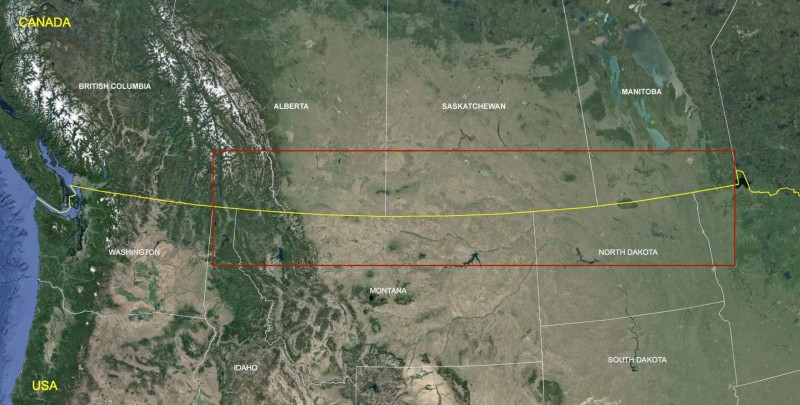

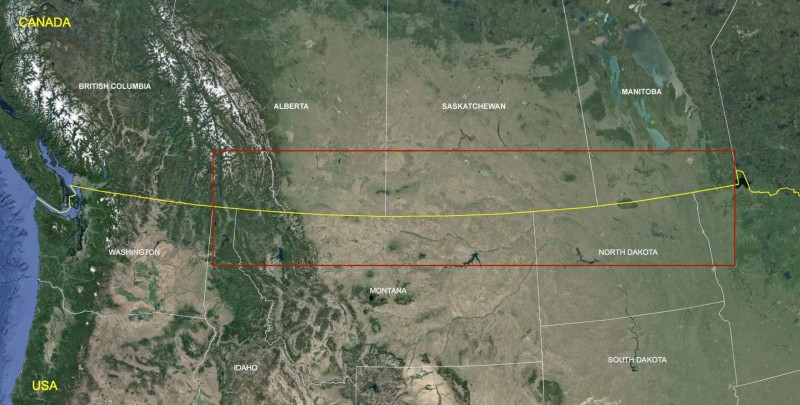

A Linear Portrait of the USA/Canada Border

The border follows the straight line of the 49th Parallel across the western part of the country for 1,200 miles, half the width of the continent. This boundary is straight and flat, until it gets to the Rockies, where few man-made structures cross the line. This part of the border was initially surveyed between 1872 and 1876, and was the last stretch of the boundary to be fixed along the contiguous United States. Though the 49th Parallel border could be the longest, straightest, physical line on earth, it is not perfectly straight, as it was based on surveying practices of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The accepted boundary, complete with its wanderings of up to a quarter mile from the true 49th, is now fixed, set in a thousand monuments of iron, aluminum-bronze, steel, or concrete, anchored along its path, no matter how mountainous, or monotonous.

From east to west, the 49th Parallel boundary begins in the waters of the Lake of the Woods, in Minnesota, three miles off Buffalo Point. This is where the line from the Northwest Angle comes due south, for 26 miles, and hits the 49th, forming a right angle.

From here, the 49th line heads west, and makes its first, brief, landfall on the southern edge of the peninsula, known as Elm Point.

There are a couple of seasonal cabins and trailers here, accessed by boat or over ice, but otherwise its unoccupied. It is a peninsula off a peninsula, another partial exclave of the USA, accessible only through Canada, or over the water. The line is delineated by the border cut-line through the trees.

Just west of it is another small peninsula, in the marsh.

Or two, or three, depending on how finely you want to split these hairs.

The 49th Parallel border makes landfall with the continental USA in a grassy bog on the west shore of the lake, and meets its first crossing a couple miles further west.

This is the Warroad/Sprague crossing on Highway 313, between western Minnesota and eastern Manitoba. This is the crossing that eventually leads to the roads into the Northwest Angle, and it is the Port of Entry that you might be communicating with at Jim’s Corner, on your return to Canada.

It is 18 miles west to the next border crossing, the Roseau/South Junction crossing, which has a new Port of Entry building and a shooting range on the USA side. The small Canadian Port of Entry is a half mile north of the boundary.

