Yards Creek is a 450-megawatt pumped storage operation in the Appalachian Mountains in northwestern New Jersey.

It has an upper and lower reservoir separated by 3,600 horizontal feet, and 700 feet in elevation.

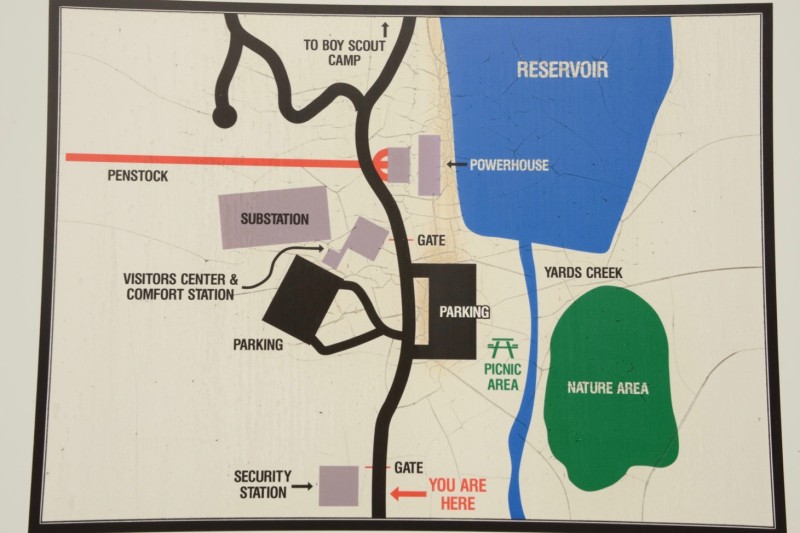

An 18-foot diameter pipe carrying the water up and downslope emerges from underground halfway down the hillside, and splits into three penstocks that connect to three pump/turbines in the plant, which is located on the lower reservoir.

The facility is owned by PSEG, an electric and gas utility company based in New Jersey, and FirstEnergy, a regional energy transmission company.

Though a visitor center and comfort station appear on a map of the facility at the gate, they have been closed for years, and the grounds are not open to the public.

It has no interpretive or public facilities. Other than the gate at the main entrance, the closest the public can get is along the Appalachian Trail, which passes by the upper reservoir near the top of Kittatinny Ridge.

