A large statue of Vulcan, the Roman god of the forge, looms atop Red Mountain, a long hill that runs through Birmingham.

The statue was created for the World’s Fair in St. Louis in 1904, as a symbol for the city of Birmingham, celebrating its iron and steel industry.

Vulcan was moved here from the local fairgrounds in 1938, and the hilltop park was developed around him.

The 55-foot tall steel sculpture was placed on top of a 125-foot tall tower, and an elevator was added in 2004.

The park has a museum about Birmingham inside the Vulcan Center.

There are displays about the local steel industry.

As well as lots more about the Vulcan statue.

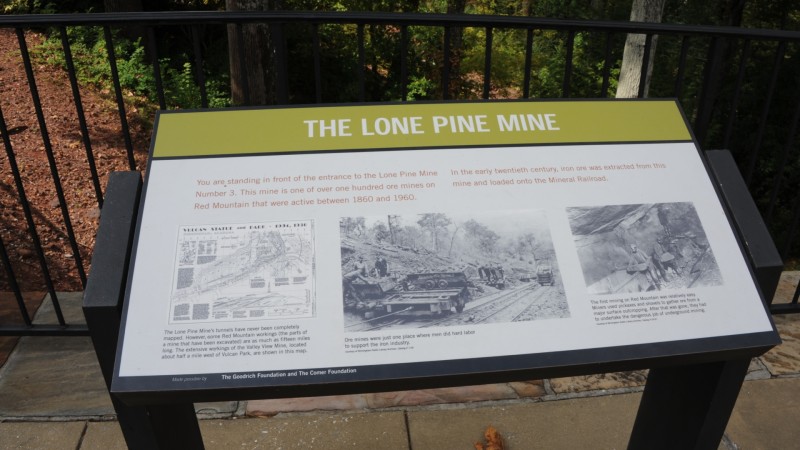

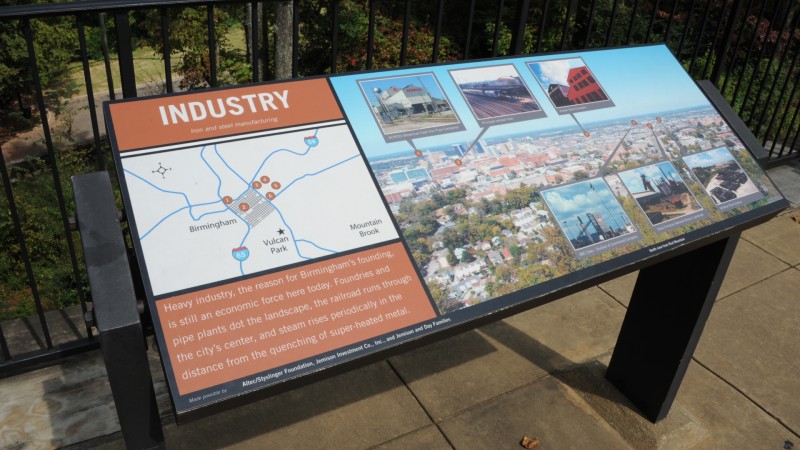

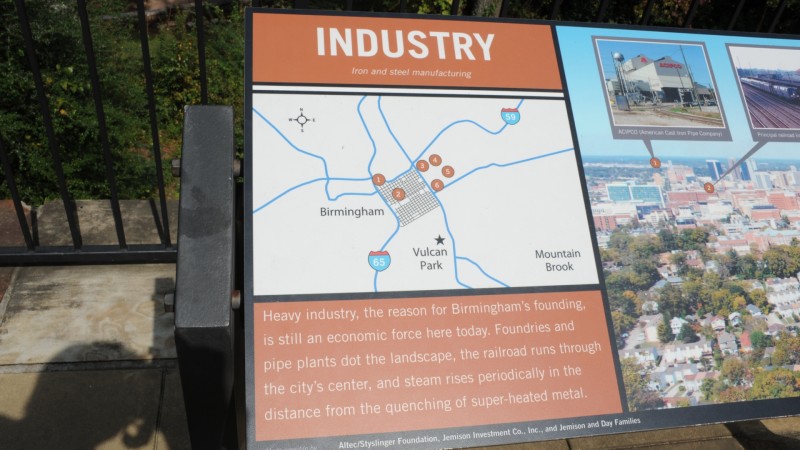

Outside, in the park around the base of the tower, interpretive signage describes the local terrain and its natural resources.

Plaques describe how Red Hill is pock-marked with hundreds of iron mines.