Ten miles west is the Pinecreek/Piney Crossing, on Highway 89, the least busy crossing in Minnesota, averaging less than 25 cars a day. It also has an airport with a runway that crosses the border, which is not very busy either.

Pilots landing here from the USA park at the ramp on the Canadian side, and call for an officer from the Canadian Port of Entry, next to the road, to come meet their plane. Landing from Canada, they park at the ramp on the US side, and do the same. Though it is operated by the Minnesota Department of Transportation, the northern end of the runway extends into Canada. This was done as it could not be extended southward without having to cross a road.

This is the only paved runway that crosses the International Boundary. Though it is one of six airports that straddle the line, the others are grass landing strips, or just have ramps that extend over the boundary.

Nearly 40 miles across fields, bogs, and woods is the next border crossing, Lancaster/Tolstoi, a lightly traveled crossing on Highway 59, with a new modernist USA Port of Entry building. This is the westernmost open border crossing in Minnesota.

Ten miles west is a pipeline crossing, surrounded by fields of large-scale farming. The pine trees and bogs of Minnesota finally give out, and the big agriculture of the Dakotas begins.

The last border crossing in Minnesota, Noyes, next to the town of Emerson, Manitoba, was closed in 2006, and the old brick Port of Entry on the USA side was still listed for sale, in 2014.

The Canadian Port of Entry was closed in 2003, and simply sits, empty.

For decades, Noyes was a substantial border crossing, due south of Winnipeg, less than 60 miles away. Crossing slowed after the construction of Interstate 29, just over the state line in North Dakota, and other improvements and expansions to the Port of Entry there. Without the border traffic, the small town on the USA side of the crossing is now isolated, its few businesses closed. This is the west end of the 547 miles of Minnesota’s boundary with Canada.

Next to Noyes is the Red River, which separates Minnesota from North Dakota, and the old crossing at Noyes from the new one at Pembina.

The river flows northward into Canada, and controlling its flow is an international issue, sometimes leading to conflict, since water management on the USA side can cause floods to occur in Canada. Winnipeg built a massive channel to route the river around the city, if necessary. In 2011, the town of Pembina was surrounded by flood water, like an island, and the raised bed of the Interstate was a dry line connecting the town to the Port of Entry, also built on raised ground, surrounded by levees.

Pembina is the busiest crossing in the state, with more than a million cars passing through here every year. There are 17 more crossings along the 310 miles of the rural border in North Dakota, and only two others that are open 24/7. Most of the crossings are along farm roads and small highways, crossing perpendicular to the boundary, with 15 or 20 miles between them. At several crossings, the road makes a curve or shifts diagonally on one side of the line or the other, since the Canadian Township and Range grid does not always line up with the American one.

The next crossing west of Pembina is the Neche/Gretna crossing, 15 miles away, which has a new USA Port of Entry building, and sees up to 300 vehicles a day, the fourth busiest crossing in North Dakota.

16 miles west is the Walhalla/Winkler Crossing, also with a new USA Port of Entry, and an average of 150 cars crossing per day.

Nearby is an abandoned underground launch control facility for the local missile silo field, shut down in the 1990s. This was part of a network of hundreds of intercontinental ballistic missiles that were operated by Grand Forks Air Force Base, 70 miles away. There are dozens of abandoned and still active missile sites in North Dakota, within a few miles of the boundary. This, after all, is the northern limit of the continental USA, closest to the routes missiles take between us and the Russians. Also, as it is the middle of the country, missiles can go east or west, if they need to. More importantly though, the middle of the continent it is away from the ocean, and furthest from a missile attack off our coasts, from ships or submarines, allowing more time to respond before the enemy strikes these vital missile fields.

Cavalier Air Force Station, 20 miles south of the Walhalla/Winker Crossing, has a large phased array radar pyramid that watches for missiles coming towards the US over the Canadian Arctic.

15 miles further is a former missile defense radar site, at Nekoma, with another ten-story tall concrete pyramid looming over the Prairie, no longer in use, and simply too big to be torn down.

The Maida/Windygates crossing, 20 miles west of Walhalla, also has a new US Port of Entry, and just a few dozen crossings on a busy day.