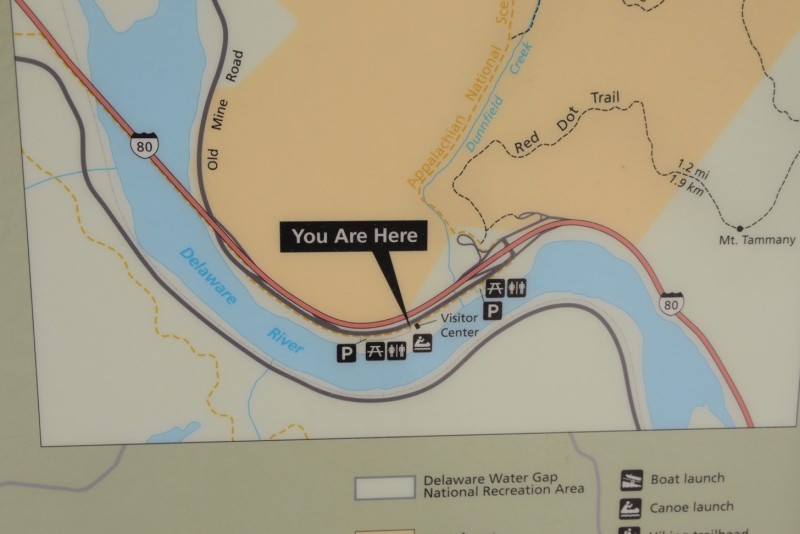

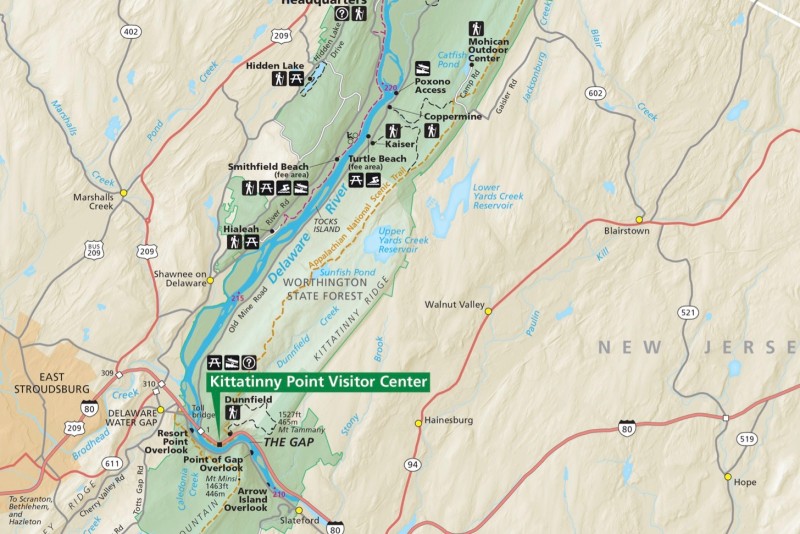

The Yards Creek project is near the Delaware Gap, where the Delaware River cuts through the mountains at Kittatinny Ridge.

The project is a remnant of a larger project proposed for the region in the 1960s, which would have included the largest dam east of the Mississippi along the Delaware River, upstream of the Gap, and a few more storage reservoirs along the ridge near Yards Creek.

The controversial project was canceled in the 1970s, but after the government had acquired 70,000 acres of land and displaced more than a thousand people by eminent domain.

The land was turned over to the National Park Service, and became the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, a park that extends for forty miles up the river from the Gap.

The Yards Creek pumped storage project was completed in 1965, long before the park existed, on private land, owned by the utility that operates it.

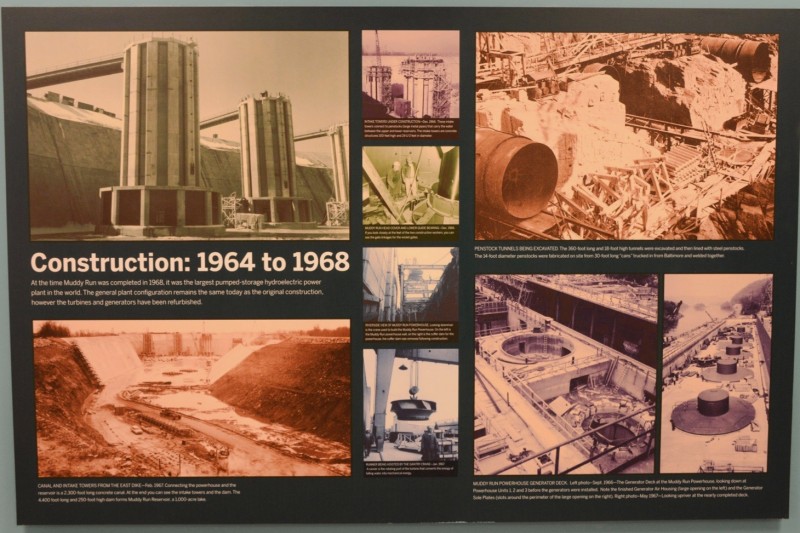

The Muddy Run Pumped Storage Facility is on the Susquehanna River, 40 miles north of Baltimore, and 60 miles west of Philadelphia. When it opened in 1968 it was the largest pumped storage plant in the world.

Muddy Run consists of a rambling 1,000-acre upper reservoir, and a power plant on the river, 400 feet below.

The reservoir has a lobe with a canal that brings water to four intakes above the plant.

The intake towers connect to four 25-foot diameter shafts that bifurcate underground to connect to the eight pump/turbines in the plant.

The plant is accessed by a service road that passes through a tunnel under a railroad track.

Each turbine in the plant generates 134 megawatts, giving the plant a total output capacity of 1,072 megawatts.

One of the runners, the spinning portion of the pump/turbine, is on display outside the plant.

The plant draws water from its lower reservoir, a dammed section of the Susquehanna formed by the Conowingo Dam, the last dam on the river before it enters Chesapeake Bay.

A few miles downstream is the Peach Bottom Nuclear Power Plant, one of the first commercial nuclear plants in the nation. Muddy Run was under construction when its first reactor went online in 1966, and two larger reactors opened in 1974.