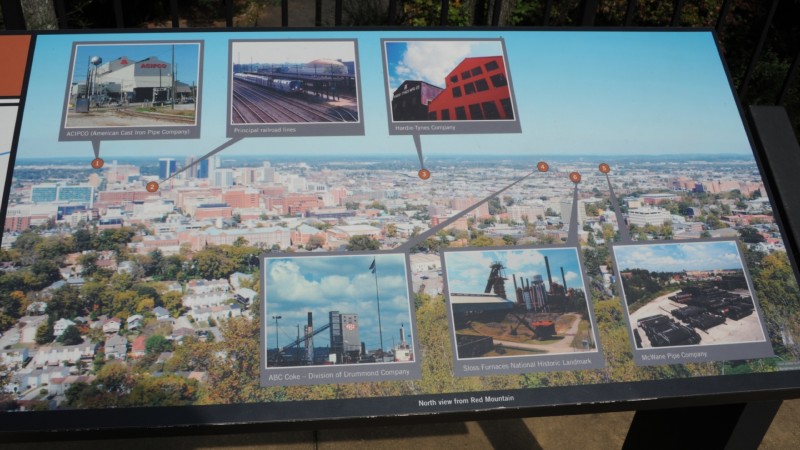

At an overlook, a plaque points out steel plants still working in the valley below.

A map on the ground is embedded with the location of these industries too.

Including the largest Old Steel site in the South, U.S. Steel’s Fairfield Works.

At the southern end of the valley, in the town of Bessemer, is the U.S. Pipe plant and its new ductile iron pipe mill.

McWane is another of the nation’s largest iron pipe companies, and has plants around Birmingham and other parts of the state.

The American Cast Iron Pipe Company started in Birmingham in 1905, and employs 2,000 people in this plant.

The only active Old Steel plant left in Birmingham though is U.S. Steel’s Fairfield Works.

The plant is the largest producer of new, raw steel in the southeastern United States.

It uses iron ore, taconite pellets, scrap metal, limestone, and coke to make two million tons of steel a year.

Fairfield Works has the largest blast furnace in the southern USA, making 6,000 tons of molten iron daily.

The plant uses a continuous slab caster and continuous rounds caster to make sheet steel and seamless pipe.

U.S. Steel bought the plant from Tennessee Coal and Iron in 1907.

It is one of six integrated steel mills still operated by U.S. Steel, the last of the big old American steel companies.

Walter Coke is one of two large coke works still operating in Birmingham.

The site was first developed in 1881 to produce coke for the Sloss furnaces, nearby.

120 coke ovens produce 420,000 tons per year for the local steel industry.

Coke is produced by baking coal. In steelmaking, when added to the furnace, it separates the oxides from iron ore, purifying the remaining iron.

Next to Walter Coke is an even larger coke plant, Alabama Byproducts Corporation (ABC), with 132 ovens, making 730,000 tons per year.

There are only a half dozen independent merchant coke plants left in the USA, and this is the largest one.

More often coke is manufactured as part of the integrated production of old steel plants, where all parts of production are concentrated in one place.

Non-functional remains of old steel and iron sites can be found around Birmingham, such as the Ensley Steel Works, established in 1889 by Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad.

Once a large plant employing more than 1,000 people, it has been abandoned since 1984, and is now overgrown.

Remains of another former plant can be found at the Wade Sand and Gravel site.

Though most of the site has been consumed by a gravel pit, some ruins of the plant are still there.

Iron production was started here by the Pioneer Company in 1888.

Founded by the Thomas family from Pennsylvania, the housing built for workers was done in a style more common in that state, and less suited to the hot climate of the South.

The company town was called Thomas, and the plant was known as the Thomas Works.

It was operated for several decades by Republic Steel, with as many as 1,800 employees at its peak.

The blast furnace closed in the 1970s, and operations ceased in the 1980s.

The excavation of limestone is still going on, and threatens to take over the 500-acre site.

Parts of the large coking plant, built in the 1950s, are still there.

Over the last 15 years, the owners have operated an informal artist residence program among the ruins.

Artistic embellishments can be found here and there.

Closer to downtown Birmingham, the Sloss Furnace occupies a small 17-acre area, but looms large in many respects.

This iron works dates back to 1881, was modernized in the 1930s, and shut down in 1971.

The last owner donated it to the state of Alabama for historical preservation. The state eventually donated it to the city of Birmingham, and it became a museum in 1983.

Though some of the plant was removed, two blast furnaces dating back to 1931 and a compressor building from 1902 remain, with their contents and appurtenances.

The surfaces of the boilers were cleaned and covered with a mastic, then painted in a rust tone that is repainted every 15 years.

These are the only blast furnaces in the nation that are fully (and officially) open to the public.

Visitors are permitted to wander all over on their own, even into crawl spaces and up old stairways.

Public events are held here, such as demonstrations of iron production, and concerts.

Every Halloween the site is turned into a creepy haunted house.