15 miles west, the Hannah/Snowflake Crossing is one of the slowest along the entire border, with just a few cars per day. It too has a new USA Port of Entry.

Conditions are similar at the Searles/Crystal City crossing, 11 miles west . . .

and at the Hansboro/Cartwright crossing, 19 miles west.

Nearly all of these lightly used crossings in North Dakota have been replaced since 2011, some of the more than 35 US Ports of Entry that were modernized with the $420 million given to the Department of Homeland Security for this purpose as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. There are three basic sizes, depending on traffic volume, and some variation in architectural style, though quite a few are identical. Costs ranged from $6-15 million. They are generally LEED certified institutional sheds with offices, stainless steel bathroom fixtures, bulletproof windows, and access corridors that buzz visitors in through hallways with locked doors on either end.

Also common are re-routed roads, feeding traffic through the new station, and leaving the original road abandoned and gated, sometimes with visible vestiges of where the old Port of Entry once stood.

The next crossing, St. John/Lena, 14 miles west of the previous crossing, is an exception.

The old brick USA Port of Entry at this remote and lightly used crossing was preserved for historic purposes.

Across the street from the Port of Entry is the Border Lounge. Alcohol, as well as gas, tends to be cheaper in the US, with less taxes attached to it. The bar used to be called The Bucket. Some locals called it “the bloody bucket” as there were so many fights there. The steak dinners there are reported to be worth the drive, for some.

The next crossing, 18 miles west, is Dunseith/Boissevain, and the International Peace Garden. The crossing is the second of the three crossings in North Dakota that are open 24/7. It is 45 miles north of Rugby, which is the “geographic center of the USA,” by some ways of measuring.

The Peace Garden, a park really, spans the boundary, west of the crossing, with 2,300 acres extending on either side. It opened in 1932, to celebrate the best of the shared physical, cultural, and political terrain of the two neighboring nations. Though you must check with customs and immigration when you depart, at whatever country you depart into, there is no need to stop to get into the park, and once inside, you can cross the boundary freely – that’s the whole point. It’s an international purgatory.

Beyond the looped drives with picnic areas, and vistas of rolling lawns, ponds, and woods, there are many unique features of the park, such as a carillion bell tower, a floral clock, the International Game Warden Museum, a 9/11 memorial park, auditoriums, a music school, and a new visitor center with a café, gift shop, and cactus garden. These, though, are asymmetrical features of the park.

The most remarkable aspect of the International Peace Garden is the way it is divided, in half, exactly along the international boundary, along the 49th Parallel.

The symmetry starts with the entry gates, which project from footings in either nation, and arch towards one another over the traffic island, without touching.

Then at the other end of the traffic island, at the entrance, the kairn, with a ball on top.

Past the entrance is the great lawn, with dual plaques commemorating good will and friendship between legislatures, and a view of the twin spires at the far end of the park, that draw you further in.

Along the way the boundary manifests itself in many linear forms, including as a series of pools, flower beds, and a perfectly straight stream, with small waterfalls.

At the west end of the gardens is the Peace Tower, a monumental concrete sculpture that looks like the Twin Towers from a distance, but was completed in 1983.

When seen from the side, it is clear that it is made up of two “V” shaped towers, funneling towards the center, representing the people of the four corners of the globe, coming together in the two neighboring nations.

In the shadow of the towers, further west down the 49th boundary, is a chapel, the only building in the Garden that is crossed by the line. It was opened in 1970, and is the nondenominational spiritual heart of the Garden.

Its interior and exterior is symmetrically split by the international boundary.

Even the organ is equally divided: the left arm arm of the organist would be playing from Canada, the right arm from the USA.

Outside the back of the chapel, still heading west through the park, is a great granite monument erected by the International Boundary Commission in 2003, commemorating more than a century of work to, as the monument says: “Maintain at all times an effective boundary line between the Dominion of Canada and the Unites States…and to determine the location of any point of the boundary line which may become necessary in the settlement of any questions that may arise between the two governments.”

Beyond that is the last boundary marker in the park, one of the more modern stainless steel obelisks, used since the 1980s to replace many of the damaged monuments along the line, as stainless steel is more resistant to bullets.

