Pascagoula, Mississippi. Diammonium phosphate fertilizer was produced here from the 1950s to 2014, when the company went bankrupt.

The $12 million fund that had been set aside to address the remediation quickly ran out. Two phosphogypsum stacks ceased to be managed, and millions of gallons of acidic liquid wastes flowed into the bay. The site now has superfund status, and the state and the EPA are addressing it.

There are many such places, including more than two dozen active and inactive gypstacks in the Bone Valley of Florida, and more in Louisiana, Texas, and the Midwest. Many are overgrown, abandoned by the dissolved companies that made them.

Nowhere more so than here, in Pasadena, Texas, outside Houston, where gypstacks from decades of phosphate fertilizer production create a range of toxic geometric hills and dales in the petro-chemical heart of the nation.