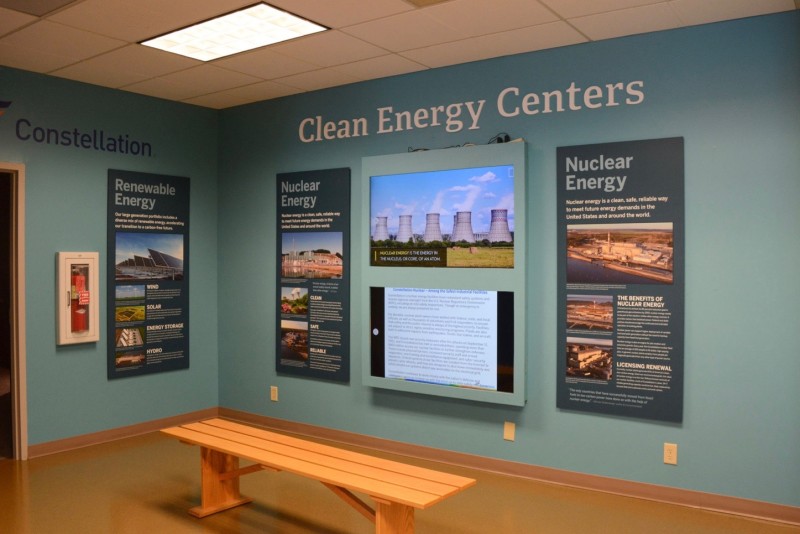

Some of the shore of the upper reservoir is a recreational park, operated by Constellation Energy, the utility which owns Muddy Run, and the Peach Bottom plant.

The company has a small visitor center in the park that provides information about the Muddy Run facility, and is a destination for school groups.

Constellation Energy is one of the largest power companies in the USA.

In addition to Muddy Run and Peach Bottom, Constellation Energy has around 24 gas and oil power plants.

It also has 14 nuclear power plants.

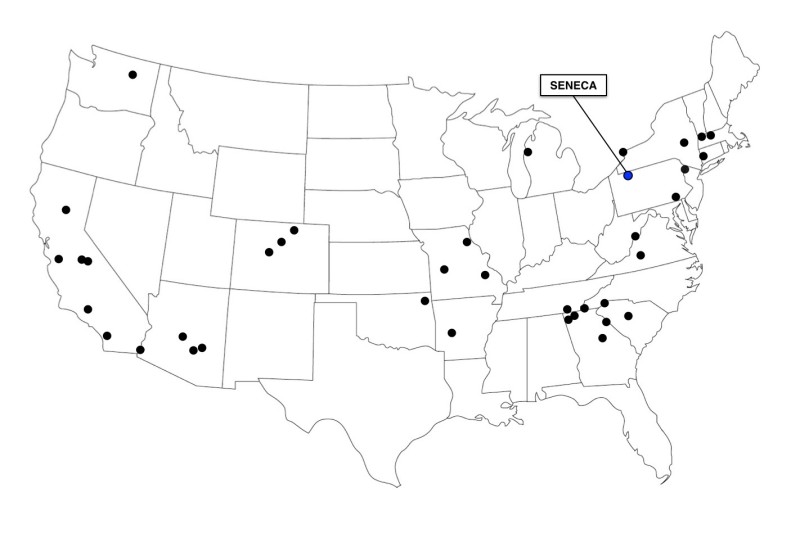

The Seneca Pumped Storage Station is located in northwestern Pennsylvania, along the Allegheny River. It opened in 1970, and generates 450 megawatts at its peak.

The circular upper reservoir is a half-mile wide, and rests 800 feet above the power station next to the river.

The plant was built next to the preexisting Kinzua Dam, a large flood control dam completed by the Army Corps of Engineers in the early 1960s.

The Kinzua Dam created a reservoir 24 miles long, flooding all the way back to the Seneca Indian Reservation in New York State.

The pumped storage plant is contained in a powerhouse below the dam, discharging into the river at the stilling basin at the bottom of the dam. Inside are two reversible pump/turbines, and a third non-reversible turbine.

Water enters the plant from an intake built onto the upstream side of the Kinzua Dam, entering the plant by a side pipe, separate from the main vertical penstock.

From there it is discharged directly into the river, or pumped 800 feet upwards to the upper reservoir, generally at night, when power demand–and cost–is lowest.

During the day, when demand for electricity increases, and its value goes up, the water flows out of the upper reservoir though the same vertical tunnels, to the power station.

The water then leaves the station and flows down the Allegheny River unobstructed, all the way to Pittsburgh, 195 miles downstream, where it joins the Monongahela, and becomes the Ohio River.