Beyond it the vista line heads through the adjacent woods, and the 49th Parallel boundary continues its linear derive across the western half of the continent.

Back out the front gates of the Garden, the real world feels much more asymmetrical, and things not quite so well balanced. Visitors leaving come immediately to a ‘T” intersection, and have to make a choice, to go left or right, north into Canada, or south into the USA, decidedly different directions.

Either way, a Port of Entry awaits, with customs and immigration officers eager to find out who you are, where you have been, where you are going, and why.

The International Peace Garden is in the Turtle Mountains, a hilly region surrounded by flat agricultural plains. Its border crossing is the only one in the hills, which are dotted with hundreds of small lakes and ponds.

One of the largest lakes, Lake Metigoshe, is a recreational lake, divided by the boundary, and thickly settled with homes along the shore. On the east side of the lake, part of a Canadian community hangs down south of the line, and at least one dock and a boat house are directly on the boundary.

On the western shore, a community on the US side is cut off from its counterpart on the Canadian side, and the road is now a cul-de-sac.

A narrow house has been built on the US shore, just barely outside the 10 foot vista line zone.

The line heads west through the Turtle Mountains for another eight miles, until the next border crossing.

Along the way, on the west edge of the mountains, a few miles south of the line, is a curious attraction called Mystical Horizons. Described as a 21st century Stonehenge, there are equinox columns, line-of-sight tubes, and other outdoor devices made to connect the world with the cosmos. It was conceived and built by Jack Olson, an aerospace engineer, inventor, and artist, who worked for Boeing for most of his career. He is also the author of book about his early life growing up in the Turtle Mountains, called In the Middle of Nowhere.

Looking west from Mystical Horizons, the view is from the last high ground for many miles. The border continues across the flat plains of western North Dakota.

The next crossing is Carbury/Goodlands, at the base of the Turtle Mountains, on Highway 14.

It has a new US Port of Entry building, identical to the one at Hannsboro, and a few other crossings in the state.

West of that the boundary passes through the Souris River, an engineered drainage channel that extends into Canada.

More than 35 miles from the previous crossing is the Westhope/Coulter Crossing, on Highway 83. The new US Port of Entry building is identical to the previous one.

Also like several other crossings in the state, the original roadway, where the old Port of Entry stood, is closed off, stranding a square prefab building, an already abandoned duty free store.

The Antler/Lyleton Crossing is 12 miles further west. Three miles past it the land on the Canadian side changes from Manitoba to Saskatchewan.

12 miles further is the Sherwood/Carievale crossing, surrounded by pump jacks. The western half of North Dakota is well known for its fossil fuel boom, and the border through the region passes through gas and oil fields on both sides of line.

Another 29 miles to the next crossing. The highway between them passes by the L4 missile silo, one of 50 in a 50 mile-wide missile field here, operated out of Minot Air Force Base, each with a Minuteman III ICBM, ready to go. This field is one of three that surround Minot Air Force Base, and one of nine that exist in the USA. This field is the furthest north of all of them, and has around 25 silos within 20 miles of the border, and some less than 3 miles from the border.

The Northgate crossing is another low volume crossing, with a new US Port of Entry.

The new crossing was made on an existing road that was upgraded, diverting the traffic away from the small community of Northgate, a few hundred yards east.

The old Port of Entry was used as a private home for a while, but is now empty, and the old railway crossing is now out of service.

The next open crossing on the line is the Portal/North Portal crossing 12 miles west, in the middle of the split community of Portal, North Dakota, and North Portal, Saskatchewan. This is the second busiest crossing in the state, and when a new US Port of Entry was mandated, it was squeezed in sideways, to avoid taking up too much of the existing town.

The result is a dense and chaotic crossing.

It is 20 miles to the next crossing, on Highway 40, south of the dug-up coal mining town of Estevan, Saskatchewan, with two large coal-fired power plants.

The Noonan/Estevan Crossing itself is lightly traveled, as the bigger highway goes through Portal.

The crossing has a new US Port of Entry building, of the same neo-modernist LEED metal shed variety as the others.

21 miles west to the Ambrose/Torquay Crossing, which is open only during the day, like many of the crossings in North Dakota. This is among the least frequently used crossings along the entire boundary.

This crossing is one of only two on the North Dakota line that still has the old brick style US Port of Entry building.

15 miles west is the Fortuna/Oungre crossing on Highway 85, the last (westernmost) crossing in North Dakota.

The US Port of Entry is a new gray shed style, like the Noonan Crossing, and others.

On the road to the crossing is more extractive activity for the Bakken shale gas boom, centered in western North Dakota, mostly a little further south.

On a bluff a few miles south of the border is the ruins of the Fortuna Air Force Station, an old radar facility.

Another few miles west is Montana.

On the International Boundary, North Dakota turns into Montana next to a pond. Though remote and unvisited, this political “tripoint” is marked with a monument.

With 545 miles along the 49th Parallel, Montana has the longest stretch of the straight border. But with only 13 open crossing points, averaging out to one every 42 miles, it is the least crossed.

The boundary along most of the state goes between large-scale, dry wheat farms and massive cattle ranches, on both sides of the line. Sometimes their roads and fences wander over the line a little bit, without anyone seeming to care.

A few salt lakes span the boundary, and in one, called Salt Lake, 12 miles down the line from North Dakota, an island got clipped by the line, making another US quasi-exclave, like others in Minnesota, and Vermont.

Its nearly 25 miles into the state before the first border crossing, the Raymond/Redgway crossing on Highway 16, with a new modern US Port of Entry.

25 miles further west is the Whitetail/Big Beaver crossing, which was one of the least used crossings on the entire border, so it was closed.

The Canadian Port of Entry was demolished after it was closed in 2011, and the road has since been barricaded, a few feet inside the US.

The US Port of Entry was closed in 2013, but is still there, frozen in time, with the radiation detectors and other monitoring equipment removed.

Even the remote video kiosk, once used for after hours crossings by pre-approved locals with a card, is still there.

There were plans to build a new “post-9/11” style Port of Entry here, like at most of the other crossing in the region. The grading of the grounds had started already, before the decision to close it was made.

The closure of the crossing has had an effect on the Whitetail community along the road, though how much is hard to say, as it was already suffering.

The Scobey/Coronach Crossing, 11 miles down the line, is also lightly used, seeing less than 25 cars a day in the summer, and much less in the winter.

It got a new post-9/11 crossing, as part of the 2009 federal stimulus funds.

Spanning the border east of the road is a grass landing strip, running along the 49th Parallel for 2/3 of a mile.

This is an official airport, jointly owned by the US and Canada, and one of six airports that span the border line. It was built in 1955 by the Montana Pilots Association, to serve local ranchers, on both sides of the line.

Westward, the International Boundary continues across the fields for 44 miles.

To the next crossing of the line, known as Opheim/West Poplar River, which usually ranks in the ten least busy crossings on the whole border. It is so remote, that the border officials live in housing next to their respective Ports of Entry.

Another gas line crosses the boundary to the west, with a pumping station on the Canadian side.

It is 66 miles from Opheim/West Poplar River to the next crossing, the Morgan/Monchy crossing, on highway 191. It is ranked generally as the 12th slowest crossing on the border.

25 miles west, the Turner/Climax Crossing also is remote enough to have government housing for the agents working the station.

This is another one of the few joint facilities, where both Ports of Entry are contained in one building, and the building is directly split by the boundary.

With inspection lanes on either side, the building has the inverted symmetry of a yin/yang symbol, and red and white paint on the Canadian side, and red, white, and blue paint on the US side.

Westward, across the badlands, cattle fences and paths often cross the line.

The Willow Creek crossing, on highway 233, more than 60 miles west of the previous crossing, is usually ranked among the top 5 slowest ports on the border.

22 miles west, the Wild Horse crossing is also very quiet, closed at night, has some housing for workers, and a new LEED-type Port of Entry building.

Many of these remote crossings have camera sensors on the roads a few miles away, which sounds a bell in the station when a car passes by, alerting them that someone is on their way.

The badlands of the Milk River channel meanders across the boundary, a couple of times, with chaotic cattle fencing and paths. The Canadian side is now Alberta, though on the US side Montana continues.