Before leaving the site, just past the power station, is the Big Bend Recreation Area, with overlooks to help see and appreciate the natural history of the area.

There is a visitor center, which is closed most of the time.

It is operated by the Army Corps of Engineers, with displays about flood control dams, reservoirs, and safe water-based recreation.

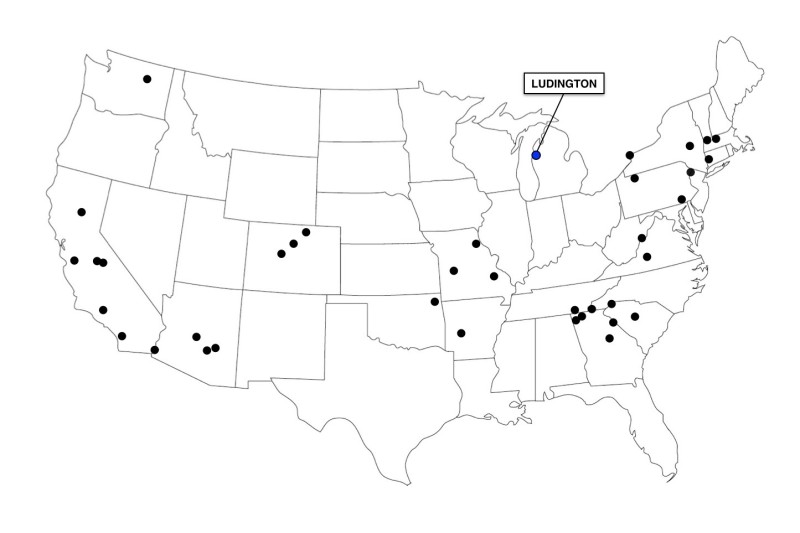

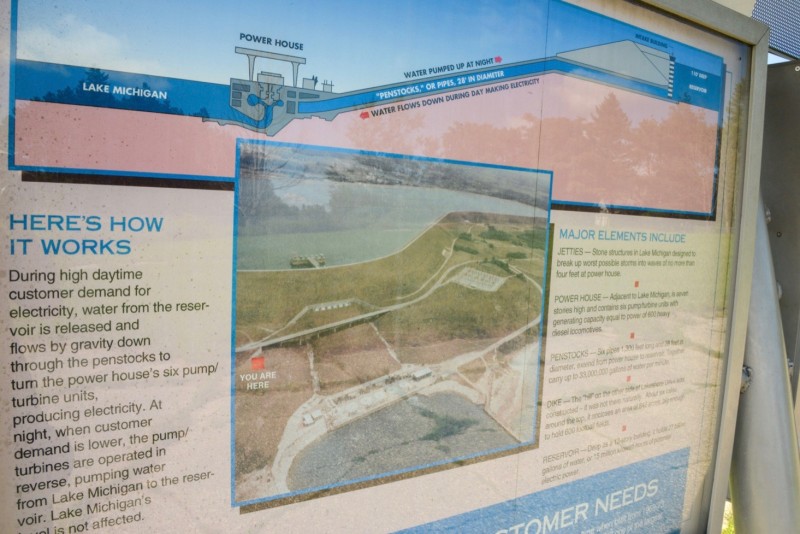

The Ludington Pumped Storage Plant is the second largest pumped storage plant in the USA. It is located in the town of Ludington, on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, which it uses as its lower reservoir.

Its upper reservoir was built on a bluff above the shore, and its shape was determined by minimizing the amount of earth moving required, based on the existing contours.

When Ludington opened in 1973, after four years of construction, it was the largest pumped storage plant in the world. It exists to stabilize the electrical grid in the Upper Midwest, which is heavily dependent on nuclear plants, five of which are along the shores of Lake Michigan.

Jointly owned by Consumer Energy and Detroit Energy, the plant has had recent upgrades that have increased its output. Its interpretive infrastructure has also been enhanced, and is robust.

A walkway takes the curious on a bridge over the shoreline roadway to the principal overlook, next to the power plant, where a battery of informational plaques and signage awaits.

The rugged yet airy main display has four panels, using cross-sectional diagrams, photos, and maps.

Each of the six reversible pump/turbines in the plant has the capacity of generating 387 megawatts, adding up to 2,322 megawatts total, enough to power a city of 1.6 million people. For a few hours, at least.