The Whitlash/Aden crossing, on highway 217, 45 miles from the previous crossing, is often ranked as the second slowest on the boundary, with less than 1,000 crossings per year.

The Sweetgrass/Coutts crossing, 32 miles west of Whitlash, is the busiest crossing in Montana. Southbound is Interstate 15, which runs to Salt Lake City and Los Angeles, and northbound, Highway 2 goes to Lethbridge and Calgary.

The boundary separates the town of Sweetgrass, Montana, and Coutts, Alberta. The few homes that used to straddle the line disappeared long ago, and the line is now an open, unfenced space. A few back yards and a baseball field back on to this space, and the Boundary Commission has installed some extra monuments to make the line more apparent, as recently as 2014.

Camera towers watch the line closely.

At the west end of town is a shared airstrip, directly on the border.

On the east side of town, the international boundary runs along the north side of Border Road, where two Canadian farmsteads, a few miles away, can only be reached from this US road.

There is also an unattended dirt road crossing, with signs warning crossers to report at Sweetgrass/Coutts Port of Entry.

The boundary then crosses some train tracks, southward to the grain depot at Sweetgrass, and northward into Canada.

A large brick building west of the tracks is the old US Port of Entry, now privately owned, and used for freight handling and storage. Next to that the highway and the looming new Port of Entry building, which is shared by both countries.

The large joint Port of Entry building was built by the US in 2004. It is one of the few joint Port of Entry buildings, a structure shared by both countries, though their spaces are distinctly divided within it. A dominant architectural feature is a corridor that runs through the structure along the boundary line like a rectilinear tube, with a glass wall on either end. The west end of the corridor serves as the main staff entrance, next to employee parking lots on either side of the line, with two doors, one from Canada, and one from the US. Entering through either door leads down the hallway, divided on the line by a wall of steel mesh. The corridor tube travels over the southbound lane of the Port, as a skybridge, then doors and corridors lead off it, and down stairs to street level, into the separate halves of the building, on either side of the line.

It is 37 miles across rangeland and dry wheat farms, past a gas line and electric line crossing, to the Del Bonita crossing, down the line from Sweetgrass.

This is a lightly traveled crossing, with a new-style US Port of Entry, and some housing for the border officers.

It also has an airport, with a grass landing strip directly on the line. Some of these line-straddling airports were used in the early years of World War Two, before the US got involved (officially) but the Canadians had. Aircraft from the US were flown to these line airports, usually at night, where Canadian pilots picked them up, taking them into combat to fight the Germans in Europe.

Del Bonita is one of two international crossings on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, as the boundary is now tracing the reservation’s northern edge, for 50 miles. The International Boundary Commission has no jurisdiction on the reservation, as the treaty with the Blackfeet predates the treaty that established the IBC. The Blackfeet do cooperate with IBC though, and allow them to install monuments on the line.

There are around 16,500 tribal members in the reservation, and 69% unemployment.

In the middle of the reservation is the site of Lewis and Clark’s Camp Disappointment. This was the northernmost point on their 1804-1806 expedition to map and explore the lands just acquired through the Louisiana Purchase. Meriweather Lewis split off from the group camped at the Missouri River, and came here in the hopes that the headwaters of the Marais River would be found to be north of the 49th Parallel, thus greatly expanding the territory gained by the Louisiana Purchase. He discovered that this was not the case, however, and, disappointed, camped here.

A monument near Camp Disappointment was erected on a nearby hill by the great Northern Railway Company in 1925.

The Piegan/Carway crossing is 27 miles west down the line from the Del Bonita crossing.

It is the third busiest crossing in Montana, on a highway connecting Calgary to Glacier National Park.

There is government housing for the workers of the US Port of Entry, with twenty houses.

The old US Port of Entry, built in a log cabin-style to reflect the rustic mountains to the west, has been preserved for historic purposes.

The Rocky Mountains are ahead, westward on the line. The straight line of the 49th Parallel is about to get bumpy.

On the way, another gas line crosses the international boundary.

The Chief Mountain Crossing is the first truly mountainous crossing on the 49th Parallel, and it is closed in the winter months, usually for more than half the year.

The US Port of Entry is in a park-style building, suitable as the crossing is inside Glacier National Park.