Six penstocks, each 1,300 feet long and 28 feet wide, are just beneath the surface of the 170 foot tall dike that forms the walls of the upper reservoir, and carry water between the upper reservoir and the powerhouse.

A sign explains how fish are kept out of the intakes with 2.5 miles of nets encircling the outfall/intake area, beyond the jetties that prevent waves from battering the plant.

Another sign explains that providing public access to the grounds around the plant for recreation is required by the federal permit to operate the plant, suggesting that reading their signage is a recreational activity.

A runner from one of six turbines in the plant is on display nearby. It was in use from the plant’s opening in 1973, to 2019, when the plant was overhauled.

It is nearly 30 feet in diameter, weighs 330 tons, and spun at 112 revolutions per minute.

Some of the re-contoured grounds next to the reservoir are used as a frisbee golf course.

A path heads up the northern edge of the reservoir.

The path leads to an overlook.

Inside is just one interpretive sign, giving some numbers to the body of water outside.

The upper reservoir is two miles long, 842 acres in size, 110 feet deep, and holds 25 billion gallons of water, 17 billion gallons of which are considered usable, causing a 67-foot change in water level in the reservoir.

Levels in Lake Michigan, 360 feet below, are unaffected.

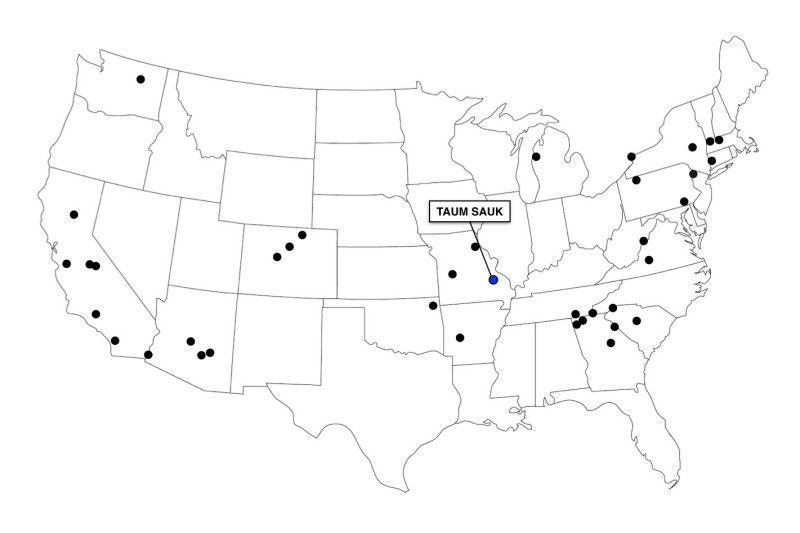

The Taum Sauk Pumped Storage Facility is a 450-megawatt project in the Ozarks of southeast Missouri.

The project has a 55-acre upper reservoir, connected by a tunnel to a power plant, located on the lower reservoir, on a dammed creek.

The facility opened in 1963, after three years of construction, and is owned and operated by Ameren, Missouri’s largest utility company.

The upper reservoir is unique, as it was created by building a 120-foot-tall continuous earth-fill dam.

It sits on a ridge of Proffit Mountain, five miles away from Taum Sauk Mountain, the highest point in the state, looking like a giant above ground pool.

The upper reservoir is 760 feet above the lower reservoir, which is a mile away. Water is pumped up and down to and from the lower reservoir, through a 7,000-foot-long underground tunnel, using two reversible pump/turbines in the powerhouse.

The water level of the lower reservoir fluctuates by as much as 15 feet, in a matter of a few hours.