At the crossing the boundary line is marked on either side of Highway 17 with the usual concrete posts used at crossing points by the IBC, and gates that are closed in off season. Looking west, the cut line is visible heading into the high peaks of the park.

Glacier Park is also known as Waterton–Glacier International Peace Park, especially near the border. The name was given to it in 1932, to celebrate the border-sharing national parks of Waterton Lakes, in Canada, and Glacier, in the US. At most other entry points in the US, signs call it simply Glacier National Park.

The border runs through the park for 40 miles, crossing the Continental Divide halfway through.

The Going to the Sun Road snakes through the mountains south of the border, and is the only road through the park.

Upper Waterton Lake spans the border, and is accessed by road from the north, at Waterton Park, a Canadian settlement on the shore. From the US the lake is only accessible by foot trails. Hikers crossing the boundary are supposed to check in with customs and immigration before leaving the park.

Just outside the park’s western road entrance is a dirt road north that follows the North Fork of the Flathead River for 45 miles, up to the border, where the road is gated at the Flathead/Trail Creek crossing, which closed in 1996, following flooding damage to the road north. The former Ports of Entry buildings on either side are unused, and in disrepair.

It is 63 miles west on the line from the previous official crossing at Chief Mountain, to the next, the Roosville/Grasmere crossing. This is the second longest uncrossed stretch on the 49th Parallel border.

The crossing is on US Highway 93, which continues south, all the way to Arizona. This is the second busiest crossing in Montana, and the last one in the state, heading west.

Westward, over the hills, is Lake Koocanusa, which is divided by the line.

The lake is 90 miles long, and extends 42 miles into Canada. It was created in 1975, by flooding the Kootenai River valley with the Libby Dam. The name Koocanusa was invented for the man-made lake, and is a combination of Kootenai, Canada, and USA.

The dam and reservoir is part of the Columbia River drainage, which is the most dammed major river system in the US. The 600 megawatts of electricity produced by the dam is managed by the Bonneville Power Administration, which provides electricity to cities as far away as Los Angeles.

The international boundary intersects the top of the state line between Montana and Idaho in a wooded area 40 miles west of Lake Koocanusa.

Idaho has 45 miles of the international border, with two crossings.

The Eastport/Kingsgate crossing is more than 50 miles west of the last crossing at Roosville, Montana. It is located on US Highway 95, which goes south all the way to the Mexican border, past Yuma, Arizona. It is a mountainous crossing, but is still fairly busy with truck traffic, connecting British Columbia to the US Interstate system, at I-90, a hundred miles south.

The border comes out of the mountains from the east, over the Moyie River, and hits the pavement at the crossing. One lane of Highway 95 goes north, and another goes south, through their respective Ports of Entry. There are a few businesses and homes in the small community of Eastport, on the US side, and a large truck to rail freight yard on the west side of town, next to a major pipeline crossing, with a pump station on the Canadian side.

The boundary continues westward, over the tracks, with an old railway water tank, and up the cut line to the next crossing on the line.

The second crossing in Idaho is less than 15 miles west down the line, the Porthill/Rykerts crossing on Highway 1, at the town of Porthill, on the east bank of the Kootenai River.

The river meanders back into Canada here, after coming out from under the Libby Dam, 80 miles upstream.

The current USA Port of Entry is a modest and modern building.

There is an old Port of Entry, just up the hill behind it, abandoned. It was replaced when Route 1 was straightened out, cutting off the loop through the east side of Porthill.

The old road passed by the brick housing that was used by the customs officials. The boundary line runs directly behind the homes, through their fenced back yards, in fact.

West of the Port, the line continues through the grassy parking area for the local airport, where pilots can park their planes and walk up the steps to report in. There is a row of concrete slabs, set in the grass of the parking apron, indicating the border line.

Across the aircraft parking area, the border heads due west, along the 49th Parallel, into the mountains.

It crosses the state line between Idaho and Washington in a thickly forested area, 24 miles further west. From there the border continues its journey west to the Pacific Ocean, across the top of the great and last state of Washington.

CONTINUE ALONG THE BORDER FROM EAST TO WEST

CHAPTER 6: WASHINGTON STATE