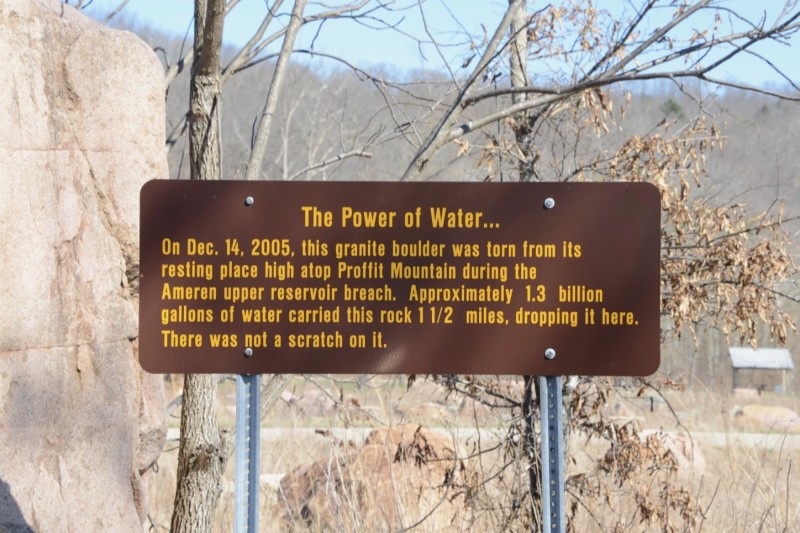

The unique design of the upper reservoir made it vulnerable, however. Ameren often kept the reservoir filled to the brim, sometimes just a foot or two from the top of the dam. Then, early on a December morning in 2005, the reservoir overflowed, and, without a spillway, its wall eroded and collapsed.

1.5 billion gallons of water spewed down the hill, scouring the ground of all trees and soil, down to bedrock. The water cascaded through Johnson’s Shut-Ins State Park, at the base of hill, then followed the creek bed back to the lower reservoir.

The dam at the lower reservoir held, and prevented the flood from reaching the town of Lesterville, where it likely would have done significant damage.

The superintendent of Johnson’s Shut-Ins State Park was at home with his wife and three children when the flood flowed through the park for 12 minutes, and washed their house away, but they all survived.

The mission of the park, however, was changed, to reflect its newly altered landscape.

The path of the flood coming down the hill is clearly visible in the park today, and visitors can walk up it to see the scour and the exposed bedrock.

The grounds are covered in boulders that came down with the flood,

creating a new and unusual attraction.

Some of the rocks are as big as a truck.

Ameren was declared liable for the accident, as operators knew the water level sensors were unreliable. They were fined $15 million by the federal government, and have paid more than $200 million in settlements.

In 2010 a rebuilt reservoir atop Proffit Mountain went online. Instead of an earth-filled dam, this one was made by the more sturdy roller compaction method, and includes a spillway. It cost $500 million, much of which was covered by insurance.

Evacuation sirens can be seen throughout the area, including in the town of Lesterville.

The Salina Pumped Storage Plant is in northeastern Oklahoma.

The plant is located at the dam between the upper reservoir, Lake Holly, and the lower reservoir, Lake Hudson.

It is owned and operated by the Grand River Dam Authority (GRDA), which operates the Kerr Dam, a large conventional hydro dam on the Grand River, which provides flood control and power for the region, and forms Lake Hudson. GRDA is the state’s largest electrical utility.

The pumped storage project dam is located in Chimney Rock Hollow, and is an earth and rock-fill dam, 185 feet high. Six penstocks run down the face of the dam, bringing water from the upper reservoir to the powerhouse’s six reversible pump/turbines at the base of the dam, which together generate a maximum of 260 megawatts.

Water enters and leaves the penstocks at the top of the dam, at the end of a channel leading from the upper reservoir.

The upper reservoir was originally called Chimney Rock Lake, but was later renamed Lake W. R. Holly, after an engineer on the project.

There are boat ramps on the lake.

Otherwise there is not much development or recreation on its shores.

Not much interpretive or explanatory signage either.

Just names and labels.

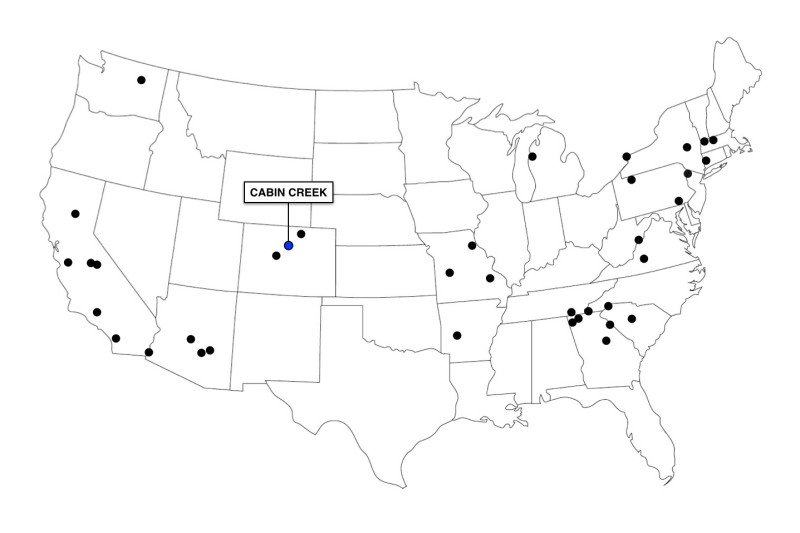

Cabin Creek is one of two major pumped storage projects in Colorado. It is located in a steep valley south of Georgetown, at an elevation of more than 10,000 feet.

Cabin Creek consists of similarly sized upper and lower reservoirs, separated by 1,192 feet of elevation, and a power plant on the shore of the lower reservoir.

Three interpretive plaques next to the lower reservoir briefly describe the operation.

Water goes up and down between the reservoirs through a 3/4-mile-long underground tunnel, and through two reversible pump turbines, capable of generating 324 megawatts between them.

The plant opened in 1967, and is owned by Xcel Energy, a large regional utility company that operates facilities in the Midwest and West, including a dozen coal-fired plants and two nuclear plants.

The plant might be best known for a tragic industrial accident in 2007. Workers were doing repairs inside the main tunnel, spraying epoxy sealant on the walls, when volatile solvents caught fire. With limited egress along the 4,125-foot-long underground tube, some workers were trapped inside. Five of them died.

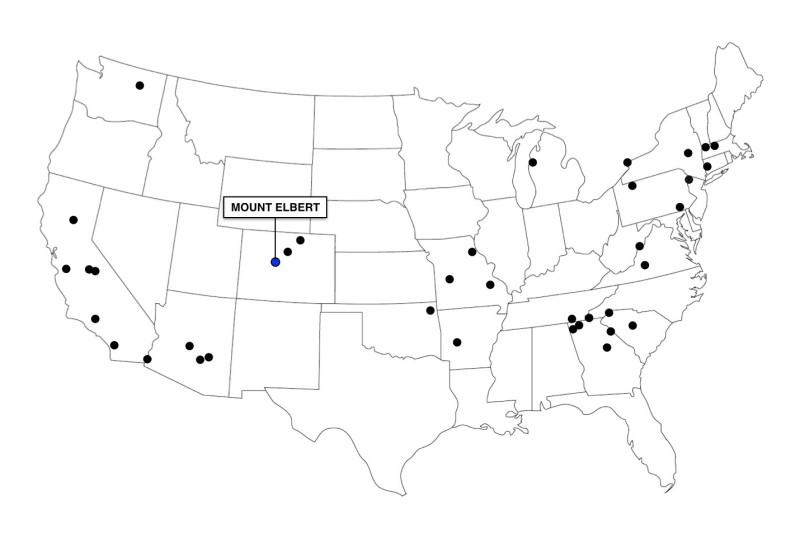

The Mount Elbert Pumped Storage project is located in central Colorado, and produces up to 200 megawatts of electricity.

It consists of a constructed upper reservoir and a powerhouse located on the lower reservoir, two connected lakes, aptly called Twin Lakes.

The project is named after Mount Elbert, the tallest mountain in Colorado, which looms above the plant.

The upper reservoir, known as the Mount Elbert Forebay, is 275 acres in size, and fluctuates as much as 31 feet between being drawn down and filled up.

The Mount Elbert Forebay also holds water from the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, a large-scale water capture and storage project, under construction from 1964 to 1981 by the Bureau of Reclamation, that uses a network of tunnels and reservoirs to bring water from one side of the Continental Divide to the other.

The Fryingpan-Arkansas Project water comes from a reservoir near Leadville, through the Mount Elbert Conduit, an 11-mile-long covered channel, that enters the Mount Elbert Forebay on its north side. It joins the pumped water already in the reservoir and exits through the intakes on the southern side.

The water flows from the intakes on the upper reservoir through two underground penstocks 15 feet in diameter, 3,000 feet down to the power plant, and out into the lower reservoir.

The power plant was built in 1974, but the two pump/turbine units came later, going online in 1981 and 1984. Each produces 100 megawatts.

Twin Lakes used to be two small ponds along Lake Creek, before the Twin Lakes Dam was built, which flooded the area to serve as a reservoir for the pumped storage project, and for other end users of the water, further down the Arkansas River Watershed.